Apr 14, 2024

Is Cafe Coffee Day's Rollercoaster on a 5,000 Cr Turnaround?

Profile

Food

Brand

IPO

B2C

Retail

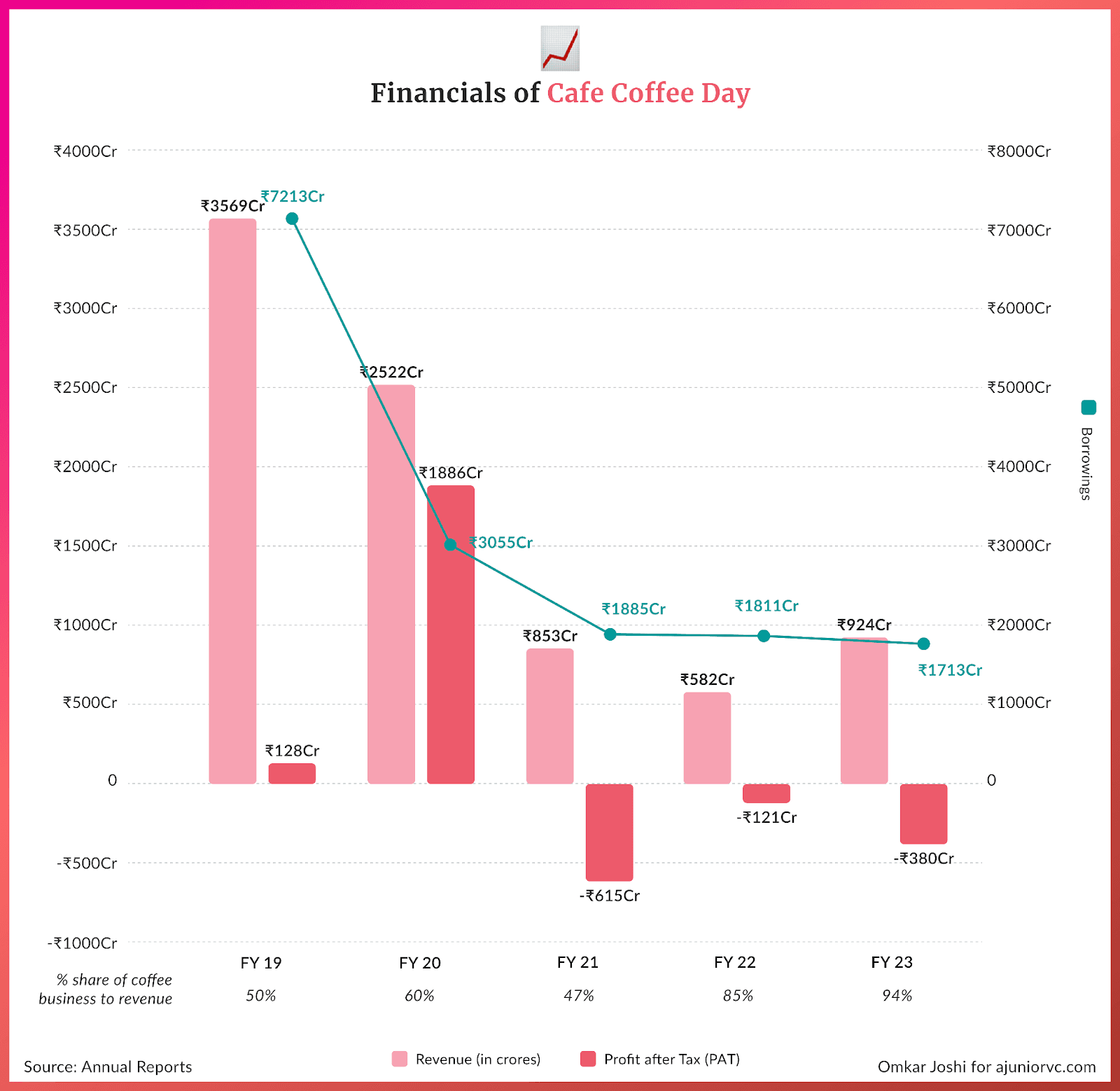

From INR 7K Cr debt in 2019 to closing FY23 with just INR 1.5K Cr in debt, CCD started last fortnight and FY24 with a 15% stock market bump

Rise And Grind

Veerappa Gangaiah Siddhartha Hegde was born in a family with a 140-year coffee-growing history in Chikkamagaluru, Karnataka.

