Jan 23, 2022

Are Electric Vehicles India’s Future or Premature Fad?

Electric Vehicles

Technology

Brand

Series E-G

B2C

Transportation

Last fortnight, Ather Energy raised $60M in its newest round, as Tesla got courted by Indian states to set up a manufacturing plant

Lighting the Dimming Electric Vehicle Bulb

In 1884, a young Serbian American Engineer by the name of Nikola Tesla arrived in New York City to collaborate with Thomas Edison to develop commercial electricity.

Although Tesla was successful in his attempt, due to a series of tragic events, he died a poor man in 1943.

Little did he know that he would propel into motion a series of events that would lead to the birth of a whole new sector. His name would fittingly re-emerge

Time seems to have its own justice arc.

The birth of Electric vehicles, however, cannot be attributed to one person, it is rather a series of contributions from innovators in Hungary, the Netherlands and the United States that led to its inception.

Contrary to perceptions, as early as 1900, electric cars were enjoying massive adoption in the US, accounting for around a third of all vehicles on the road. People like Henry Ford and Thomas Edison also threw their weight behind electric vehicles, seeing the promise that they hold.

However, it was Henry’s famous gasoline-powered Model-T that dealt a blow to the electric car.

It made gasoline-powered cars widely available and affordable. For context, in 1912, the gasoline car cost only $650, while an electric roadster sold for a whopping $1,750

Tellingly, electric cars started to perish from the market and witnessed a ‘Kodak moment’, being replaced by cheap gasoline-powered cars.

Almost a hundred years later, the pendulum would start swinging back. E-vehicles began to re-emerge ‘Undertaker style’ due to soaring oil prices and widely resonating environmental concerns.

The bearings of this would have an impact halfway around the world. In India, a quiet electric revolution started to take shape.

In 1996, India got its first electric vehicle in the form of a three-wheeler called Vikram SAFA. It was developed by Scooters India in Lucknow and operated a 72-volt lead-acid battery,

Approximately 400 vehicles were made and sold.

In 2000, the Indian electrical behemoth BHEL (Bharat Heavy Electronics Limited) would follow suit and launch an 18 seater E-bus. It had an AC induction motor and a 96V lead-acid battery pack as its power source.

Around 200 electric vans were created and operated in Delhi.

However, these vehicles ran into issues due to their lack of consistency, short battery life, and extremely high battery costs.

India's thirst to witness a commercially successful electric vehicle would take some time to quench.

An Indian Pioneer Discovers Global Potential

In 1999, Chetan Maini, a Stanford grad, would return to India to chase his dream of building India’s first electric car.

As a student, he had won the top prize for building a solar-powered car for a race. Ever since then, he had been fascinated by alternative fuels for automobiles and had been tinkering if he could build something for India.

After 7 years of hard work, Chetan launched India’s first electric car in 2001 and named it ‘Reva’, after his mother, which meant a new beginning’ in Sanskrit.

REVA was an acronym for "Revolutionary Electric Vehicle Alternative”.

With its sleek design and performance, the car was a resounding success. However, the challenges he faced were enormous.

With a nonexistent VC ecosystem at the time, he had to find funding from traditional sources like the ICICI bank and the Indian Government’s technology development board.

Chetan realized very early on that in a new market like EVs, building good products was not everything, he had to market and educate customers as well.

However, just one month after Reva’s launch, the government doubled taxes for electric cars and removed all subsidies.

With no funds left for marketing, they decided to go fully online and sell in countries like the UK. To their surprise, sales in the UK picked up and outperformed India.

Reva would go on to become one of the best-selling cars in the world, being sold in almost 24 countries.

It is interesting to note that Reva was launched 7 years before Tesla’s roadster and at 10% of its cost.

As global developments started to pave a road toward a bright, clean future, Reva gained the attention of investors and corporations.

It would go on to be acquired by the Mahindra Group, being marketed as M&M Reva.

