Jun 13, 2021

Can India Consume D2C Brands?

Beauty

Babycare

Retail

Brand

B2C

Fashion

Last fortnight, D2C brand acquirer Mensa raised $50M, hot on the heels of beauty brand SUGAR’s $21M fundraise.

It Starts with One Flip

It was January 2007, as Binny Bansal was fiddling on his desktop.

Binny had just joined Amazon through a referral from Sachin Bansal, who had been working at Amazon since 2006. Binny and Sachin were acquaintances from their time at IIT Delhi.

Eight months in and Binny realised that working for Amazon did not satisfy his itch to do impactful work. Amazon had yet to start its e-commerce business in India, and he felt like his job just wasn’t fulfilling enough.

Binny had become good friends with Sachin by then, and they both decided to resign and start a business of their own. One would think that Flipkart was the first e-commerce website to launch in India, but that was not the case.

Although only 4% of Indians used the internet in 2007, many e-commerce websites served Indian users. Sachin and Binny made a website that helped users compare the prices of different products across different websites.

Soon they realised that the e-commerce websites in India needed vast amounts of improvement. The user experience was terrible, customer support was non-existent, and most of them had horrible interfaces.

The Bansal’s knew that they could do better, so they launched their online bookstore and called it Flipkart.

The story of how they got their first customer is fascinating, and by 2009, Flipkart was ready to raise their first-ever round of funding for $1 Million from Accel.

Flipkart soon pivoted to an e-commerce website that sold all kinds of products. Its pivot would turn out to be the trailblazer for an entirely new way of doing business.

Selling “direct to consumer”, or D2C.

Arriving Somewhere, But Not Today

As Flipkart scaled and showed the way, many oceans away, a US startup would also lead the way.

Started purely online in 2007, Bonobos would start slowly in its first few years. But by 2011, Bonobos had scaled so much that traffic crashed its website on Cyber Monday.

Bonobos’ runaway success inspired a stampede of US brands. Indian founders were not far behind.

All this was not steeped in herd mentality but hard business logic.

