Nov 10, 2024

Can India’s 30-Year-Old IT Backbone Build a Global AI Powerhouse?

Deep Tech

Technology

Google's recent report reveals that AI could unlock $400 billion in economic value for India by 2030.

Genesis of a Tech Nation

In 1954, Prime Minister Nehru tasked P.C. Mahalanobis, founder of the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), with drafting the second Five-Year Plan.

This plan emphasised data collection and computation, leading to the establishment of ISI’s electronic computation laboratory. The journey of India’s IT industry began not in the 1980s but here.

By 1955, Mahalanobis had imported India’s first digital computer, the HEC-2M, from England for Rs. 2 lakh (around Rs. 2 crore today). This pioneering step laid the foundation for computational progress.

Around the same time, in Mumbai, Homi Jehangir Bhabha led efforts at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR).

By 1960, TIFR had developed its computer, the TIFRAC, which Prime Minister Nehru inaugurated in 1962. This marked India’s first significant in-house computational achievement.

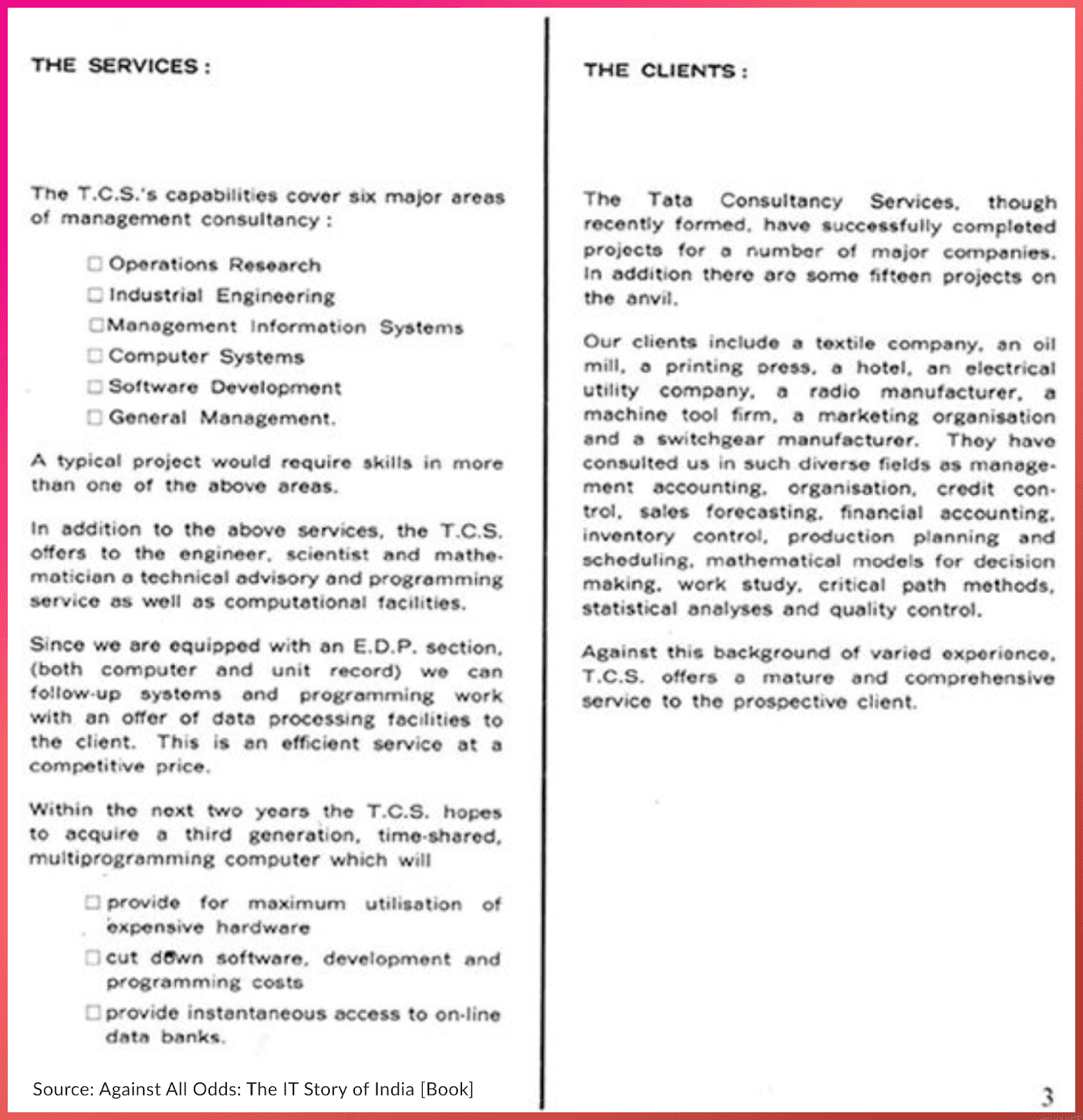

The 1960s also saw the birth of corporate computer services.

