Nov 27, 2022

Can India Convert 20 Years of Building to Be a Climate Superpower?

Electric Vehicles

Deep Tech

Climate

B2C

B2B

Technology

Last fortnight the COP27 was kicked off, and India became the highest-ranked big country on the global Climate Change Index.

An Atmospheric Discovery

In 1896, Svante Arrhenius demonstrated the relationship between CO2 and rising earth temperatures

Trying to work out why ice ages happened, Arrhenius’ seemingly strange conclusion was scoffed at. No matter, he won the Nobel prize for ionic solutions years later.

Arrhenius demonstrated that by burning fossil fuels such as coal, CO2 would be added to Earth's atmosphere, and humanity would raise the planet's average temperature.

This "greenhouse effect," as it later came to be called, was only one of many speculations about climate change and not the most plausible. Most people thought it was already obvious that puny humanity could never affect the vast global climate cycles governed by a benign "balance of nature."

In the 1950s, English steam engineer and amateur scientist Guy Stewart Callendar published arguments that greenhouse warming was underway. His claims provoked a few scientists to look into the question with far better techniques.

This research was made possible by a sharp increase in government funding, especially from military agencies that wanted to know more about the weather and geophysics. The new studies showed that CO2 might build up in the atmosphere and bring warming.

In 1960 measurements of the level of the gas in the atmosphere by Charles Keeling, drove home the point. The level was rising year by year.

During the next decade, a few scientists worked up simple models of the planet's climate system and turned up feedback that could make the system surprisingly sensitive. Others figured out ingenious ways to retrieve past temperatures by studying ancient pollen and fossil shells.

It appeared that grave climate change could happen, and in the past had happened, within as little as a century or two. Calculations made in the late 1960s suggested that as CO2 built up in the atmosphere in the next century, average temperatures would rise a few degrees. But the models were preliminary, and the 21st century seemed far away.

In the early 1970s, the rise of environmentalism raised public doubts about the benefits of any human activity for the planet. Curiosity about climate change turned into anxious concern. A few degrees of warming no longer sounded benign, and as scientists looked into possible impacts, they noticed alarming possibilities of rising sea levels and possible damage to agriculture.

Concentration curves for atmospheric CO2 became one of the major icons of greenhouse effect warming. The curves showed a downward trend of global annual temperature from the 1940s to the 1970's stoking fears of the return of the ice age.

As the scientific world began to fear the large-scale impact of human growth, change began in a recently independent South Asian nation.

Promising Indian Energy

Indian environmentalism started, and majorly was, about social justice.

Although an important thread in the wider discourse, wilderness advocacy and the sentiment about ‘‘protecting the environment” has never been the defining feature of Indian environmentalism.

Instead, the relationship between environmental change and social and economic inequality unified various environmental movements.

The origin of The Energy Research Institute (TERI) is a perfect example of how economic insecurity fostered environmentalism.

TERI was founded in 1974 at the invitation of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. At the time of its founding, it was referred to as the Tata Energy Research Institute.

The inspiration for its founding came from a Tata engineer Darbari Seth, who was concerned about the enormous quantities of energy his factory spent on desalination. He proposed the idea of a research institute to tackle the depletion of natural resources and energy scarcity. TERI was set up with a corpus of INR 3.5 crore with the blessing of Tata Chairman J.R.D Tata.

As TERI was being set up, another grassroots movement focused on trees was taking off.

The Chipko movement was grounded in the need for social and economic equality leading to a movement around environmental justice. The Chipko movement was a nonviolent social and ecological movement by villagers.

The movement began in the 1970s in response to the increasing destruction of forests for commerce and industry. When government-controlled exploitation of natural resources started to threaten villagers' livelihoods, they sought to stop the destruction.

The movement spread throughout the country, becoming an organised campaign. The movement got its name from protesters hugging trees to protect them from loggers. The movement spread throughout India while staying largely local and organised autonomously.

Environmental governance also began to pick up.

As Indira Gandhi returned from the United Nations (UN) Conference on Human, Environment and Development in Stockholm in 1972, the environment was now a global issue.

This was the first world conference to sign a Declaration to prioritise environmental issues.

Post the Declaration, Indira Gandhi’s government set up a National Environmental Planning and Coordination Committee.

Additionally, in 1972, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) was set up, followed by the state boards. The department of environment came into existence on November 1, 1980, followed by state departments. Environmental laws on water (1974), air (1981) and forest conservation (1981) were passed, as also the umbrella act of Environment Protection (1986).

All in all, there was a huge push towards nature conversation and awakening the importance of nature.

Climate change emerged as an issue for Indian policy-makers in the late 1980s when the Indian government began transitioning to a market-oriented economy to accelerate growth and reduce poverty.

This coincided with the growing recognition of climate change globally, as indicated by the formation of a massive global body

Climate of Fear

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was formed in 1988.