Initially, he was keen on joining the Indian Army. Over time, he developed an interest in finance and aspired to become an investment banker.

He earned his master's degree in economics from Mangalore University. At the start of his career, VG Siddhartha invested heavily in the stock market. When he was 24, he was employed by JM Financial and Investment Consultancy in Mumbai.

He worked there as a Management Trainee/Intern in portfolio management and securities trading on the Indian Stock Market.

After spending two years with JM Financial, Siddhartha returned to Bangalore.

In 1984, he launched his investment and venture capital firm, Sivan Securities, in Bangalore. He began investing the profits from his start-up in buying coffee plantations in Karnataka's Chikmagalur district.

By 1985, Siddhartha had started investing full-time in stocks and acquired 10,000 acres of coffee farms.

Around this time, he became interested in his family's coffee business. In 1993, he set up a coffee trading company called Amalgamated Bean Company (ABC) with an annual turnover of over INR 6 Cr, scaling it to INR 2.5K Cr. over the years.

With the aid of ABC, Siddhartha could trade over 20,000 tonnes of coffee from his crops, which were now producing 3,000 tonnes yearly. As a result, the business grew to become the 2nd largest exporter from India in about two years.

Soon, an interaction with the owners of Tchibo, a German coffee chain, helped Siddhartha look for a larger opportunity. He decided to open his cafe chain in a country with no formative cultural grounding in cappuccinos.

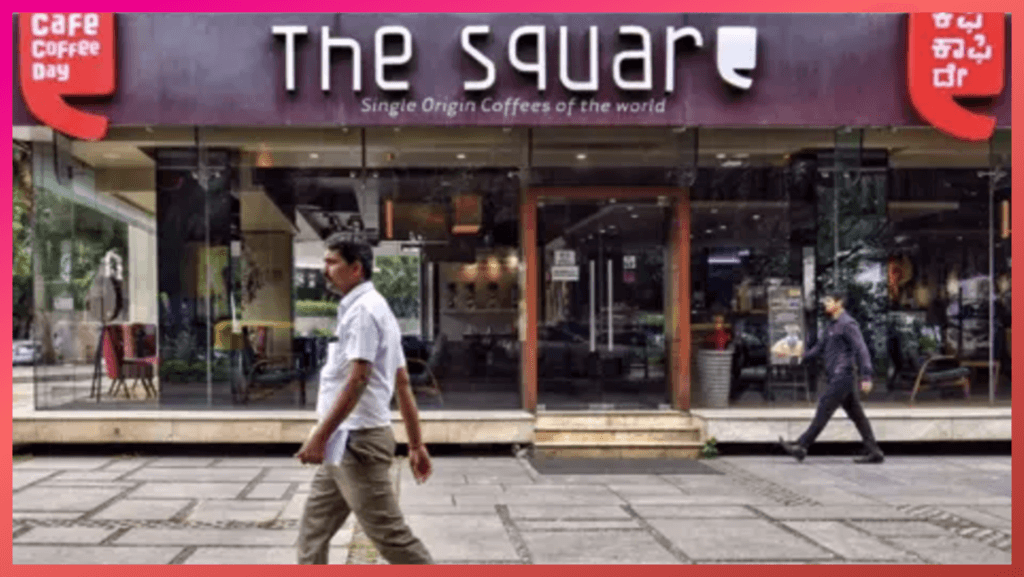

He opened Cafe Coffee Day's first outlet on Bangalore's upscale Brigade Road in 1996 with the tagline 'A lot can happen over a cup of coffee'.