Lalit Kanodia, a tech-savvy IIT Bombay graduate and MIT researcher, advised Tata Sons to set up a data processing centre.

In 1967, the Tata Computer Centre was born and became Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) in 1968, under the leadership of F.C. Kohli. Initially, TCS computerised Tata companies and other Indian firms, but scaling up was tough. Committees in the early 1970s, wary of job losses due to automation, enforced strict controls on computer use, slowing industry growth.

A pivotal shift came in 1979 with the Sondhi Committee recommendations, which loosened restrictions on electronics imports and encouraged software exports.

TCS leveraged a 1974 scheme allowing imports tied to software exports to bring in a Burroughs mainframe. By the 1980s, TCS was tackling large-scale projects and even invested in an IBM 3090, a bold move considering its asset value exceeded TCS’s entire gross block.

Meanwhile, HCL, founded in 1976, pivoted from hardware to software when its American subsidiary’s strong support services surprised customers. Realising the potential, HCL shifted its U.S. focus to software services.

Wipro also emerged during this era. Led by Azim Premji, who had diversified from vanaspati and soaps to tech in 1976, Wipro set up Wipro Information Technology in 1980, entering the minicomputer manufacturing space.

These strategic moves, alongside policies like the 1980 DoE Manpower Committee recommendations, which expanded computer science programs and launched the MCA degree, set the stage for the following growth.

By the late 1980s, TCS had executed groundbreaking projects like SEGA’s real-time Swiss financial settlement system.

Another small company would be born, the truest form of startup in an era when starting a company was near impossible. Murthy’s journey—from managing IIM Ahmedabad’s computer centre to gaining valuable international experience in France—fueled his conviction that entrepreneurship was the path to creating jobs and lifting society out of poverty.

After leading the software division at Patni Computer Systems (PCS), Murthy gathered an exceptional team of programmers, including Nandan Nilekani, Kris Gopalakrishnan, S.D. Shibulal and others to start Infosys with just $250 in capital.

While the Indian entrepreneurs were building this new service, British-Canadian scientist Geoffrey Hinton released a paper in 1986. It would create the backpropagation algorithm to train neural networks. While the Indian entrepreneurs were setting the foundations for IT, miles away, the foundations of AI would be created.

By the late 1980s, India’s IT sector, with companies like TCS, Infosys, HCL, and Wipro, was ready for the boom that the 1990s economic liberalisation would unleash.

Data Gold Rush

The next decade marked a turning point for India’s IT industry, when ambition and innovation began reshaping its economic landscape.

Industry associations emerged to support and organise the growing sector as new companies emerged. The Manufacturers Association for Information Technology (MAIT) was formed in the early 1980s, bringing together computer manufacturers.

By the late 1980s, software companies found competing with the dominant hardware players challenging. They established NASSCOM to amplify their voices and secure their place in the industry.

Then, there was a phase of growth enabled by multiple factors.

First, the establishment of tech parks was a game-changer. Inspired by the success of the Kandla Free Trade Zone, the government launched Software Technology Parks of India (STPI) in 1991. These parks provided essential infrastructure and relaxed customs regulations, enabling software companies to focus on exports without the usual bureaucratic hurdles. By the late 1990s, STPI-supported firms thrived, contributing significantly to India’s IT export boom.

Talent management was another crucial factor.

Companies like Infosys excelled in recruiting and training top engineers. Infosys introduced Employee Stock Option Plans (ESOPs) and developed rigorous training programs. N.S. Raghavan at Infosys implemented selective hiring and intensive training, transforming fresh graduates into skilled software professionals in just a few months. This focus on nurturing talent ensured that Indian IT firms could meet the high standards demanded by global clients.

The innovative Global Delivery Model (GDM) also played a pivotal role.