The IPCC is a body of the United Nations responsible for advancing knowledge on human-induced climate change. A big, publicized change was the depletion of the Ozone Layer.

The Ozone Layer, a protective layer against ultraviolet radiation, was found to be depleting. An international treaty that ratified the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer was signed in 1987

The protocol was aimed to regulate the production and use of chemicals that contribute to the depletion of Earth’s ozone layer. Initially signed by 46 countries, the treaty now has nearly 200 signatories.

This was a massive coordinated effort.

The initial agreement was designed to reduce the production and consumption of several types of chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) and halons to 80% of 1986 levels by 1994 and 50% of 1986 levels by 1999. The protocol went into effect on January 1, 1989.

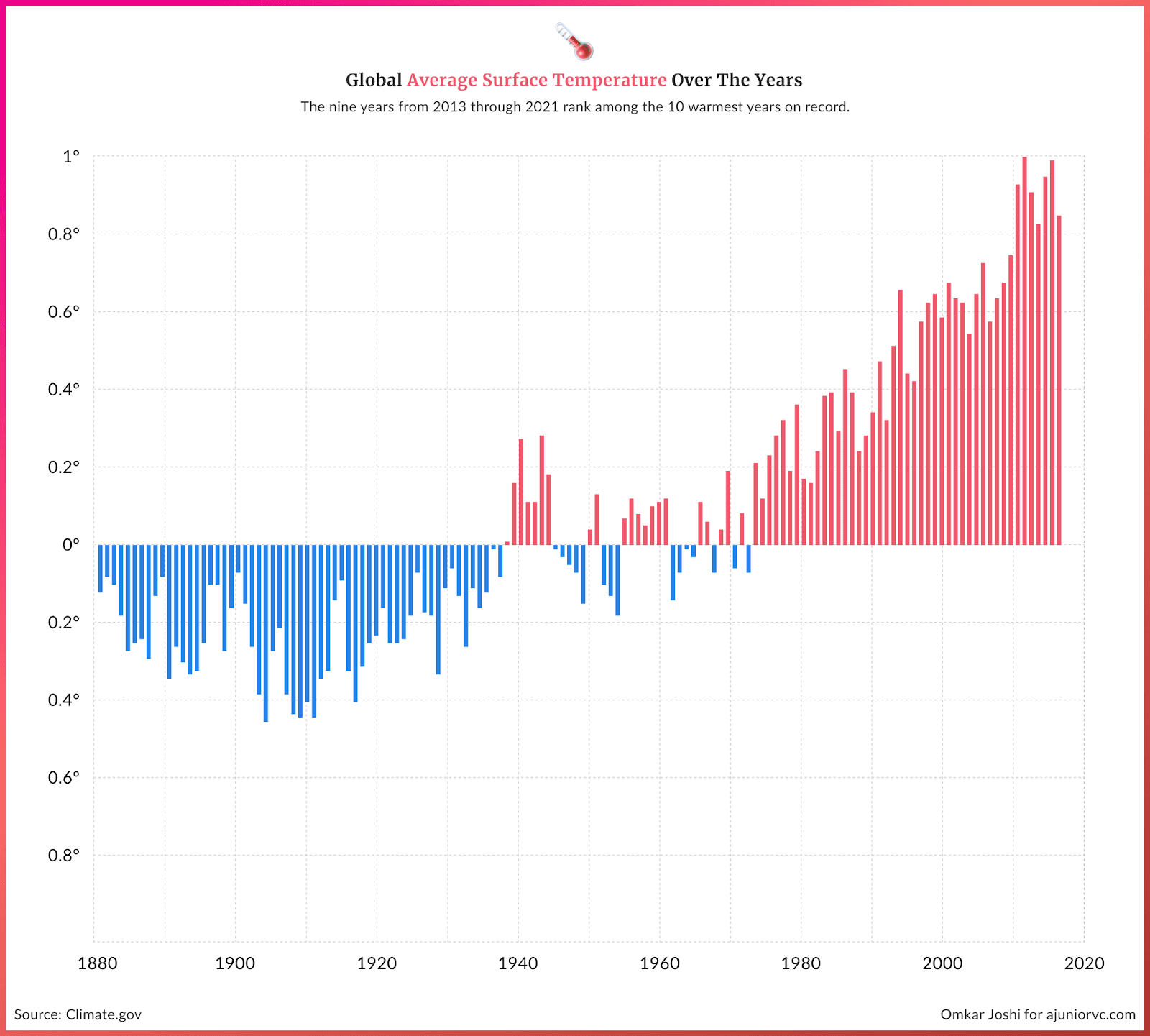

By then, the rapidly increasing surface temperature was becoming awfully clear.

In 1988, the term ‘Global Warming’ hit the front pages.