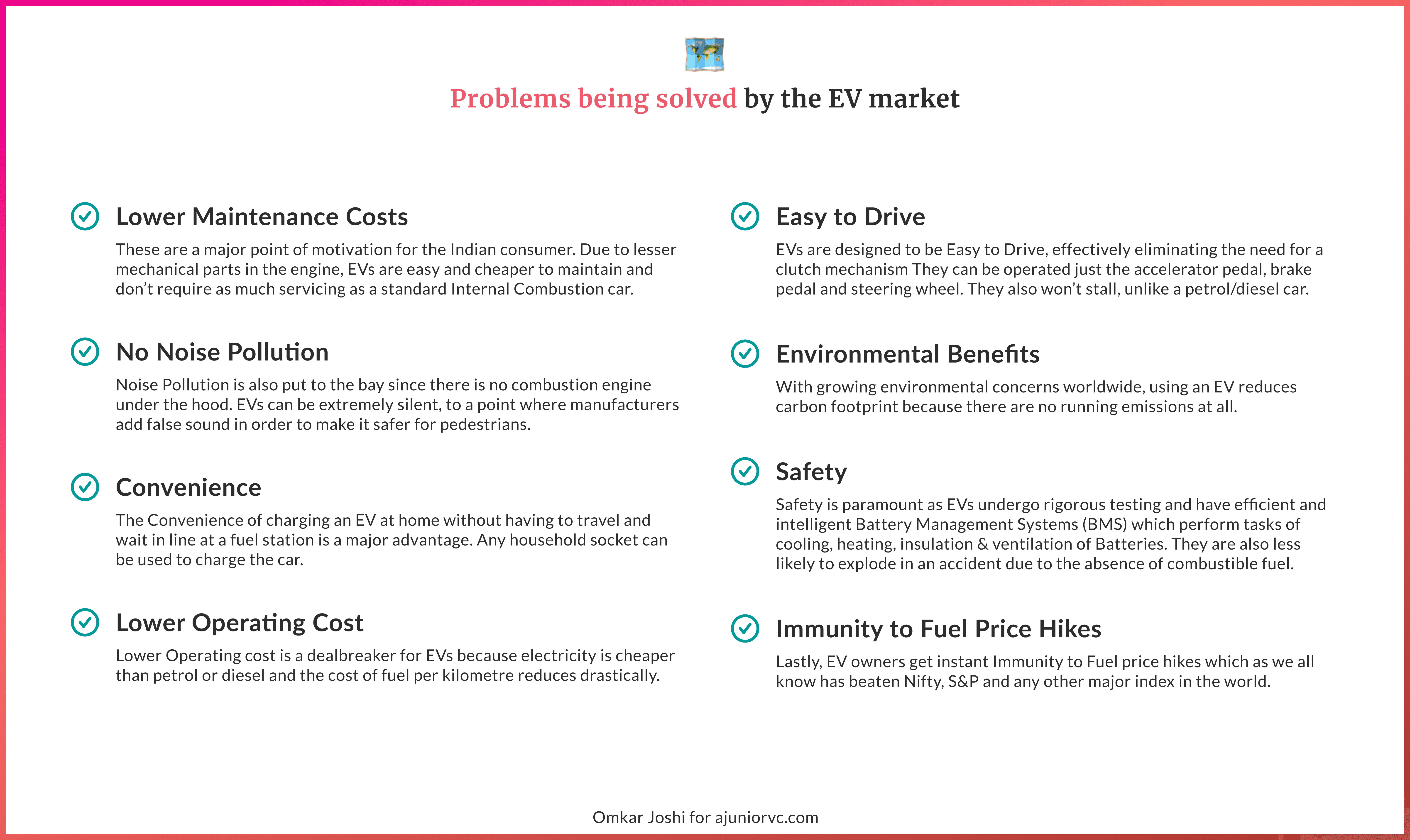

With the Indian EV industry being catalyzed by REVA, a few clear problems that the market was solving started to emerge.

With a laser focus on the points mentioned above, the EV industry was getting charged up slowly but steadily.

Sparking the Indian Market

As India entered 2000, a rapid acceleration in technology could be seen globally.