Pioneered by leaders like Murthy and Nandan Nilekani, GDM allowed Indian companies to handle most software development remotely while maintaining close client collaboration. This model not only reduced costs but also ensured high-quality deliverables. By 1996, Indian IT exports had soared to over $1 billion, and by 1999, they reached $4 billion, showcasing the effectiveness of GDM.

Scaling sales and marketing efforts was equally important.

Indian IT firms established offices in the US and Europe, focusing on building strong relationships with Fortune 500 companies. They emphasised repeat business and word-of-mouth referrals, which helped them secure a solid global presence. By the late 1990s, companies like Cognizant and Mindtree emerged, riding the wave of strategic international expansion.

The Y2K crisis in the late 1990s became a massive boost for the Indian IT industry.

As the year 2000 approached, global companies desperately needed to fix potential computer glitches. Indian firms like TCS and Infosys were perfectly positioned to undertake these large-scale remediation projects.

TCS alone earned over $1 billion in exports by the late 1990s, and overall, Indian IT services garnered an astonishing $2.3 billion from Y2K efforts. This solidified India’s reputation as a reliable tech powerhouse and opened doors for long-term partnerships with global clients.

By the end of the 2000s, India had transformed from a budding IT hub to a global leader in software services and analytics.

Birth of Analytics Powerhouses

The turn of the century would witness the rise of Web 2.0, the user-generated web.

With the scale of UGC, platforms like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter became mainstream. Massive volumes of data would be generated through videos, images, and posts. Content would now be provided not by service providers but by users of these services.

In just a year of its launch, Facebook would command a user base of 5.5 million - users who would upload and share their photos and data with friends.

YouTube, too, saw a meteoric rise in its user base within a year of its launch, going from 30,000 daily active users a month after its launch to 20 million daily active users by the end of the year.

Companies would now have access to vast amounts of unstructured data, which would bring its own set of challenges and opportunities.

To combat this problem, the Apache Software Foundation created an open-source framework, Hadoop, in 2006. It was based on a white paper written by Google a few years ago and enabled the distributed processing of large data sets across a cluster of computers.

Hadoop would see almost immediately widespread adoption and pave the way for big data processing.

The decade also saw the birth of multiple analytical firms that realised the potential of harnessing this data for decision-making and growth. Fractal Analytics was founded in Mumbai in 2002 when Data analysis was still in its infancy.

The founders would recognise the potential of analytics and AI long before it went mainstream and were poised to take full advantage of the unfolding situation.

Having struggled for funding during the initial years as VCs and investors flocked towards software development and IT services, the founders would bootstrap their business and build their reputation through small projects.

Fractal secured contracts with major retail and consumer goods clients as data analytics went global. Their dedication to delivering high-quality insights powered by data and a customer-centric approach led to great positive word-of-mouth that helped scale their operations.

In 2004, Dhiraj Rajaram, a former strategy consultant, having seen first-hand how companies struggled with a disjointed approach to data analytics, would start Mu Sigma as a solution to bridge the gaps and promote better business outcomes.

Having faced resistance from companies unwilling to outsource their analytics and unaware of the added advantages of a cohesive data strategy, he would begin to formulate a value proposition that would gradually prove its worth.

Mu Sigma would position itself not as another service provider but as a strategic partner embedding itself within the company’s operations to optimise decision-making.

He would find a massive clientele in the financial, pharmaceutical and retail sectors, where businesses were eager to utilise advanced analytics to stay ahead of the competition. These two would be pioneers of data analytics and science, as the two would become massive soon.

Both firms gradually opened offices worldwide, including New York, London, and Singapore, as they aimed to grow and better serve their international clientele.

At the end of the decade, the world’s servers will process 9.5 zettabytes of data, equivalent to 12 gigabytes of information per person per day.

The Big Data revolution was truly here to stay, and India was already having its say.

Riding the AI Wave

The early 2010s would mark the peak of what was being called “The Big Data Revolution”.

2012 would see massive breakthroughs in deep learning with the introduction of AlexNet.

A convolutional neural network (CNN) created at the University of Toronto would dramatically outperform all existing techniques in image classification, spurring a sudden surge of interest in neural networks. It introduced the concept of utilising GPUs for faster computation and established new benchmarks for accuracy and efficiency in computer vision.

A few years later, Google Brain introduced TensorFlow, an open-source library to simplify the development of ML models. Due to its flexibility and scalability, it would see widespread adoption and enable engineers to build complex systems without bothering about the low-level details.

TensorFlow would be key in democratising machine learning by making powerful tools easily accessible. It would accelerate AI development and innovation in various fields, from NLP to healthcare. Big tech companies were ready to leverage AI as it went mainstream based on significant developments.