This was based on the testimony of NASA climate scientist James Hansen and the startling research findings he delivered to the U.S. Senate.

On June 23, 1988, as the temperature in Washington rose to nearly 100 degrees Fahrenheit, Hansen made the most emphatic and widely publicised case for alarm.

The media and the public took notice of the moment's literal heat.

The rest of the summer offered up some of the worst heat waves in the US. Drought conditions parched 40 states.

Leaders worldwide began to notice: An Environment Policy and Strategy Statement was issued during the UN Conference on Environment and Development in 1992.

The IPCC released climate change reports in 1992 and 1996. Questions from scientists caused IPCC to review their initial data on global warming, but this did not make them reconsider whether the trend exists.

We now know that 1998 was globally the warmest year on record. It also became clear that climate change was a global problem that is hard to solve by single countries.

This was a hallmark of managing climate change. Therefore in 1998, the Kyoto Protocol was negotiated in Kyoto, Japan.

It required participating countries to reduce their anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions by at least 5% below 1990 levels in the commitment period 2008 to 2012.

The Kyoto Protocol was eventually signed in Bonn in 2001 by 186 countries. This was one of the largest efforts of the last two decades. Several countries, such as the United States and Australia, retreated.

India played a major role at COP 1 in Berlin in 1995, submitting a proposal for a 20% emission reduction by industrialised countries in 2000 compared to 1990. India’s watered-down version ultimately became the Kyoto Protocol.

But India was in deep water itself.

Bad Indian Weather

By the end of the 90s, India’s woeful environmental situation was crystallising.

it had become increasingly evident that India’s economic policies had a devastating environmental impact. This was, by extension, on the livelihoods of people.

The government’s statistics collected around the turn of the century painted a dismal picture.

They claimed that soil erosion, water-logging, and salinity affected 60% of cultivated land. The average annual per capita water availability had declined by almost 70% in the first five decades of the post-independence era. The area under forest cover, at 19%, was well below the desired level of 33%.

Crucially, each of these numbers had a social justice dimension.

Adverse ecological changes tend to exacerbate poverty by directly impacting poor people dependent upon ecosystem services.

Environment Impact Assessment for 32 sectors became compulsory. Environment approval committees were formed for each sectoral assessment, and all power was vested with the Centre.

By 1999, India became a nation to follow the environmental governance system with further controlling notifications on coastal zone management, hill development, and disposal of wastes.

By 2001, it was much more likely than not, the panel announced, that our civilisation was headed for severe global warming. At that point, the discovery of global warming was essentially completed.

What brought us to this point?

The 20th Century was marked by significant economic progress. Global GDP doubled four times and then some in the last century.

In no previous century had the global GDP even doubled before. The human population came within a whisker of doubling twice during the last century. In no previous century had the human population doubled before.

The increased prosperity and population growth meant a huge energy demand.

Human beings initially used physical labour as a source of energy. Discovering animals, then wood, the search for the most optimal energy source was afoot.

The discovery of coal started humanity’s population explosion and climate change. The trouble was that nobody accounted for the “cost” of burning carbon because it was such a good energy source.

That explosion of fossil-fuel use is inseparable from everything else, making the 20th century unique in human history. As well as providing unprecedented access to energy for manufacturing, heating and transport, fossil fuels also made almost all the Earth’s other resources vastly more accessible.

The nitrogen-based explosives and fertilisers that fossil fuels made cheap and plentiful transformed mining, warfare and farming. Oil refineries poured forth the raw materials for plastics. The forests met the chainsaw.

All of this meant carbon stored up in the crust over hundreds of millions of years was being released in a few generations

Developed countries had already got ahead, and developing countries like India needed to act.

Winds of Change

India’s early foray into renewable energy in the early 2000s would be led by ‘India’s Wind Man’ Tulsi Tanti

Tanti started Suzlon to provide energy to his textile business after noticing an irregular supply of electricity locally and increasing costs which did no good to the profits of a business with high energy needs.

Later, in 2001, he sold the textile business to focus solely on building the renewable energy upstart.

In the first few years of the decade, Suzlon multiplied. Building in India, it became a pioneer of wind energy globally. It soon started offices in the US, Germany and China.

By 2005, Suzlon had scaled so rapidly that it went public. It truly was the first Indian company to go green and make a business in the process. It reported 3,000 Cr of revenue, becoming a darling of investors in more ways than one.

At the same time, the countries relying on Suzlon were finally starting to see the Kyoto Protocol come into effect in 2005.