One particular area where major changes were happening was in the development of the Lithium-Ion battery, the heart of an EV.

Surprisingly, these batteries were being rapidly researched on and developed by an unlikely suspect, the phone manufacturers.

While Sony pioneered the first Lithium-Ion battery for commercial use in a Handycam, Motorola helped make them lightweight for use in their phones.

The Lithium-Ion battery would even go on to power the first iPhone

The early 2000s innovation in the Lithium-Ion battery was a significant inflection point that led the EV industry to scale up.

With the onset of globalization in India, the doors to the transfer of technology and knowledge from around the world were now wide open.

By 2005, around 200 dealers and 55 traders had entered the Indian EV market, particularly around the 2 wheeler segment.

But, most of these traders just sold and forgot about the 2 wheelers. Lack of maintenance and services coupled with poor battery quality spelled disaster for the entire industry.

India needed a heroic effort to bring customer trust back to the Industry. Who better to do it than one of India’s largest and most trusted 2 wheeler manufacturers, Hero cycles.

Between 2006 and 2007, global demand for the 2 wheelers segment was growing the fastest in the EV pie, at a whopping 18% CAGR.

To add to this, 2 wheeler EVs had the lowest cost of ownership and economics of operation in the entire EV industry, making it a perfect fit for price-sensitive Indian customers.

Hero was staring at a massive 2 wheeler EV opportunity in India, ripe for the taking.

In 2007, Hero cycles, in partnership with UK-based ULTRA Motor, launched a series of 2 wheeler bikes. These electric bikes became popular among other companies as well.

Renowned bike manufacturers like Electrotherm India, TVS Motor and Hero Electric (earlier Hero Ultra) were some companies that started to build these electric bikes at scale.

These players entering the market saw an influx of reliable products and robust maintenance schemes.

Customers started to trust electric vehicles again.

While the EV market started to heat up with players, the pace of product development and tech acceleration was still slow.

Most players had no R&D of their own, relying heavily on importing battery tech from abroad. To add to that, the Indian customer expected durability, reliability, and good mileage at ridiculously low costs.

This paired with almost nil involvement from the government in terms of subsidies or infra didn’t bode well for a nascent Industry trying to break out on its own.

To catalyze the market, the solution was to build the backbone infrastructure and offer the right incentives. Customers had to be encouraged to go from ‘Kitna deti hai’ to ‘Ek Charge mai kitna chalti hai’!

While the hype cycle had begun in earnest, there were clear problems that seemed insurmountable in the near term.

Energy Losing Range

As India entered 2010, the challenges for EV adoption were everywhere.

However, these challenges were much tougher to solve in India. The largest challenge on the consumer side was range anxiety.

Range anxiety was the fear that EV owners that the charge on their battery may not be enough to take them to their destination. ICE vehicle owners did not suffer range anxiety due to the availability of fuel stations at close distances.

The range anxiety issue was solved by a combination of two factors: adequate charging infrastructure and higher battery capacity on a complete charge.