Microsoft would set up its R&D centre in Bengaluru, focusing on AI solutions tailored to the Indian market. The centre would also help India's linguistic diversity and build predictive tools for farming to improve crop yields.

Google would also set up an AI research lab in Bengaluru to focus on flood prediction and improvements in public health as it promoted its strategy of integrating AI into everyday life.

To avoid being left behind, Indian giants like TCS and Infosys will also increase their focus on AI to enhance their services and remain competitive globally.

India’s startup ecosystem would also flourish, with companies using innovative techniques to harness AI.

In 2013, Haptik positioned itself as a leader in conversational AI by using chatbots for customer service. This would allow businesses to provide 24/7 support, handle multiple customer queries at a time, and improve overall response times. By 2014, India’s startup ecosystem in general, was beginning to pick up.

To prepare for AI's emergence, India’s premier institutions, like the IITs and IISc, will introduce specialised courses and programs in Data Science, Machine Learning, and AI. These programs will include theoretical knowledge and practical training to ensure students can contribute to the ever-evolving workforce.

By 2015, companies like Microsoft and IBM would also collaborate with these universities to provide workshops to bridge the gap between academic knowledge and real-world applications.

India was surfing on the earliest wave of AI as explosive development was quietly about to happen.

Turning Challenges into Opportunities

Starting 2015, the world witnessed significant achievements in AI

IT consulting giant Infosys was part of a $1 billion donation to an unknown, not-for-profit group in 2015. The donation occurred during Vishal Sikka's time as Infosys's CEO. Sikka, a strong advocate for AI, played a significant role in facilitating the donation to the freshly minted AI company and acted as an advisor.

The not-for-profit group was called OpenAI.

AlphaGo's historic victory over the world champion Go player was the most notable. This event underscored AI's potential to tackle complex problems and inspired nations, including India, to explore its applications across various sectors.

This pace of progress would continue in 2017 and see one of the most significant contributions to AI.

Ashish Vaswani, a researcher at Google Brain, released a paper called "Attention Is All You Need." It introduced the Transformer model, which better enables neural networks to process data sequences at once. The aim is to improve training efficiency and better handle context in sequences.

The Transformer model facilitated breakthroughs in multiple key fields, from text summarisation to question-answer systems and what would later be introduced as conversational AI. It led to a new AI model called GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), which would become foundational in any NLP application.

It also marked a pivotal phase in India's journey toward leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) for socio-economic development. During this period, India faced numerous challenges, including a vast population with diverse needs and varying levels of access to technology. Recognising the need for a comprehensive digital infrastructure, India expanded its Aadhaar program, creating the world's most extensive biometric ID system.

By 2017, the Digital India initiative aimed to transform India into a digitally empowered society and knowledge economy. This ambitious program focused on improving digital infrastructure, enhancing internet connectivity, and promoting digital literacy nationwide.

Healthcare startups like SigTuple automated medical data analysis using AI to improve diagnostics in pathology and ophthalmology. Using thermal imaging technology, Niramai Health Analytix developed AI-based systems for early-stage breast cancer detection.

In agriculture, companies such as AgroStar used AI-driven platforms to provide farmers with real-time information on weather patterns and crop health.

The huge burst of AI innovation until 2017 resulted in AI entering the hype cycle. Thousands of chatbot companies were created riding on this wave. Soon, users and investors would grow disillusioned by the poor output and drop the category lock, stock, and barrel. AI wasn’t ready for mainstream.

By 2018, the global landscape for AI was quietly beginning to build the foundations to explode.

Ecosystem Evolution

By 2019, transformative innovations, pun intended, began to pick up.

It would not be Google that adopted the transformer model, but OpenAI. OpenAI's GPT-2 and GPT-3 revolutionised natural language processing (NLP) and showcased the potential of AI to perform complex tasks with human-like proficiency.

OpenAI first announced GPT-2 in February 2019, and it was released in stages due to concerns about its potential misuse, particularly in generating misleading or harmful content. With 1.5 billion parameters, the model demonstrated remarkable capabilities in generating coherent and contextually relevant text based on given prompts. This was a significant leap from its predecessor, GPT, released as a research paper in June 2018.

The subsequent release of GPT-3 on June 11, 2020, marked a new era in AI-driven text generation. With an astounding 175 billion parameters, GPT-3 became the most potent language model. Its ability to generate human-like text opened doors for various applications across industries, from content creation to customer service automation.