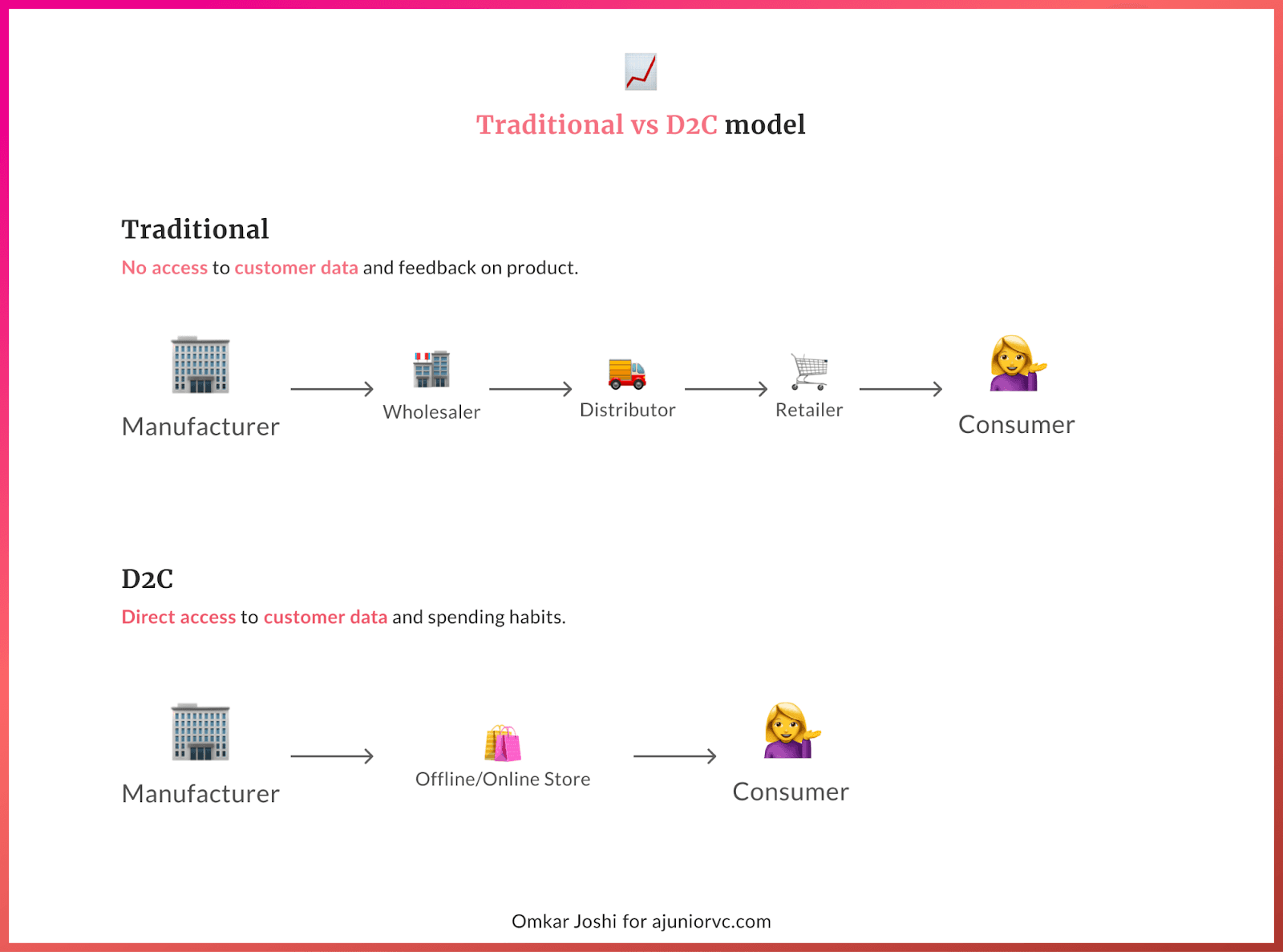

In D2C, companies had complete control over the distribution channel. The companies no longer had to depend on wholesalers, retailers and other intermediaries. Brands had to distribute the product to the customers, but they could decide how they wanted it.

The control of the supply chain would bring in a significant impact on profitability.

Since the company no longer has to pay the intermediaries, they can keep a more significant profit share. Products could also be priced lower. It worked in favour of the consumers because now the company can sell the products at a lower price.

Working in favour of the customer brought these brands powerfully close to the customers.

Due to their proximity, they could see the customer's whole journey. This led to deeper insights into consumer behaviour and helped the company ideate and iterate faster. Direct access to consumers also meant more opportunities for upselling and cross-selling across multiple product lines.

Getting deeper customer insights was perhaps the most compelling reason for brands wanting to go D2C.

But in India, startups needed to solve a different problem before that.

Lack of trust was the biggest hurdle in the adoption of D2C. Internet penetration was still at its nascent stages. Smartphones were still a luxury that a select few could enjoy. Logistics costs were through the roof, something that low volume upstarts couldn’t afford.

SUGAR started as FabBag in 2012, on the promise of D2C seen in the US. It brutally faced the headwinds that existed at the time.

For D2C to work, a lot of factors were yet to come into play.

Get in Closer, We’re going Direct to Customer

By 2013, there were ~100M internet users in India.

Various surveys said that social media reached 60% of the online population. Facebook had the highest reach among all platforms.

Like Nike, Adidas, Pepsi, and Canon, big brands were already using social media platforms to run brand campaigns. However, traditional advertising channels were still dominant in getting the consumer’s attention, and brands continued relying on retailers to reach the consumers.

This is what was called the Indirect Brand Economy, where a product exchanged hands multiple times before finally reaching the customer. The lack of direct access to consumers also meant that brands had a tough time getting feedback for the products they sold.