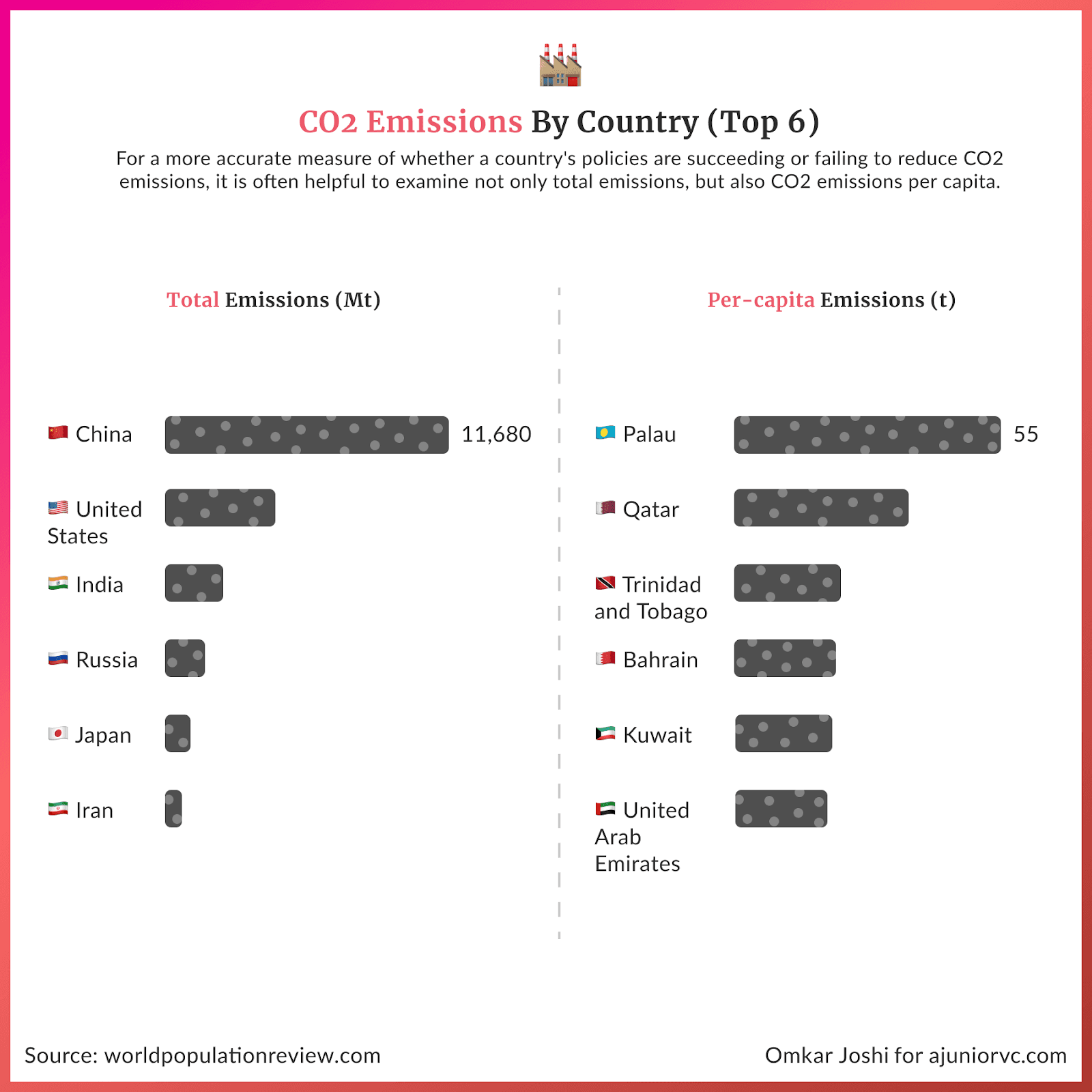

Despite the protocol, the two largest emitters - the United States and China were responsible for enough emissions to make the reduction caused by 150+ countries who signed it seem insignificant.

China overtook the US in 2006 as the biggest emitter of CO2 (~20%) and has continued the trend ever since. It ratified the Kyoto Protocol, but as a party without binding targets.

Despite the alarming rise in the effects of climate change globally, the anti-climate change lobbying grew, with the top 5 spending a whopping $200Mn/year on it. It is estimated that they alone were responsible for 1/10th of the total CO2 emissions.

Despite all of these events, one of the major successes was the Montreal Protocol, which was the ban on Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) worldwide.

By 2007, it showed how long-term global coordination has averted a major climate catastrophe. It was called “the single most successful international agreement”.

India was no stranger to the rapid developments in climate change. By sheer virtue of its population and economic size, it was becoming a big emitter.

In 2008, the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) was released by the Prime Minister with eight missions for ensuring the country's economic sustainability.

Between 2000 to 2010, global emissions soared by 32%. India’s emissions grew from ~3% to ~5% each year during the ‘00-‘10 decade.

The growth was driven by increasing electricity demand, infrastructure and manufacturing growth.

India stood as the third country in emissions worldwide, but change was afoot.