India did not have any LLMs. What it did have was a flourishing IT services and data analytics ecosystem. As the world hunkered down, it would become the foundation for an AI services ecosystem.

Recognizing AI's potential to transform the economy and society, the Indian government took proactive steps to nurture this ecosystem. One landmark initiative was the launch of the National AI Portal (INDIAai) on May 30, 2020. This portal was a comprehensive platform for all things related to AI in India, providing resources such as articles, case studies, reports, and news updates.

The portal garnered significant attention, with over 4.5 lakh users visiting it within its first two years.

Moreover, programs aimed at enhancing skills in emerging technologies have been initiated, ensuring the workforce is equipped with the necessary tools to thrive in an increasingly automated world. The New Education Policy (NEP) introduced in 2020 emphasises integrating AI into educational curricula, thus preparing future generations for careers in this transformative field.

India's AI ecosystem began to follow in this context of global advancement. By 2021, India would still need to catch up in the innovation ecosystem for AI, as most of the research happened abroad. The big irony was that some of the seminal research, like the Transformer Model, in AI was driven by Indians in the US.

By 2022, the country saw a proliferation of over 300 AI startups, reflecting a growing recognition of AI's importance in driving economic growth and improving operational efficiencies across various sectors.

In November 2022, OpenAI was working on AI with little attention. It would quietly launch a chatbot called ChatGPT.

The impact of its launch would be seismic, single-handedly creating a market as it would reach 1 million users in 5 days. AI was ready for its newest hype cycle.

Battling Goliaths

By 2023, the AI market reached a value exceeding $500 billion, driven by advancements across sectors.