If a customer did not like the product, they would either return it to the retailer or stop purchasing it altogether. Back then, one couldn’t go on Twitter to write a post tagging the company’s handle and the CEO to voice their dissatisfaction. Brands had to rely on surveys and feedback from retailers about their products.

Fuelled by the explosion of the internet, the Direct Brand Economy started to finally gain traction.

Companies like glasses manufacturer Lenskart, lingerie retailer Zivame, online jewellery store Bluestone and many others were starting to pick up steam. Beauty products marketplace Nykaa were just getting started.

These early players capitalized on changing consumer attitudes in India due to rising incomes and exposure to new ideas and technologies. Consumers, especially in the urban areas, evolved and expected a seamless shopping experience across every channel.

This could be in a brick-and-mortar store, an e-commerce website, a mobile app or a customer-service phone call.

The Indian direct to consumer establishment was still in its nascency and was growing quickly.

The US, though, was entering the second wave of its D2C revolution. Stories like the D2C poster boy “The Dollar Shave Club” were going viral with their commercials.

Building a store and reaching customers online was easier than ever before in the US. Enablers of their success, Shopify and Amazon launched in India in 2013.

The time had come.

I am the one Who Knocks

Indian D2C was finally beginning to take off.

Early success stories along with US infrastructure and distribution channels resulted in an exponential growth in Indian brands.

At a minimal cost, businesses could build their own online stores in-house in a matter of hours. This would save the cost of hiring a team and months of effort to build the infrastructure to serve customers.

Not only was it now cheaper to start an online store but Shopify also allowed individual store owners to use sophisticated analytical tools. Individual retailers could understand revenue by traffic streams, see which products aren’t selling, and make data-driven decisions accordingly.

Companies could now build much faster and reach niche consumers on the internet at the right moment.

Come 2014, it was still a challenge to ship economically across India. Companies like Delhivery, Bluedart, DHL, and Ecom Express were starting to emerge. Local infrastructure was making it possible for brands to fulfil orders at scale.

Access to cheaper scalable infrastructure lowered the entry barrier for new players. A flurry of Indian brands emerged in lifestyle categories like apparel, beauty and home furnishings and CPG categories like food and beverage and personal care.

Their unique business models allowed them to talk directly to consumers and tell them their story. Brands could cater to the needs of millennials and give consumers the convenience they demanded.

The direct to consumer landscape was maturing rapidly. With more tech-savvy brands armed with data, it was easy to get started.

But it was now much harder to scale.

As more brands competed over the same groups of customers, acquisition costs started to rise. At the same time, consumers had more options and it was harder for brands to retain them.

By 2015, strategies that worked for the incumbents no longer worked for new entrants. Changing the equation for direct to consumer startups.

Innovation was the need of the hour

You Can have your Cake and Eat It

Reaching customers on social media was revolutionary in 2012, but mere table stakes in 2016.

Intense competition against data-rich brands over the same eyeballs meant that each newcomer had to reach customers on multiple channels.

Looking for the edge, a new digital distribution strategy started to emerge - omnichannel marketing.

The idea was to use all of one’s channels to create a single unified experience for one’s customers. This included both traditional and digital channels, point-of-sale, in-store, and online experiences.

Brands like Lenskart and Nykaa that started as “disruptors' of the old retail way, now were expanding into physical stores.

The rationale lay in, you guessed it, going omnichannel.

Customers had to build up trust with an e-commerce brand before they felt comfortable enough to purchase from them. For brands, getting potential customers to visit their website was not enough.

They had to maintain end-to-end communication with customers till the purchase was made.

An example of this strategy would be re-targeting customers that had abandoned a product midway through the purchase process. Adding relevance and nuance to advertising was a competitive advantage.

Putting customers at the centre of communication rather than blindly pushing their array of products allowed brands to forge a much deeper connection.

Omnichannel marketing was built such that it put the customer at the centre of the strategy. The marketing strategy and the message would adapt to how the customer had previously interacted with other channels.