CCD was born.

Brewing a Storm

The business quickly gained significant recognition for its ground-breaking idea, which allowed millennials to converse while enjoying their preferred beverage.

Once the Indian government opened up the economy in the early 1990s, it led to a rapid increase in income for the Indian upper and middle classes.

The IT Industry was growing, and India became the epicentre of this growth. Young Indians started travelling to other countries for business and work. They had disposable income, and their desire to try new things and have conversations over coffee at a cafe grew rapidly.

Siddhartha could see this only growing from here, and the success of Brigade Road Cafe made it clear that India will have hundreds and thousands of such cafes.

CCD did three things to ensure that they stayed ahead of the business.

Knowing the value-conscious Indians, CCD focused on affordability so that everyone, from college students to professionals, could afford a coffee at a CCD.

The chain then focused on accessibility to ensure a cafe in almost every other neighbourhood. Finally, the focus involved building product acceptability by considering the tastes and preferences of Indian consumers.

Word of mouth did the rest, and people flocked to CCDs. Siddhartha took his time to understand and build this playbook.

From 1996, it grew to only 18 outlets until 2001, as he wanted to ensure they had a solid base before they pressed the accelerator.

The consistency across all cafes, the brand and the top-of-mind awareness ensured that CCD tables were well occupied.

It was time for them to push the paddle.

A Perfect Blend

By 2004, CCD had opened its 150th cafe, including ten book-and-coffee outlets.

They had cracked the secret recipe for growth and were onto something extraordinary. To fuel this remarkable growth of retail outlets, Siddhartha needed money.

That’s when he turned to leverage his existing network of friends and family, who were happy to help him take their 140-year-old coffee business to a new height.

By 2006, CCD was expanding and growing in India and abroad. They needed a strong financial backer with an understanding of international markets to fuel this growth. Siddhartha raised $20 million from the India arm of a leading American VC firm.

The aspiration of becoming a Global brand took CCD from India to Vienna, the world's coffee capital. By 2008, CCD opened a cafe in Vienna, and now the world was having conversations at a CCD.

CCD was now available in 102 cities with over 620 outlets. It was way ahead of its competitors like Barista regarding network and growth. By the end of the year, CCD planned to cross 900 outlets and clock a revenue of more than INR 700 Cr.

Investors loved the growth story, and by 2010, KKR, and other leading investors, had pumped $210 million into CDR (Coffee Day Resorts). This relationship was a huge positive, but time would tell how it would eventually play out.

CCD touched an approximate revenue of $45M in 2010 and generated employment for 5000 employees. It owned 1K+ cafes in 135 cities.

CCD adopted the vertical integration model early on. CCD owns its plantations, produces coffee, prepares espresso machines, and creates furniture for its outlets. This model enabled cost-cutting and quality control at the same time.

The cafe chain delved into a culture where people could now bond professionally and personally over a classic non-alcoholic beverage, delicious food, and craft fully architected seating spaces.

It served cult favourite international drinks like cappuccino, latte, and traditional Indian beverages. It marked a successful attempt at building access to homegrown brand spaces, giving a taste of a similar, if not better, experience than other international food labels prevailing at that time.

CCD had the world for the taking.

Grounds For Celebration

Siddhartha's next goal was to make CCD the world's top 3 retail coffee brands.

Purely on coffee number outlets, he aimed to design 2K stores in India and 200 overseas, mostly in Eastern Europe, to compete with Starbucks, Tim Hortons, and other premium coffee brands globally in the next three years.

The proposition was simple. Step into a CCD outlet for a universal bonding experience over coffee, making work fun and informal. 57% of CCD’s revenue came from the 20-30 age group who preferred the comforts and aesthetics of a cafe to work and socialise.

It became popular for its seasonals and festive food and beverage delicacies. Further, it partnered with complimentary brands like Dunkin Donuts.