Its Always Sunny in Porbandar

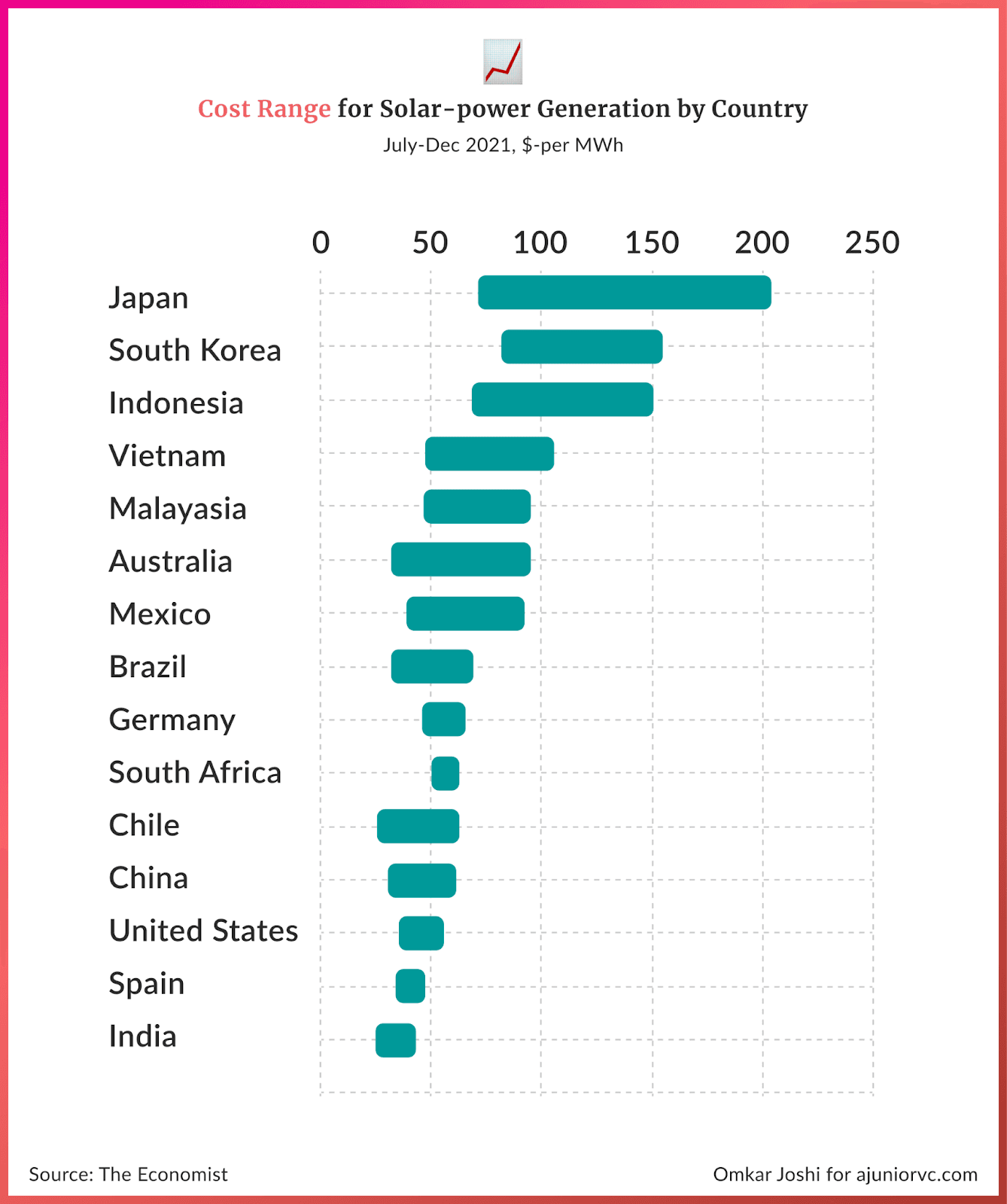

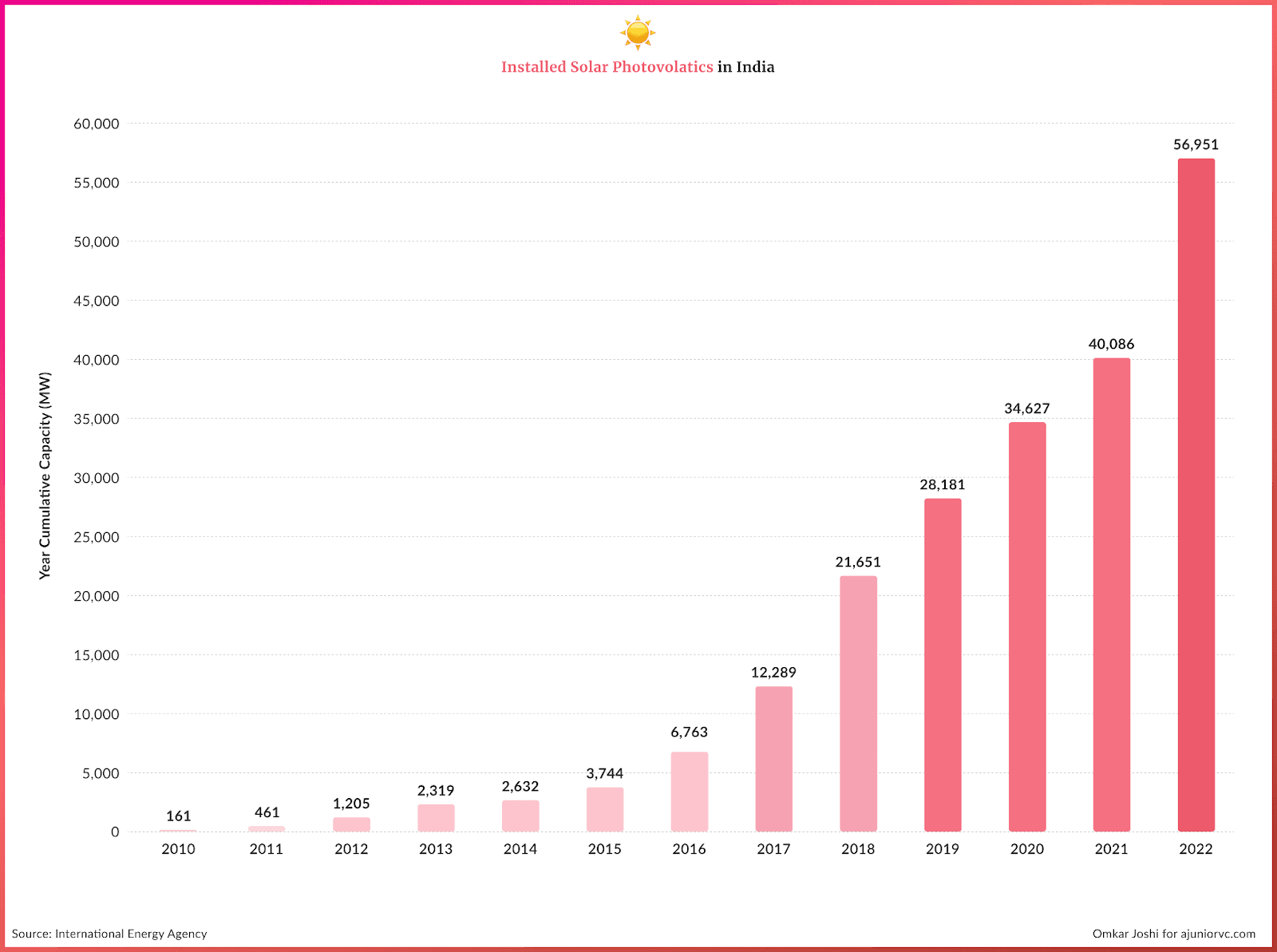

By 2011, solar energy was becoming a major pillar in India’s transition to renewables.

The Government launched the National Solar Mission. India had a huge solar energy potential with nearly 5,000 trillion kWh per year energy incident over India's land area.

Given its potential to fulfil the country’s energy demands since it is abundant and most secure of all other sources, This target was to install 100 GW grid-connected solar power plants in a decade.

In 2013, India’s installed capacity was less than 3 GW, signalling how ambitious this target was.

Indian entrepreneurs started entering this space to make renewable energy more affordable and available at a larger scale which was needed to achieve India’s ambitions in this space.

In 2015, the Adani group established Adani Green Energy. Reliance followed suit in 2016, starting its own Green Energy enterprise. Both had solar at their core.

India was falling short of the target set with only about 2 GW capacity added, bringing the total solar capacity to less than 4 GW.

In 2017, the World Bank also started supporting Government’s efforts by providing $100 million in concessional finance, which helped develop two large solar parks in Madhya Pradesh and the infrastructure to connect them to the grid and distribute power to consumers.

One of these was the Rewa Solar Park which established a record-low tariff for renewable energy, less than 5 cents per kilowatt hour.

India’s solar journey gained momentum after signing the Paris Climate Agreement late that year. It underlined India’s commitment to clean energy, facilitated international knowledge exchange and transitioned to flexible power purchase agreements.

In just 6 years, India has increased energy capacity through solar to 10x, from 6Gw in 2016 to 60 Gw in 2022, shy of its initial ambitious target of 100 Gw.

Bhadla Solar park in Rajasthan would become the biggest solar park in the world with a total capacity of 2245 Mw and spawning over an area of 14000 acres, producing electricity at Rs 3 per kWh.