By 2017, companies like Nykaa and Lenskart were successfully leveraging this strategy. Being direct to consumer allowed them to be “omnichannel”, unlike their older counterparts who relied on multiple forms of middlemen

Innovations in marketing gave brands a plethora of ways to acquire customers, but the customer was now spoilt for choice. Retaining customers was the only sure shot way for these brands to stay afloat.

Community building would be the answer.

Come for Product, Stay for Community

The customer in D2C was core, and innovations on keeping the customer hooked continued.

What started with purely social media, evolved into omnichannel, and was now turning into community building. Along the way, storefront and logistic enablers gave the shovels in the D2C gold rush.

As costs of acquiring customers shot up, building these communities became crucial for a profitable D2C brand. For many founders acquiring customers without spending money on ads became a badge of honor.

Platforms like YouTube, Instagram and Facebook allowed brands to reach and connect with millions of uses for free.

Inspired by dollar shave club’s legendary homemade YouTube video which propelled the brand to a billion dollar exit, Indian brands also started to get creative.

As the brands entered 2018 trying to build these communities, another group of individuals started to benefit.

The Indian “influencer” was born.

As influencers helped improve the “personal touch” with customers, companies began allowing them to access specific content or discounts on a regular basis and charged them a few dollars in exchange.

Subscriptions finally entered India, and along with it was born the next wave of growth.

This idea transformed the entire D2C industry as it gave them a route to be lean and be profitable. It was now time for D2C companies to increase the pool of users so that a certain percentage would pay for premium content/discounts and would lead to a path of consistent cash flow generation.

By now, companies had a sense that there was a real opportunity in the market if they managed to scale. Some companies did scale, but for them sustainability was the key.

This provided much needed impetus to India’s D2C wave.

With the help of technology and social media, brands could deliver fashion to their customers’ doorsteps (Nykaa), could venture into unconventional businesses (Licious) and could challenge the status quo with community-driven moats (boAt).

Solid business models, validated by customer feedback would inevitably pique the inventor's interest.

Fashionably late to the party, India’s D2C moment was here.

You’re Gonna need a Better Moat

As the D2C playbook evolved, so did the kinds of companies going D2C.