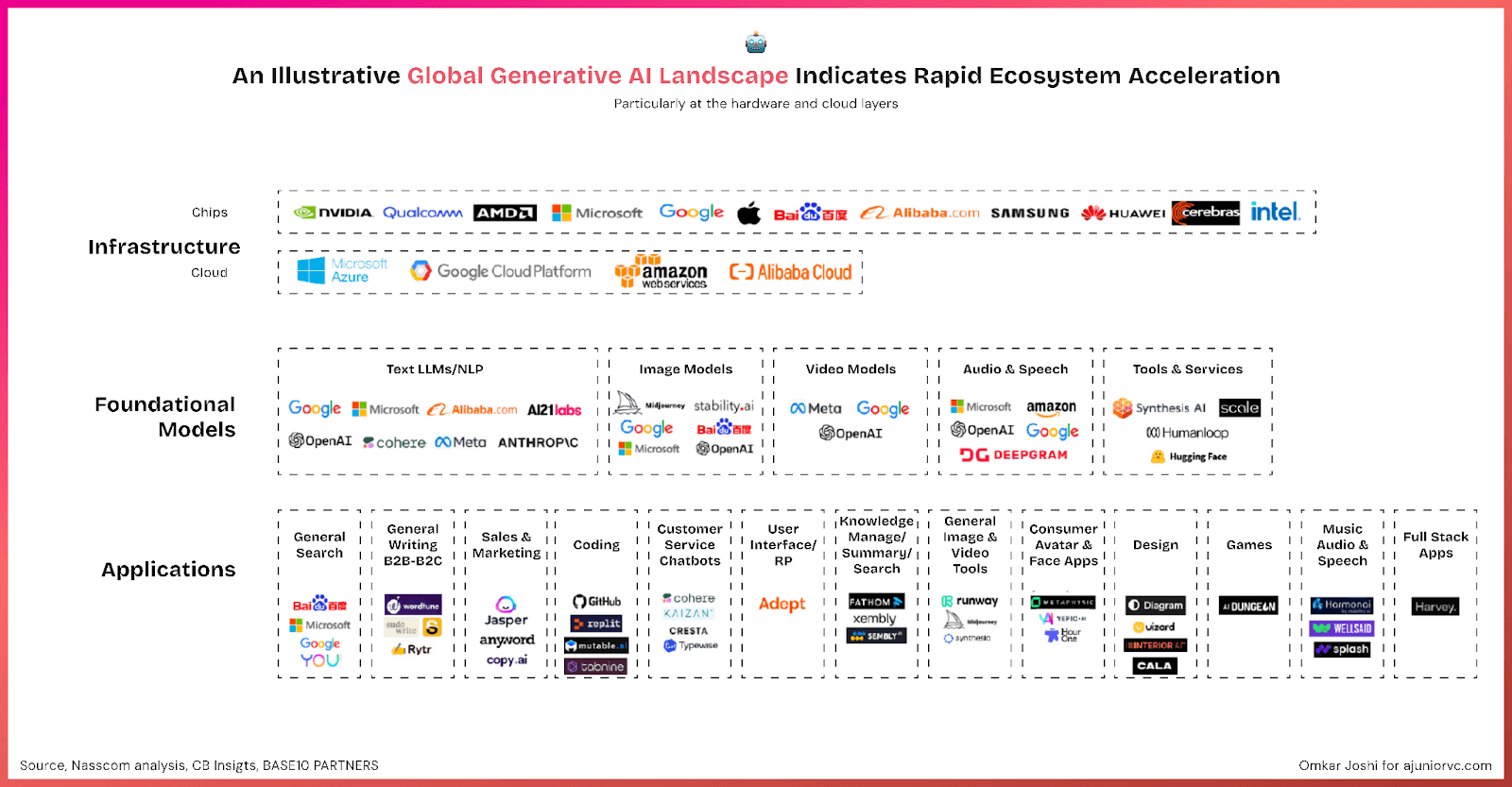

Indian AI was rapidly catching up, not by replicating the LLM race, but by focusing on specific, high-impact use cases tailored to its economic landscape.

Indian AI was on track to potentially contribute $1 Trillion to the country’s expanding economy by 2035. This demand trajectory was anticipated to stem mainly from the financial and telecom sectors, with established incumbents at the forefront of development.

India was also quickly rising in its contribution to AI research, climbing to the 5th spot in research papers filed.

The global race to win AI was heating up

China had intensified its AI development, investing heavily in proprietary models and applications to achieve technological self-sufficiency, contributing nearly 50% of all research papers in the field.

With government support and private investment, China’s tech giants built foundational models tailored for finance, healthcare, and smart cities.

US Tech giants were pouring billions of dollars into maintaining their dominance. Microsoft-backed OpenAI was leading AI innovation, with GPT-4 breaking all benchmarks. Google’s Gemini was powering multimodal capabilities. Amazon-backed Anthropic was trying to build “public good” AI, while Bezos-backed Google killer Perplexity was slowly gaining a foothold.

Though fighting goliaths, India was mounting a robust three-pronged effort—powered by government initiatives, major corporations, and an energetic startup ecosystem.

The Indian government recognised AI's threat and opportunity across the healthcare, agriculture, and education sectors by establishing AI labs in colleges nationwide and launching initiatives such as the National Program on AI. The government aimed to foster collaboration between academia, startups, and established industries.

By 2024, Indian startups had raised $7.7bn in funding, equivalent to just one company's single round, OpenAI. Indian startups were tackling local problems overlooked by giants, from building LLMs in regional languages to agricultural automation.

Startups like Sarvam AI and Krutrim created language models for Indian dialects, opening digital doors to millions who have long been on the fringes of tech. The impact was going beyond languages. In healthcare, Jivi AI has started working to make diagnostics accessible in rural areas, addressing the vast healthcare gaps that global AI giants might miss.

Similarly, KissanAI equipped farmers with real-time data on crop health and yield, directly contributing to higher agricultural productivity and helping a traditionally underserved segment thrive

These use-case-driven innovations demonstrated India’s approach to building AI solutions that respond to specific, on-ground needs rather than focusing solely on large-scale language models.

India’s major corporations were also jumping on board, pushing AI boundaries in their

industries. Reliance, for instance, launched “Jio Brain,” a powerful AI platform that aims to transform telecom, retail, and digital services.

The IT sector was strengthening its capabilities to position India as a generative AI outsourcing powerhouse.

TCS integrated AI to streamline operations and customer service, showcasing the potential of homegrown solutions. Similarly, Infosys focused on enhancing client services through advanced AI-driven tools, while Wipro’s “HOLMES” platform leveraged automation to optimise productivity across industries.

India was positioning itself to make a testing impact on the AI world.

As India developed its own AI landscape, the global conversation shifted towards ethical development, concerns over AGI, and the challenges of energy constraints.

LLMs are Unnecesary

AI is front and centre globally, with nations and companies racing to stake their claim.

Nations view it as key to future growth. AI isn’t optional for startups—it’s essential for investor interest.