In 2019, Adani Green Energy won one of the world’s largest solar contract from Solar Energy Corporation of India to develop 8 GW of solar projects. This was along with a commitment to establish 2 GW of additional solar cell and module manufacturing capacity at the cost of ₹45,000 crores or $6 billion, creating 4 lakh direct and indirect jobs.

Soon, Prime Minister Narendra Modi conceptualised One Sun, One World, One Grid (OSOWOG) for developing a globally interconnected solar grid. OSOWOG is an innovative solution to the limited daytime availability of solar power, thereby reducing the downtime of solar power systems.

Solar generation capacity increased 50-fold since 2012, to nearly 50GW at the of 2021.

As India’s solar grid took off, another grid was getting built on the roads.

Electric Dreams

By 2021, 1 in 125 vehicles on the Indian roads was an Electric Vehicle (EV), mostly two-wheelers and three-wheelers

In the same year, a production-linked incentive scheme for the automotive sector was approved by Cabinet to boost the manufacturing of electric vehicles and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles.

We had covered the history of electric vehicles, and how it was more than a fad.

The EV story picked up even faster as the pandemic started to recede.

Policy changes made it more favourable for EV manufacturing. This increased push to improve charging infrastructure, changes in technology decreasing the total cost of ownership of vehicles and adoption of full-stack approach companies going beyond manufacturing and distribution, selling directly to consumers, setting up charging infrastructure and providing financing options.

This is key to accelerating initial adoption as customers are assured of charging infrastructure support and financing by companies are the reasons for the increasing adoption of EVs in India.

India reported sales of 277,910 electric two-wheelers in the April-September 2022 period, a 404% increase over the same period last year which saw 55,147 units sold.

EVs saw many startups coming up with Ather and Ola Electric the big gorillas.

Ather Energy raised $50 million in 2022, valuing them at $700-800 million. It setup manufacturing facilities in 2 locations and offers sustainable mobility and energy infrastructure solutions. Ather manufactures two-wheeler electric vehicles, 450X and 450 Plus, sold on its website and offline retail stores.

In 2022, Ola Electric announced that they clocked 20,000 sales figures in a single month, the highest ever from any electric vehicle manufacturer in India.

Ola Electric offered two-wheelers EVs and energy infrastructure. Its EV startup manufacturing facility, Ola Future Factory, has a production capacity of 10 Mn two-wheeler EVs per annum. It claims to have sold EV scooters worth $150 Mn to date

Though India hasn’t pledged to phase out conventionally fueled vehicles by a certain year, it has an ambitious target to have 30% of all new vehicle sales be electric by 2030.

This could allow India to save on crude oil imports worth over $14 billion annually. The Indian government has allocated $96.8 million to a scheme, FAME- Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles in India and has introduced several supplies and demand-side incentives to facilitate the switch to EVs.

Some states have also set ambitious EV targets. 18 out of 28 states have either a draft policy in place or have already notified one.

EVs would only be one of the big pieces in the renewable puzzle.

Rising Renewables

By 2022, India continued to be the world's third biggest emitter of carbon dioxide after China and the US.

But its huge population means its emissions per capita are much lower than other major world economies. India emitted 1.9 tonnes of CO2 per head of population, compared with 15.5 tonnes for the US and 12.5 tonnes for Russia.

But it still does not take away the large-scale impact of climate change.

Loss and damage due to climate change can cost developing countries like India over 400bn$ by 2030 and over 1tn$ by 2050. As an example of the financial cost of damage caused by extreme weather events linked to climate change, the extreme flooding in Pakistan in 2022 is estimated to have caused losses costing up to US$40 billion dollars.

Reducing emissions is not the only goal to overhaul India’s energy system.

It’s also cheaper and the government wants to decrease its dependence on oil, which it is one of the biggest importers of. Around three-quarters of oil is imported.

It will also help reduce air pollution, reportedly around 1mn people die cause of air pollution in India.

The average fuel-only cost for producing electricity by burning coal in India in 2022 is as high as $127 per megawatt hour (Rs. 10.4 per unit) compared with around $30-35/mWh for new onshore wind and solar projects.

Due to India’s huge push on Solar, power tariffs have fallen massively, going as low as 29$ per Mwh (Rs. 2.5 per unit(Kwh). Even if government subsidy is removed the cost comes out to be around the cheapest in the world, less than 70$ per MWh.

Comparing the cost of wind and solar, coal power is the most expensive. Nuclear power is affordable, little south of Rs 3 per unit, but it has political challenges.

Currently, Hydropower contributes the most in terms of installed capacity for team renewables, the cost for hydro energy comes around to 5-6 rupees per unit of electricity.

Renewable power is growing very fast in India.

Indeed, renewables have already supplanted coal when it comes to building new generating capacity.