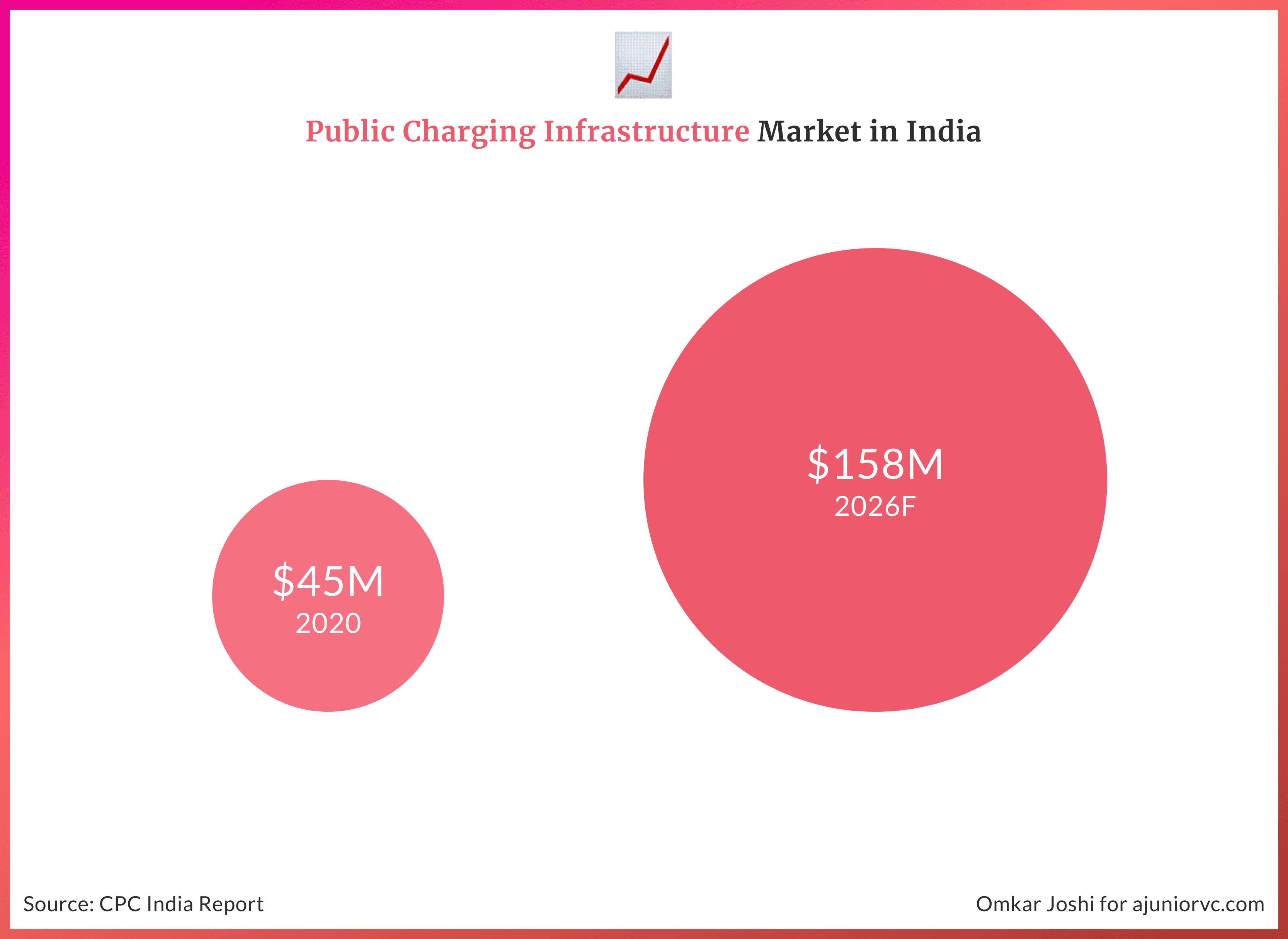

But setting up charging infrastructure itself was a challenge

It required space which was at a premium especially in urban cities. The real-estate costs were high. EVs required time for charging which increased the parking fee for EV owners.

In addition, the high investment required for transmission lines, power distribution centers was also a constraint. The cost of charging equipment and installation varies on the level and type of the charging infrastructure i.e. fast, medium, or slow charging.

By 2012, the total initial cost of setting up a charging station was quite high. The infrastructural costs were estimated to be around 20 lakhs, with another 14 lakhs as charger costs, depending on the type of charger.

Public infrastructure was needed to have fast chargers which are the most expensive. The problem is also further compounded as there was a lack of trained manpower to operate the equipment

Battery swapping had the potential to address challenges like high battery replacement costs, the initial cost of acquisition, long charging duration, and insufficient charging infrastructure.

A quick interchange station required much lesser space as compared to a charging station. The process of battery swapping could be faster than refueling IC engines. In addition, the energy infrastructure companies owned the batteries and not the vehicle owners which decreased the initial cost of the vehicle for the owner.