It progressed with the international culture of getting coffee on the go and launched CCD Express. The new service offered a range on the go for customers who preferred quick service and premium tastes, and it was available in airports and movie halls.

By 2011, CCD had expanded its network to more than 1000 bistros across India and was growing fast.

After sailing through for more than a decade without any serious competition, CCD started to feel the heat in 2012 with the arrival of international chains in India, including Starbucks and Costa Coffee.

In the face of competition, CCD differentiated itself based on affordable coffee, good ambience, and quality service.

Backward integration meant CCD could beat its competition on price and scale to corners of the country where its competitors could only dream of going, like Leh in Kashmir.

A small cappuccino at a CCD outlet in New Delhi cost INR 79, while a Barista offered the same product for INR 90 and Starbucks for INR 120.

The price was a moat.

While CCD targeted young people who wanted to pay at most $1 to $1.50 for a coffee, it also opened a few lounge-style outlets focused on premium customers, who did not mind spending more money on added services.

The dizzying growth of CCD was unstoppable.

Bean There, Doin’ That

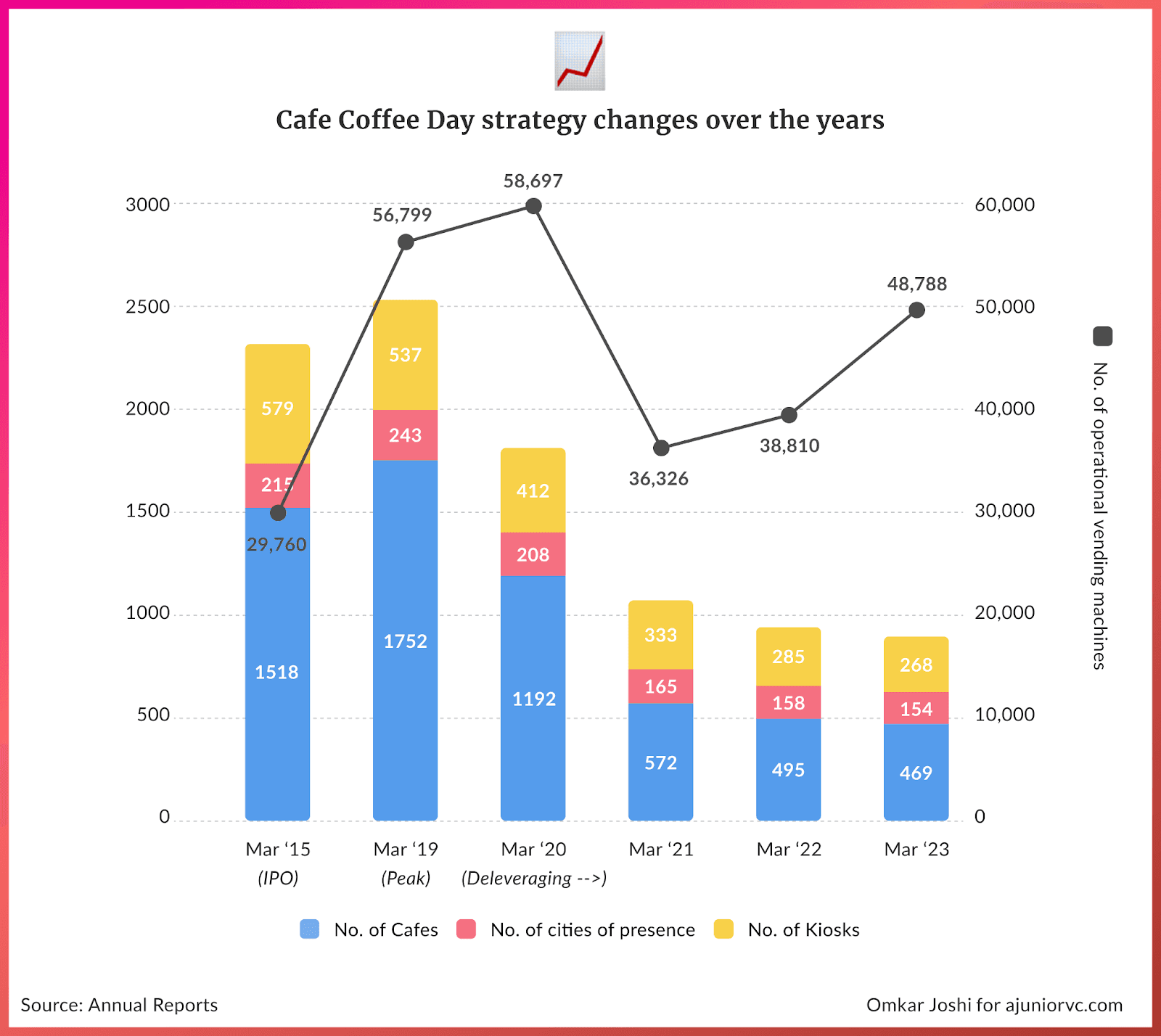

By 2015 CCD had expanded to 1,513 cafes across 219 cities in India.

These were all buzzing. The second largest player by store count was Barista Coffee, which had 165 cafes, while Starbucks operated less than 100 outlets nationwide.

With the expansion plans playing out nicely, Siddhartha decided it was time to access the public markets to raise capital and continue the unfettered growth.

Coffee Day Enterprises Ltd (CDEL), the parent company of the Coffee Day Group, which housed CCD outlets, went public in October 2015.

CCD was the 2nd homegrown food and beverage company to go public, after restaurateur Speciality Restaurants Ltd in May 2012.

The response to the IPO was tepid. The listing saw the company garner a valuation north of $1B, but on November 2, when its shares debuted on BSE, it ended the day at INR 270.15 apiece, down ~18% from its issue price of INR 328.

The disappointing IPO was attributed to CDEL’s varied business interests, while their existing investors considered them ‘balancers’, which would play out in the long run. CDEL had business interests in real estate (technology parks), logistics, financial services, hospitality, and information technology.