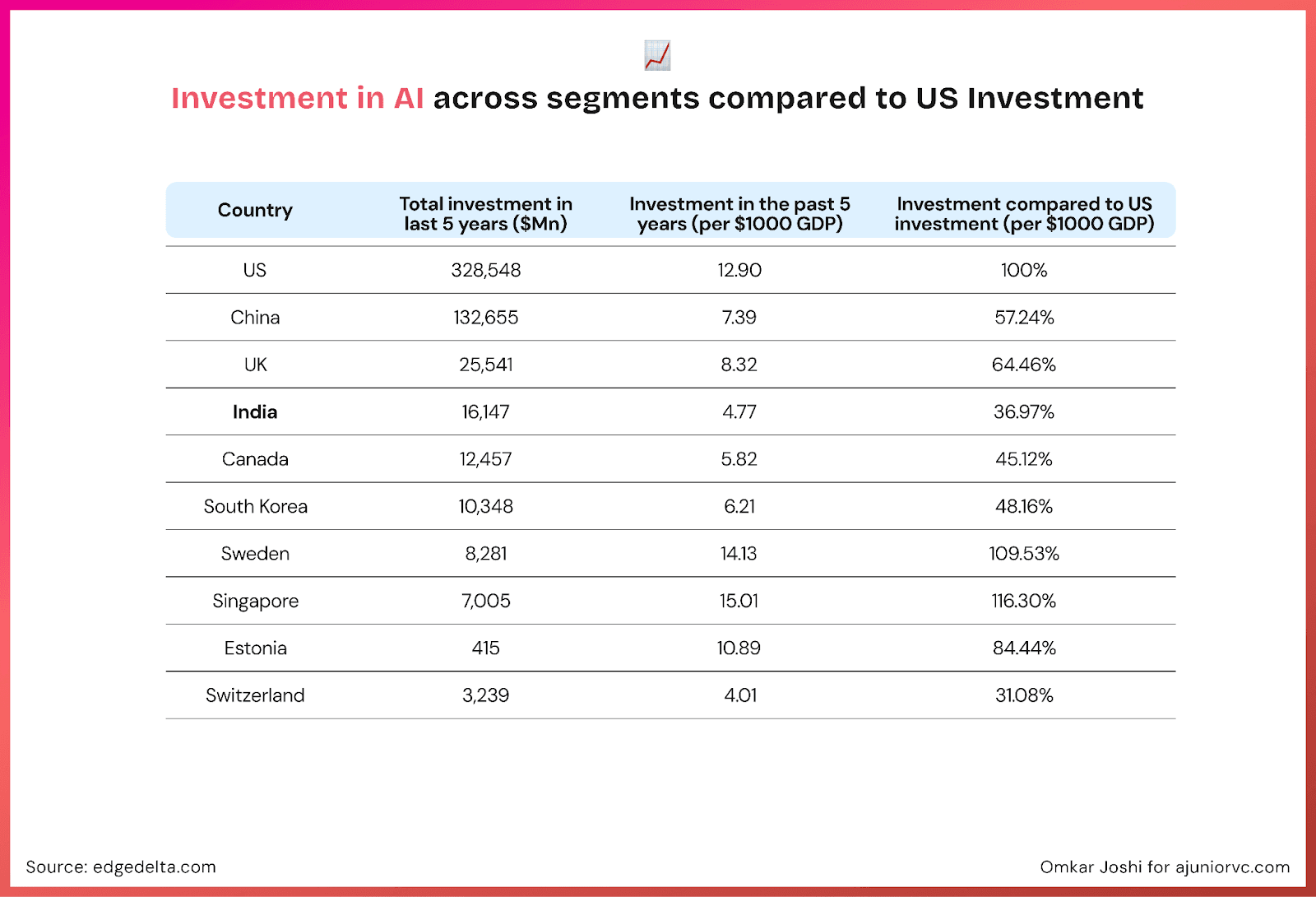

The Indian government has recognised this, launching the India AI Mission with INR 10,371 crore over five years, including INR 4,500 crore for AI infrastructure with 10,000 GPUs. But training models like GPT-4 required 25,000 GPUs to run for months. Competing at that level isn’t practical for India.

The smarter move for India is to leverage existing large models and build on top of them. Remember, India didn’t build the payment infrastructure that Visa / Mastercard did. But when the time arrived, and the need was apparent, India built UPI. Our country's lifecycle needs demand what we should build, rather than idolatry.