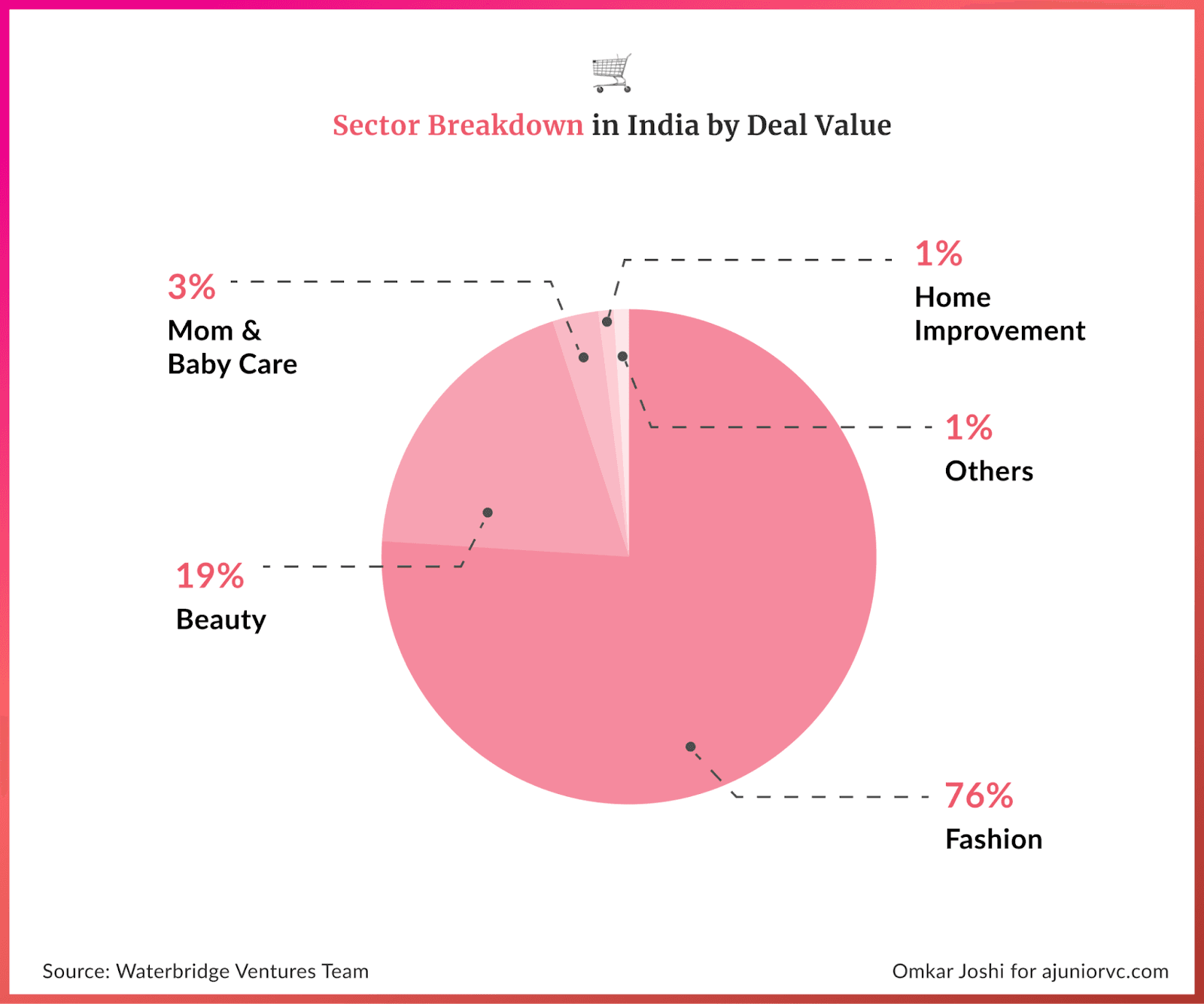

Fashion and beauty turned out as the largest segment in the market, both in India and globally, and drove maximum interest, thanks to social media and the rise of micro influencers.

There were also companies that wanted to scale niche segments, such as healthy food, ayurvedic wellness and yoga products.

With more than 600 brands across the sectors D2C became one of the largest, and fragmented spaces. This phenomenon was bound to unfold given the sharp online growth indicators in the Indian economy.

The last couple of years witnessed a tremendous rise in the number of shoppers in India, going from 50M to a staggering 130 Mn.

The rise in the number of online shoppers also shaped the consumer evolution.

With a mix of aspirational, gender-diversified, millennial and content driven consumer base, the supply had to evolve to respond to changing needs and establish a faster and close-to-consumer feedback and value chain.

The roots of this phenomenon could also be observed with the early 2020 trends of consumers wanting to shift from the e-commerce marketplaces to direct brand websites. There was a 65% increase in brands developing their own website in India, which led to subsequent increase in self-shipped orders in 2020.

Among the multiple global trends that have colored the Indian economy, market thesis and sentiments, this one qualified as one on the top.

The customers increasingly wanted to have a deeper look at what they are buying and take an educated call by listening directly to what brands had to say.

Another key fact to be brought to light is that India, as a retail market, was largely unorganized.

With the retail economy being close to a $1 Trillion, India’s organized retail penetration stood around just 17% in 2020, projected to reach a target of 30% by 2025, but this number is still lesser than that of example economies like US and China, with ratios of 85% and 55% respectively.

The fragmentation of D2C was part of the creative destruction underway, fuelled by investors.