As of FY14, CDEL's coffee business—which included CCD, a coffee vending machine business, an export business, and a chain of coffee retail stores, Fresh & Ground—reported INR 1,144 Cr in revenue, accounting for 50% of its total revenue. The group’s logistics business accounted for 36.9% of revenue, followed by financial services (7.53%) and technology parks (3.30%).

The public markets wanted to buy a coffee consumer story. They were interested in something other than logistics, hospitality or financial services. Within a year of CCD’s initial public offering, 2,000 bistros had spread nationwide. CCD also began to take on debt to service all of its expansion.

However, the company had to slow its expansion because of cutthroat competition.

Spilling Beans

The 7,000 Cr explosively growing coffee market kept attracting players.

Although the combination of affordable coffee, free internet, air-conditioned bistros, and many food options made for a killer combination, CCD needed to do more to differentiate itself. New competitors like Chaayos, Chai Point, and Blue Tokai entered and competed across price points.

CCD looked to consolidate its leadership.

The period of rapid network expansion was followed by a period of purging. The company started to shut down non-profitable stores to trim its losses. They realised that they had to change their strategy to fight competition.

In 2016, CCD started Cafe Concerts, which attracted a younger crowd. The concerts aimed at bringing some of the best young musical talent to perform at their bistros across the major metros.

The first concerts co-occurred in February across Mumbai, Pune, and Bengaluru.

1st Café Concert begins with a live gig by Ashish Noel performing at Café Coffee Day, Cunningham Road, BLR

The same year, CCD partnered with Freecharge, a financial services company, to encourage cashless outlet exchanges.

Their creative marketing and promotional strategies to drive sales were paying off, as CCD grew to INR 60 Cr in FY19 from INR 8 Cr in FY17.

But all was not well.

Total liabilities and debt had grown from 1,300 Cr in 2011 to 6,574 crore as of March 2019. Between 2014 and 2019, Siddhartha and CDEL promoter group’s four private holding companies pledged shares worth INR 3,522 Cr as security to raise these huge loans.