India’s stage as a country does not require the building of LLMs

Training LLMs are costly and resource-heavy, demanding top talent and substantial energy. Instead, focusing on application-driven innovation allows Indian companies to direct resources into fine-tuning pre-trained models, creating targeted solutions, and upskilling their workforce.

Solutioning and building applications using technology is in India’s DNA, as close to 30 years of the IT and data industry has shown.

The payoff? More impactful results, faster. India’s startup ecosystem shows this works. A report revealed 77% of startups invest in tech like AI, and it’s paying off.

Fintech player ZestMoney uses AI for better credit scoring; edtech platform Embibe personalises learning, and Wysa’s chatbot offers mental health support. Even major players like Flipkart, with its AI assistant Flippi, show how applied AI enhances user experience by understanding nuanced requests like, “I need a phone for my grandparents.” Razorpay uses AI for real-time payment fraud detection, boosting trust and security for digital transactions.

In agritech, CropIn leverages AI for predictive analytics, helping farmers optimise yields and reduce risks.

Building on existing models makes AI development more accessible, empowering smaller firms to innovate without the high costs. Companies like Haptik and Yellow.ai started simple but evolved into sophisticated platforms. Logistics company Delhivery uses AI for efficient route planning and supply chain optimisation, while health startup Niramai applies AI in breast cancer screening using non-invasive methods.

This approach also adapts AI to local needs, enhancing impact through language, cultural nuances, and behaviour insights. Collaborative ecosystems involving the government, academia, and industry, combined with a focus on quality data infrastructure, will set India apart.

India’s future in AI isn’t about building the biggest model but making the most meaningful applications that serve its unique needs and people.

AI = IT 3.0

Applications for many use cases will create the future for India’s ecosystem.

We have the horsepower and talent to imagine, build and create technology solutions. As Jensen Huang rightly quipped, India should focus on manufacturing intelligence and exporting AI solutions. India has all the ingredients for this path.

Creating multi-step reasoning and agentic applications has opened up an entirely new ecosystem for India. The use cases could be myriad. Anything that involves white-collar professionals is fair game. This could mean legal, compliance, financial services, investing, or coding.

Collaboration and strategic policy are crucial for nurturing the next wave of AI startups in India.

The government’s IndiaAI Mission is a testament to this commitment, with initiatives to tackle significant challenges for emerging AI enterprises. By streamlining access to high-quality datasets, developing Indigenous LLMs and domain-specific models, expanding AI education, and supporting deep tech funding, the government aims to foster an AI ecosystem that thrives on innovation and responsibility.

However, the reality for Indian AI startups isn’t without hurdles. Funding dropped nearly 80% in 2023, down to $113 million compared to $554 million in 2022. This starkly contrasts with the U.S., where AI funding surged 211% to $16.2 billion. Despite the funding gap, this challenge can drive frugal innovation, an area where India excels, as evidenced by cost-effective successes like ISRO’s Chandrayaan-3 mission.

India’s deep expertise in IT services, data science, and analytics uniquely positions it to lead the development of impactful AI use cases.

Unlike the pursuit of developing global LLM leaders, India’s strength lies in harnessing AI to solve practical, real-world challenges across sectors. Emerging technologies like machine learning-driven healthcare, predictive analytics, and AI-powered language processing are already in play, showcasing the potential to scale impactful solutions.

For example, NIRMAI’s AI for early breast cancer detection highlights AI’s potential in healthcare, while Upliance AI automates domestic tasks, easing daily life for millions. Companies such as AI4Bharat and Krutium are pushing the boundaries in language AI, ensuring non-English-speaking populations benefit from technological advancements. Karya AI stands out for leveraging technology to create opportunities for disadvantaged communities, showcasing AI’s potential for social impact.

Startups are addressing supply chain and infrastructure challenges, fostering a cycle of innovation. Companies like upGrad are boosting AI skillsets, while Fractal and Mu Sigma contribute globally to AI talent. RagaAI’s work on LLM safety underscores the focus on responsible AI.

India’s history with analytics, IT services, and data science lays the foundation for robust AI applications that span industries—from finance and healthcare to education and logistics.

With a supportive government policy push and a unique talent pool, India is well-positioned to build globally significant AI use cases. This trajectory ensures that AI innovation is not just about leading in technology but leveraging it to empower communities, bridge accessibility gaps, and strengthen India’s position in the global tech ecosystem.

India’s 30-year IT explosion has positioned it well for the next global decade-long AI renaissance.

Writing: Parth, Chandra, Raghav, Varun, Tanish and Aviral Design: Omkar and MJ