However, for efficient use across providers, batteries had to be made to common standards and specifications which is another challenge in itself.

By the time India entered 2014, the number of charging stations could be counted on your fingers. The number of public charging stations all across the world was in the thousands.

Indian EV was in the trough of disillusionment, and it was going to stay there if nothing change.

The ecosystem would have to play together to win big in the myriad complexities of EV. The massive size of India, with a vehicular base

Two Wheelers Make a Power Play

By 2015, India had become a unique market when it came to vehicle ownership.

Car ownership was very low with 22 cars per 1000 people, while two-wheeler ownership was among the highest globally with more than 200 per 1000 people.

Two-wheelers and three-wheelers played a significant role in the last mile mobility in India. Seeing this structure, a tiny startup called Ather Energy started to build an electric 2 wheeler from scratch.

It was betting that the penetration of electric two-wheelers was expected to reach up to 12% in 10 years, from virtually nothing.

From a two-wheelers perspective, people would primarily use it for local, short-distance travel and deliveries.

In terms of distance traveled - around 70% of work trips were shorter than five kilometers while about 10% extend beyond ten kilometers. No wonder many companies were coming up with models with a speed range of around 50-60 kph.

But the two-wheeler EV market would just not be limited to low-speed vehicles.

Vehicles with a speed of around 100 kph with a higher distance range. This segment user uses a two-wheeler for daily office commute and long-distance travel.

But EV manufacturing companies faced price affordability issues in this segment because the faster speed with a longer distance two-wheeler option is available in the combustion engine space.

But range and speed were not the real issues for the buyer looking at an ICE

Buyers generally compared the time between refuelling and charging. Refueling took 5 minutes, but full charging took >2hrs for EV two-wheelers.

The only solution was to swap the battery.

Ather initially started as a battery company for this very reason. Swapping was popular among two and three-wheelers because it requires small and lightweight battery packs. However, for four-wheelers, charging stations would still be needed.

The swapping solution allowed users to try out the EV models and took away the concerns around charging infrastructure.

But it would only be a band-aid solution for the longer-term infrastructure problem. This is purely from an economics perspective.

Assume a battery which was with a capacity of 3 kWh and cost Rs. 30,000. The one-time residential charge will cost the owner around Rs. 30 while the one-time swapping will cost Rs. 50-60. This is because the swapping company has to take care of infrastructure plus overhead costs.

Battery swapping works on the pay-per-use or subscription models. However, was expensive for the user in the longer term. Higher the usage, costlier swapping becomes for the owner and user.

By 2016, the Indian government had started to realize this was a problem that needed policy intervention.

Charging to Scale

India's charging infrastructure was relatively underdeveloped versus the rest of the world.

The changemaker would become the FAME Policy, or the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles.

FAME was designed as a part of the "Make in India" initiative to provide subsidies to the manufacturers and end-users so that EVs can be provided at a reduced price.

In mid-2016, GoI drafted FAME I, which aimed to promote vehicle manufacturing. In the 1st phase of the scheme, about 2.78 lakh EVs were supported with a total demand incentive of Rs. 343 Crore.

But by 2017, policymakers realized that providing the incentive will not push the EV adoption beyond a point. Range anxiety was the real problem.

It was necessary to address the core of the problem, which was charging infrastructure for the vehicles..

By 2018, the problem was identified, and subsequently, a tweak was needed.

Under FAME II, the Govt. now aims to create and push a charging infrastructure.

The FAME II plan involves paying subsidies to all two-wheeler purchases (commercial and personal). This was expected to lead to an increase in two-wheeler sales which would further reduce prices.

Under FAME II the Government agreed to support 1 million electric two-wheelers (among other vehicles) with an incentive of INR 20k per vehicle with the ex-factory price has to be less than INR 150,000. These incentives will be provided to the OEMs only if there was 50% localization for two-wheelers, three-wheelers, and cars.