There was also an instance wherein the Income Tax department raided CDEL’s offices and uncovered concealed income of INR 650+ Cr.

Siddhartha was looking for ways to pay off some of the debt. He began by selling off 20.41% of his investment in Mindtree, making a profit of INR 2,858 Cr. There were also reports that Siddhartha was in talks with investors including Coca-Cola to sell part of his stake in CCD to bring down the debt. However, the company and Coca-Cola never confirmed those reports.

In January 2018, Café Coffee Day's share price touched an all-time high, taking the company's market capitalisation to more than $1Bn. However, the rising debt issue impacted the company's market valuation.

It would never touch that height again.

Pour Decisions

Like most pioneers of his ilk, Siddhartha was a natural risk-taker

Siddhartha was perennially searching for the next big thing. The flip side of this go-getter temperament was a predisposition to spread himself and his sprawling empire too thin.

In the process, Siddhartha racked up personal debt of INR ~1K Cr, over and above the corporate debt of INR 7K+ Cr, to fund the diversification.

To add to the capital-guzzling non-coffee businesses, the flagship cafes were not without their troubles.

7 years after setting foot in India, Starbucks was making its presence felt, having found a balance between its decadent drinks and the Indian palate. With its chic interiors, global appeal, and cultish following, it was priced at a premium of at least 50% to CCD.

On its part, CCD doubled down on affordable positioning, trying to counter Starbucks’ premium play with a volume-first strategy. It followed it up with an expansion spree, taking its store count beyond 1,700.

CCD had already set the base for Starbucks, making the latter's real estate decisions much easier.

Many of the outlets were now nearby, cannibalising each other’s business. Critically, with CCDs mushrooming everywhere, the aspirational value took a hit. The cool quotient, so integral to the modern-day café experience, was gone.

The coffee chain had missed a beat.

The Mindtree stake sale went through, but not without resistance from Mindtree’s promoters and an intervention yet again from tax authorities. The respite offered by the deal was only short-lived.

There was no end to Siddhartha’s battles with liquidity. And the battle scars were now hurting his pride and puncturing his spirit.

In a tragic turn of events, he died by suicide, acknowledging that he had failed to create a profitable business model despite all his efforts.

His demise opened a Pandora’s box for the company, with lenders queuing up to be repaid, investors selling their stakes in CDEL, and market regulator SEBI investigating for suspected fund diversion and lapses in corporate governance.

Covid further ravaged CCD’s cafés, kiosks, and vending machines in one fell swoop. Something had to give.

In December 2020, Malavika Hegde, the founder’s wife, became CEO to steady the ship and salvage the iconic brand.

Dark days had set in for the rising star.

Better Latte Than Never

The new management began in earnest.

It began by pulling the plug on non-core businesses, shutting down loss-making outlets, and bringing down debt to serviceable levels.

The 90-acre Global Village Tech Park was sold to Blackstone for INR 2,700 Cr. The group then transferred its broking and wealth management business to Shriram Credit for another INR 65 Cr.

Yes, CCD did wealth management and had a tech park.

The logistics arm was put on sale to cut down debt further. CCD’s store count dropped by more than half in the year ended March 2021.

As the pandemic abated, coffee chains in India found themselves at the intersection of revenge spending and an easy money regime.

Over two decades, CCD and later Starbucks established the archetype of spacious, air-conditioned cafés with elaborate menus, manned by friendly baristas operating exquisite equipment.

Third Wave Coffee and Blue Tokai filled in the void left by CCD’s diminishing presence and the trail left by Starbucks’ increasing footprint, as coffee startups raised $41.4M in 2022 alone.

The new-age coffee chains focused on smaller beverage sizes, localised food menus, and an astute store location strategy to go head-to-head with Starbucks. Multinational chains such as Tim Hortons and Reliance-backed Pret-a-Manger made belated entries into India.