Look How far We’ve Come

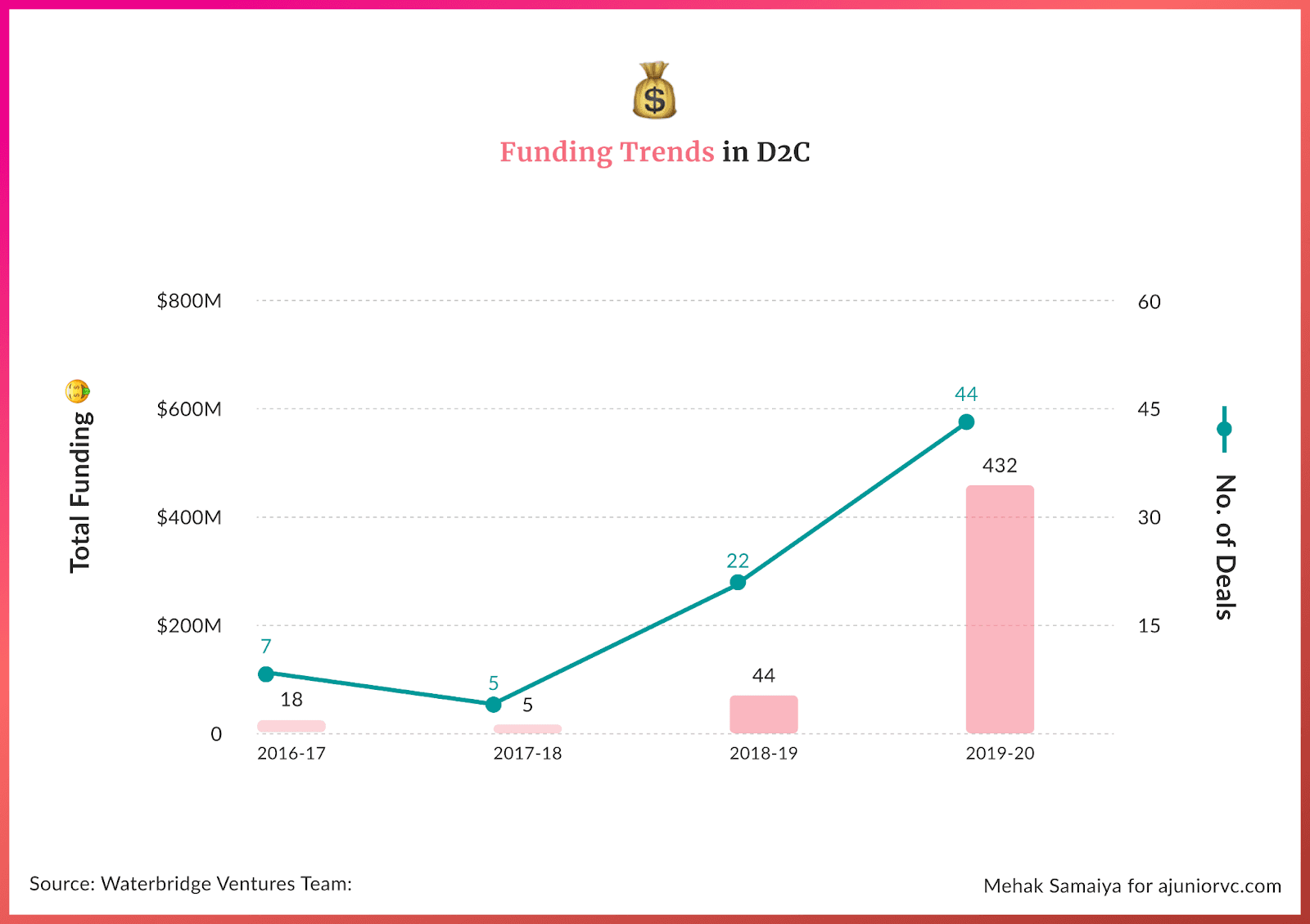

The growth in D2C space was underwritten by multiple investors.

This was seen in the amount of funding that has flowed into the space. Half a billion dollars in the last four quarters, showed the hockey stick in funding.

By 2020, the space has seen $1.6B of funding across 100+brands.

Innovations continued in every way, including the product, the model and the distribution channel. D2C brands rode on business models different from the traditional ones.