Besides the investments driven to expand the infrastructure of renewables to tackle climate change, India has come up with innovative solutions to prevent climate change like solar financing and carbon accounting.

Carbon accounting is the process by which organizations quantify their Greenhouse gas(GHG) emissions, so that they may understand their climate impact and set goals to limit their emissions.

One carbon credit unit refers to one tonne of CO2 mitigated and is denoted as a Certified Emission Reduction (CER) certificate. Carbon credits are an incentive given to an industrial undertaking for the reduction of the emission of GHGs.

India Inc has begun to recognise the importance of carbon accounting.

It has undertaken and reported this in various public forums such as Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) and “sustainability reports”.

India’s growth in renewables on a global scale is starting to get noticed.

With Great Power Come Great Economies

COP26, the UN Climate change conference in Glasgow was held in the winter of 2021

It brought together 120 world leaders to accelerate on the plans made to curtail the effect of climate change. Countries reaffirmed the Paris Agreement goal of limiting the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C.

At the conference, India announced it would reach the net zero emission target by 2070 against the proposed 2050. It would also reach 500GW of non-fossil energy capacity by 2030, increasing its energy supply from renewables to 50% of the total and reducing 1 billion tonnes of carbon emission from now to 2030.

This is an absolute transformation for a country of such scale and growth.

India plans to achieve the 500GW goal of non-fossil energy production. This would be driven majorly through solar of around 300 Gw, which is expected to contribute to around 60% of this increase.

It’s expected to cost $500B to achieve the renewable dream. A big share of this has been pledged by current fossil behemoths Ambani and Adani.

Adani, in partnership with the Rajasthan government, is setting up a 10,000 Mw solar park, which will be the largest integrated facility in India. The investment is 60,000 crores in the park.

Ambani’s Reliance plans to spend $80bn on clean energy in India. Reliance, like Adani Group, has made a fortune from fossil fuels. But as it is clear, this is an energy play.

It is now developing a clean-energy cluster in Jamnagar, another port in Gujarat, which also houses the firm’s massive petrochemicals complex. They plan to build 20 Gw of solar generation capacity by 2025.

Reliance also announced a new Giga factory for power electronics. Observing that one of the key components linking the entire value chain of green energy is affordable and reliable power electronics.

They are also investing in producing affordable green hydrogen, getting it under 1$.

Green Hydrogen can save 830M tonnes of CO2 annually when this gas is emitted from fossil fuels. The main reason for the low usage of green hydrogen is the high cost, which Reliance is looking to solve.

India recently announced that Gujarat will become the world's biggest hydrogen hub.

It is not just India’s behemoths embracing Mr Modi’s green vision, smaller companies are investing heavily, too.

Greenko, for instance, is building the world’s biggest network of grid-scale energy storage using a technology called pumped hydro. They want to build a nationwide, grid-connected “energy-storage cloud” akin to Amazon’s data cloud.

Indian Oil is also looking to enter the green hydrogen business, it plans to invest 25B$ in cleaner alternatives to become net zero by the year 2047. It partnered with ReNew, a renewable energy firm, to produce green hydrogen.

India’s green-hydrogen firms are even venturing abroad. Acme Cleantech Solutions, a solar-generation pioneer, has pivoted to making clean fuels. Together with Scatec, a Norwegian clean-energy firm, it is investing over $6bn to produce green ammonia

It is hardly surprising, then, that climate tech is at a tipping point.

The range of solutions that are good for the planet and good for the bottom line is growing every day – electric mobility and renewable energy are already going mainstream. We are starting to see commensurate momentum globally in financing climate interventions.

Various innovative startups working on climate tech are starting across the country. Breathe and Carboncraft is working to decarbonise the atmosphere.

For widespread accessibility of electric vehicles, affordability and efficiency will be key, Cygni is building low-cost customised Li-ion batteries. Gegadyne has developed a nano-tech-based battery with a longer life cycle, higher energy density and faster charging. Nexus Power manufactures biodegradable batteries, made from unburnt crops, to power EVs.

Clean mobility has attracted multiple homegrown enterprises eager to replicate the success of Tesla, OlaElectric and Ather have come out on top.

Blu and Yulu have chosen different paths to their idea of sustainable mobility. Eplane.ai is building an electric flying taxi and Navalt is an indigenous eco-marine tech company, building solar electric vessels for marine transport.

India’s push has borne fruit, ranked the highest for a large country in the global climate index.

India’s bids of 20GW of clean energy last year are the highest in the world, 5x that of the US.

Led by large conglomerates, and a strong government push, India has been building quietly for 20 years. With upstarts in the mix, the story is getting even better.

As the world fights climate change, India is a dark horse emerging from the shadows to become a climate superpower.

Writing: Abhinav, Ritika, Tanish, Varun and Aviral Design: Omkar and Saumya