On the other hand, CCD had its hands full managing the debt hangover and insolvency proceedings.

In January 2023, it came to light that multiple group entities had siphoned ~INR 3,500 Cr to a company fully owned by Siddhartha, unbeknownst to the board and untraced by auditors.

The funds were diverted, ostensibly to help the promoter repay personal debt taken to finance the group businesses. SEBI fined the listed company INR 26 Cr for the serious lapse in corporate governance.

Despite the legal troubles, the group managed to break free of most misfiring legacy businesses, cut the excesses in the café chain, and right-size its kiosk and vending machine footprint.

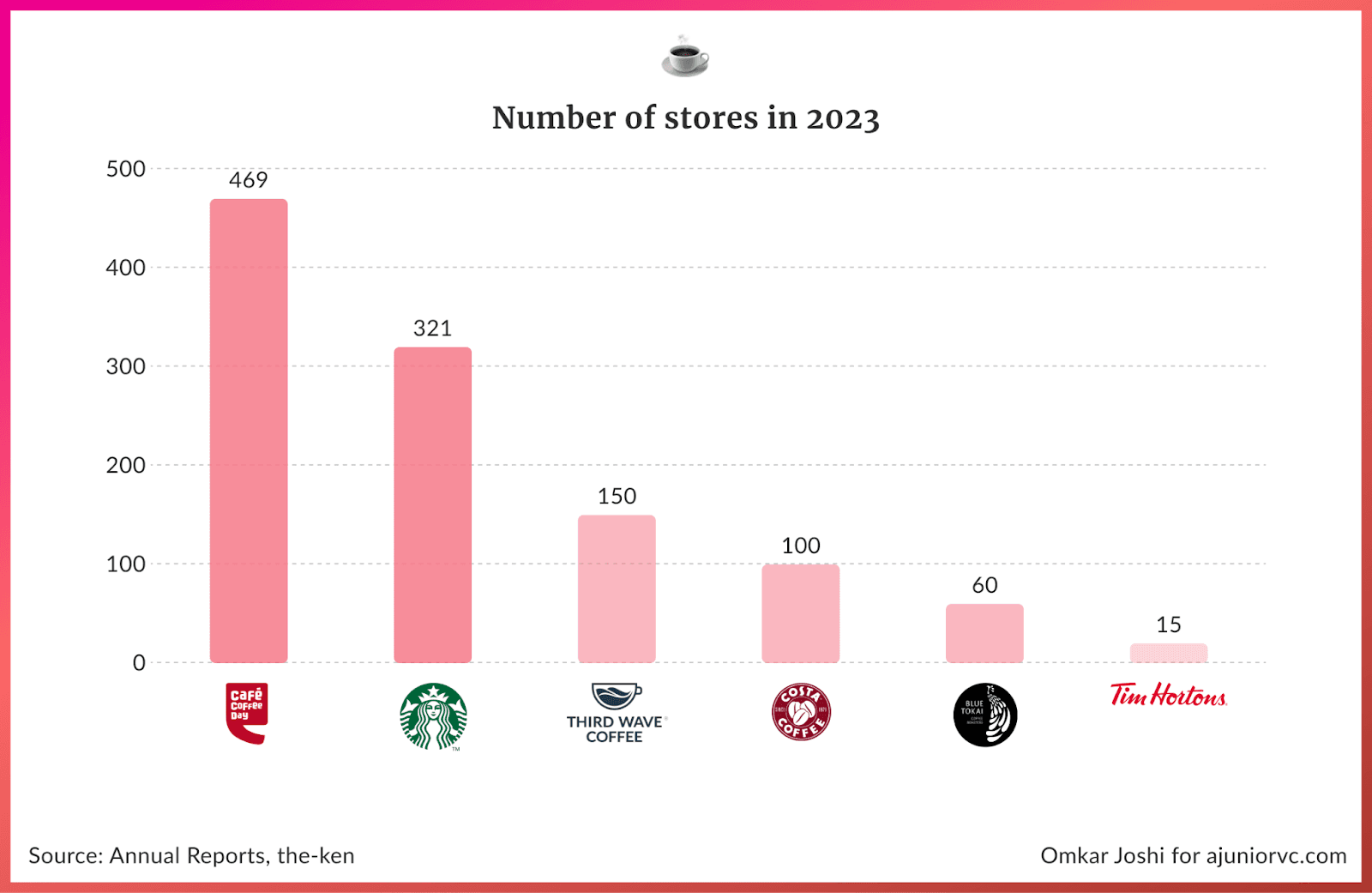

What remained after the cutting and chopping was still India’s largest café chain, with ~100 more outlets than Starbucks.

While insurgents and late-to-arrive heavyweights plan to expand aggressively, CCD’s unfinished turnaround gives it a massive head start.

Fourth Wave Coffee

A fourth wave of coffee is underway globally. The first wave was marked by instant, mass-produced coffee.

The second wave, led by Starbucks, was centred on coffee as an experience, making the café the ‘third place’ where people spent time after home and work.

The subsequent third wave emphasised a deep appreciation of flavors, characterized by coffeehouses brewing their specialty coffees.

The nascent fourth wave focuses on ethical sourcing and sustainability. with brands like Pret-a-Manger, known for 100% organically grown coffee and food prepared at onsite kitchens without additives.

The preference for sustainability challenges the ‘third place’ trope or coffee chains' expansive use of real estate. It also makes economic sense, given that none of them have a consistent track record of profitability despite achieving critical mass.

Parallelly, small-time players are experimenting with a takeaway-first strategy, wanting to make coffee a grab-and-go experience.

The strategy aims to replicate the success of Indonesia’s Kopi Kenangan, Singapore’s Flash Coffee, and the Philippines’ Pickup Coffee in turning coffee from an indulgent drink into a functional product.