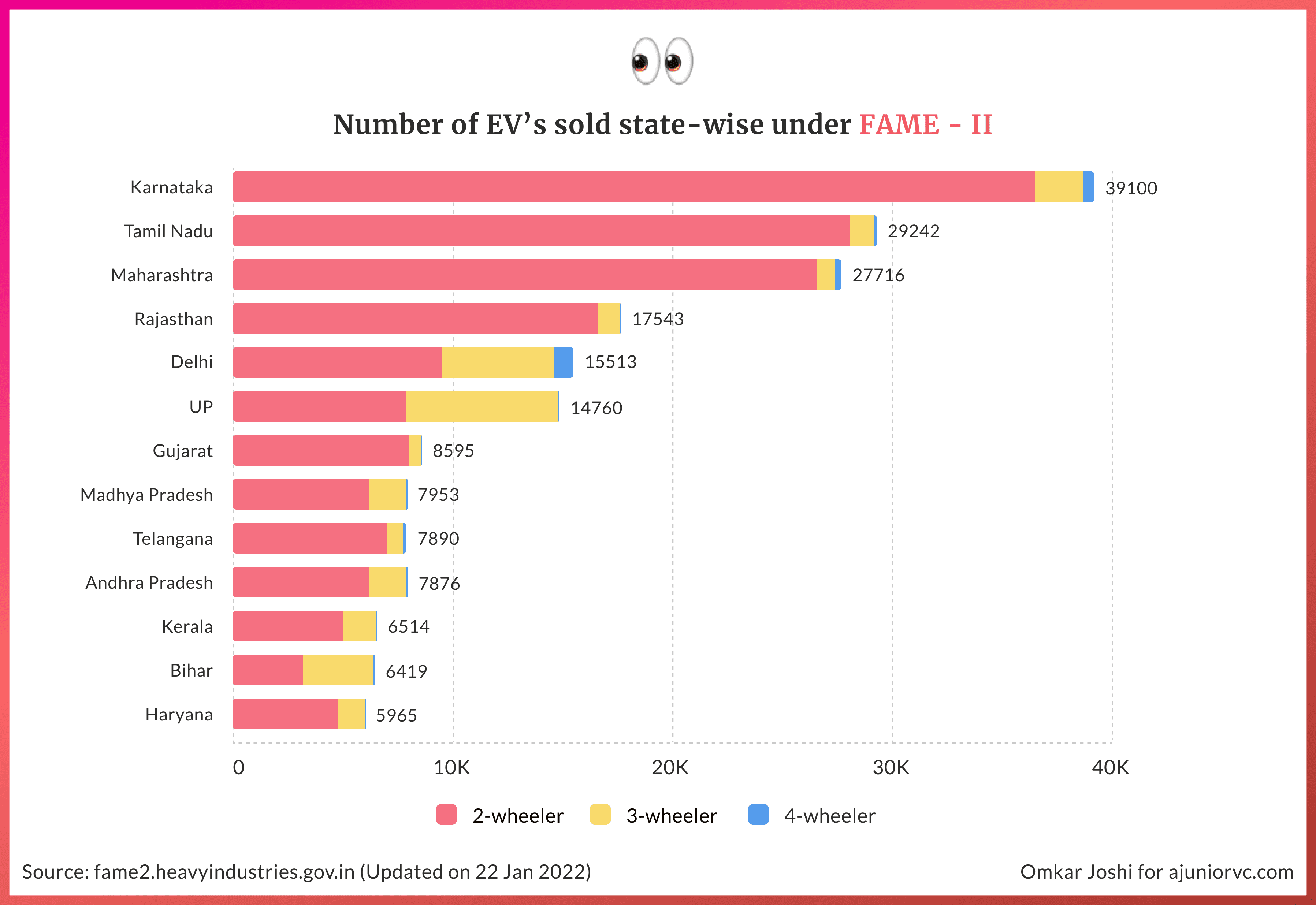

Individual states were also chipping in with EV policies and investments. For example states like Delhi set a target of having 50% electric buses in public transport by 2023

After that, a shift in infrastructure started to trickle in.