With the power to control manufacturing, supply chains, distribution channels, ability to have visibility to customer data, feedback and insights have enabled the business to structure the PnL differently.

As we saw due to D2C’s vertical integration, they observed higher gross margins, which left money on the table to experiment with innovative marketing channels.

Eventually, D2C brands would end up on a similar operating margin structure. They would rather not spend too much on traditional distribution, but leverage the tech platform play for distribution – and that’s where their consumer is.

This model of high gross margins, high economies of scale has proven to be practical and explosive.

D2C brands have taken less than 30% of the time to reach a scale of INR 100 Crores in revenues when compared to traditional counterparts.

Case in point, Mamaearth was competing against giants like HUL and P&G but the D2C route allowed them to scale quickly, and how. Reaching a INR 500 Cr revenue run rate in less than four years was a rare feat; one that was made possible by the power of D2C.

It was clear that this route was powerful, profitable and scalable. As Mamaearth set the trend, multiple other brands followed suit in the wave.

But before there was a massive roadblock incoming.

May the Force Be with You

Even though D2C brands were online, they sold fundamentally physical products.

As the pandemic struck in 2020, brands like MamaEarth, SUGAR and others were hamstrung. With physical lockdowns in force, most went to zero.

But what seemed like a death knell, would only turn out to be a blip in an already aggressive growth story. As the nation unlocked but people stopped setting foot outside, delivering to customers at their doorstep became the only option.

Direct to consumer was not a way, it became the only way. The entire infrastructure that these “little” brands had setup now became leading lights for large conglomerates scrambling to reach the customer directly.

This customer was only becoming more perceptive, higher income and shopping online.

Driven by a growing economy, India’s ecommerce is expected to reach a giant pool of $200bn by 2025.