Early adopters include Abcofee, which has 30 cafés in Mumbai and NCR. Some of them lack seating and operate like a reimagined chai tapri, but they offer a cappuccino comparable to that of Starbucks.

CCD could rise like a phoenix as this new wave kicks in. For almost four years, CCD has just been putting out fires, unable to do anything else.

From this fire, a phoenix could rise. Debt has fallen to 1,000 Cr from 7,000 Cr. The coffee business now drives 90% of the revenue. It is less sagged to move, more nimble, and focused.

Malavika Hegde had taken CCD alive.

CCD, by its kiosks and vending machines and its acquired nimbleness post-restructuring, could ride the new wave if it does take off. Similarly, it could pivot to becoming primarily a dispenser provider, taking a leaf from Chai Point.

Coffee connoisseurs would know that the production process involves grinding the bean before brewing. The grind, more than anything, determines the flavour of the coffee.

CCD has painfully endured the grind of business cycles over the past five years and more. Regardless of what follows, it now appears well-poised to return to full vigour.

Siddhartha’s original idea was to create a coffee culture in our tea-drinking country. His grand vision seems to have finally taken shape for all his flaws as a businessman.

In the almost thirty years of CCD's existence, India has grown from a coffee backwater to a 30,000 Cr market by 2026. CCD started the revolution, lost its pre-eminence, and is now back in the mix.

Its market cap has crept above 1,000 Cr, and is likely to keep moving northwards. If execution stayed the same way, it will see an expansion of multiple on revenue. It is already at 1,000 Cr, with a 3x multiple with cleaner books already putting it at ~3,000 Cr.

Paring debt and going with the growth of the market could see it climb back upwards of 5,000 Cr in market cap. The resilience of being in the market for three decades will only help.

It still has the largest number of stores, is still the second-largest chain by revenue, and has possibly the widest and deepest brand recall.

True to his tagline, a lot has indeed happened over coffee. As more continues to happen over coffee, CCD may very well remain at the forefront of it all.

Writing: Bhoomika, Abhinay, Anisha, Nikhil, Varun and Aviral Design: Omkar and Stability