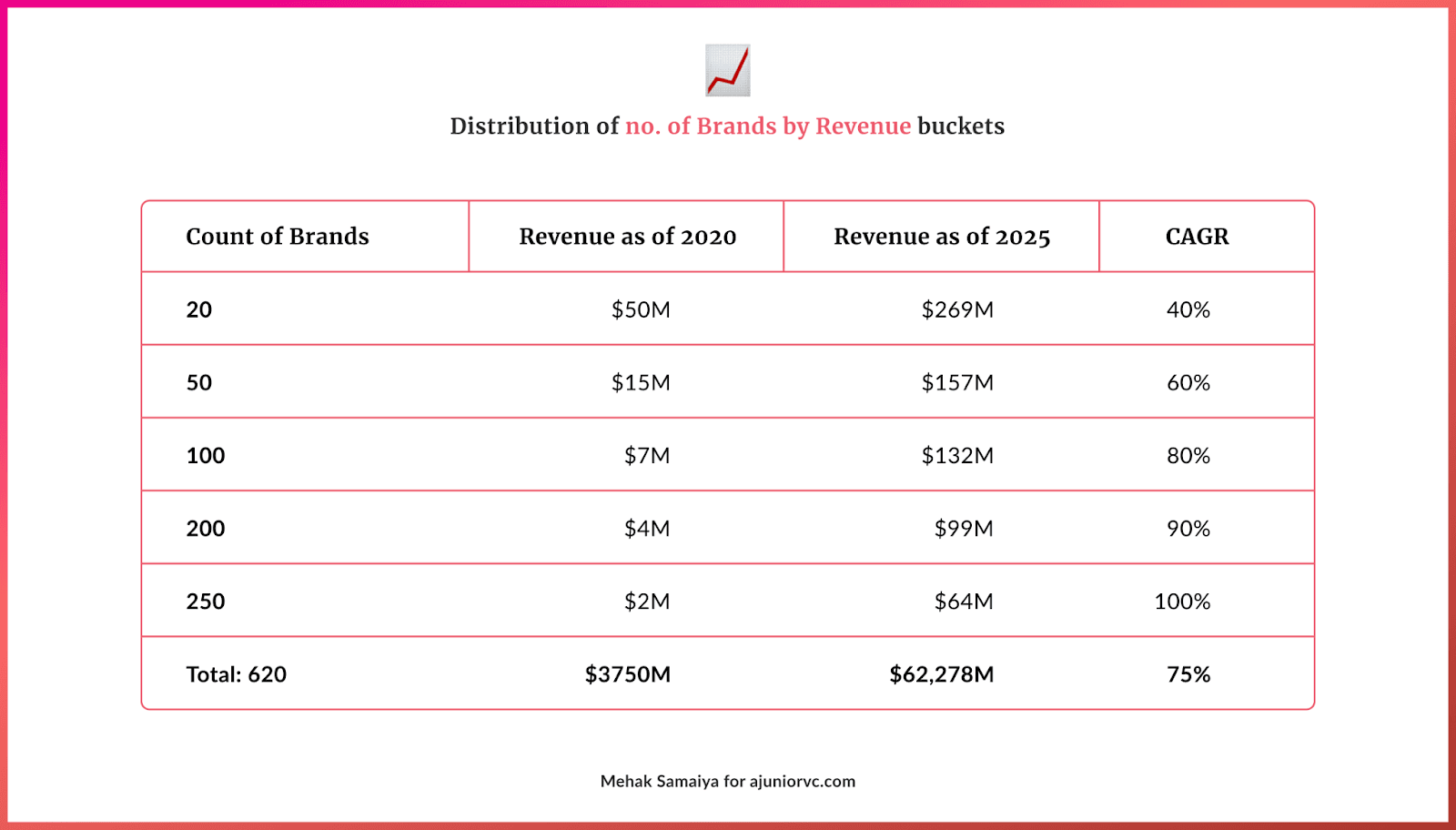

It is clear one of the strongest drivers would definitely be D2C. Our analysis of the future potential of this market puts the revenue potential at $62Bn.

This would also say the CAGR for D2C is ~75% for the coming years, which is almost double than that of etail at 40%.

Accelerated by the pandemic, the rapid growth in tech startups hasn’t gone unnoticed with incumbents. The new-age digital and tech plays have attracted the traditional setups across industries including heavily regulated financial services and healthcare markets.

A similar trend is shaping up stronger than ever in the D2C.

Large incumbents who realize the power of leveraged distribution and high economies of scale on the back of tech, are acting early through strategic acquisitions.

There are clear winds of consolidation in this highly fragmented market.

There have been numerous examples like Beardo’s acquisition by Marico, PipaBella’s acquisition by Nykaa (A bigger D2C acquiring a smaller D2C brand) and even bigger global sales like that of Drunk Elephant and Have & Be close to $1Bn each.

The incumbents would use these agile brands in their portfolio to fill the missing pieces in their strategy for tailoring the products to exactly what consumers want.

As Flipkart enabled the new business model of D2C brands, the explosion of D2C brands is now further enabling newer business models.

Given this growth, a class of investors is looking at this space not only as an avenue of potential equity investment but also for Revenue based Financing.

A type of financing where the investors just underwrite a conservative revenue growth and expects a 10-15% interest on their capital in the form of ongoing revenue share.

These are not just the only ways for growth or exits for the D2C brands. India is also in a race to build a “mega-acquirer” for D2C brands.

Thrasio, which is the world’s largest acquirer of third-party private label businesses on Amazon. Thrasio acquires, consolidates and scales the brands under its own portfolio of house of brands.

This trend has been fast gaining traction in India with numerous examples. Firstcry is launching a $75M investment vehicle to replicate a Thrasio style model in India. Similarly Mensa Brands launched with a monster $50M series A.

After hiccups and roadblocks at the start of the decade, D2C brands have now completed the full circle in becoming a platform for other businesses. As we enter this new decade, D2C brands are only getting bigger, faster and sexier.

India is ready to consume D2C, with a voracious appetite.

Story by Bhoomika, Mazin, Saniya, Omkar and Aviral | Visuals by Omkar, Mehak and Saumya