In late 2019, the Government approved 2,600 charging stations to be set up under FAME-II. The government kept working on the sidelines as players started to ramp up facilities

Apart from this, fleet began creating a network of their own. Fleet operators were investing in private charging networks. This would be a differentiator once the EV space is crowded with many vehicles

Creating a massive infrastructure was not going to be easy. But policymakers and EV players were determined to work together so that the adoption happens faster.

But if the government was providing the right policy framework for enabling, the sector got a massive marketing boost.

Ather’s Thunder Meets a Shadow

Ather launched its first scooter in early 2020, later than planned, but a very good one.

Its rollout was slow and started delivering in late 2020. Nevertheless, having worked hard and building an entire vehicle from scratch, it was the hottest kid on the block.

As it completed 2020, it had sold ~3,000 vehicles. Growing 30% of the year, that would imply ~30Cr of sales.

A good start from the young upstart would have helped it enter 2021 on a strong footing.

Yet, other machinations were rumbling, from a corner that Ather was not expecting. Cab aggregator Ola, which had setup Ola Electric to run e-taxis, acquired an electric scooter firm. In a widely publicized post, Ola said it was setting up a 2 wheeler plant in Tamil Nadu.

Suddenly, the category had a huge marketing blitz.

Ola would open a sign up form for its vehicles in July. The two-wheeler from Ola Electric saw significant promotion. In the first couple of days of pre-bookings, it got 1 lakh orders.

Who’d have guessed.

With its founder creating an ad shot in various locations, Ola was blitzing the market.

In the first two days of sales, it sold over INR 1,100 crore of scooters. However, just like the more illustrious Tesla Inc, Ola electric also ran into delays with executing its orders. It has been trying to make up for it’s execution deficiencies by marketing campaigns, teasers and videos about its large plant.

Not to be outflanked, Ather launched its own quirky ads.

The two were at loggerheads, providing a much-needed marketing boost to the market. The government too jumped on the bandwagon, advocating for an electric future.

This clear guidance and intent from the Government make investments in electric vehicles a no-brainer for the domestic auto majors.

However, the pace of the investments and rollouts would end up being different for different majors.

High Watt Competition or Scooting Away?

Not everyone was as excited as Ather and Ola about electric vehicles.

The country’s largest automaker Maruti Suzuki had no plans for entering the market before 2025. Among the reasons cited for the delay in investments were lack of government support, unavailability of charging infrastructure, and a desire to enter the market only if there was sufficient demand.

Spoken like a true big guy.

On the other hand, other automakers like Tata Motors had already launched the EV versions of their latest models. The success of Nexon EV, no doubt powered by the success of Nexon vehicle, had surprised many observers. The success was all the more sweeter because it was achieved during the Covid pandemic which took away almost the entire market segment of fleet services.

Tata achieved bookings of 3000-3500 units per month with only two electric cars. Seeing this success Tata has proposed to double down on its electric vehicle investments totaling up to $2 billion (15,000 crore) investments in the next 4 years.

As of now, in the four-wheeler segment most of the EV models were offered by European auto majors such as Jaguar, BMW, Porsche, and Audi.

Further investments by carmakers such as Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen were expected, considering the current level of incentives offered by the Government and the potential to export such cars from India.

Regarding electric bikes, the number of options was significantly higher.

The preference for electric scooters can also be seen in the number of models available which are currently at greater than 100. In the future, we are likely to see more and more automakers enter the market with their EV products. Incumbents such as Tata Motor, M&M, Bajaj, Hero have already prepared their product strategy for the market.

Bajaj went as far as saying that the new guys' OATS (Ola, Ather, Tork and SmartE) would be eaten by BET (Bajaj, Enfield and TVS) for Breakfast.

As 2021 began to come to an end, electric vehicle’s messiah Tesla ended up crossing $1Tn of market cap.

Breaking the Future’s Resistance

Tesla was worth all automakers combined, defying financial logic.

The heated valuations started percolating everywhere. Rivian, which had sold almost nothing, was worth $150Bn. Ola Electric, which still hadn’t shipped an actual scooter, was worth $5Bn.

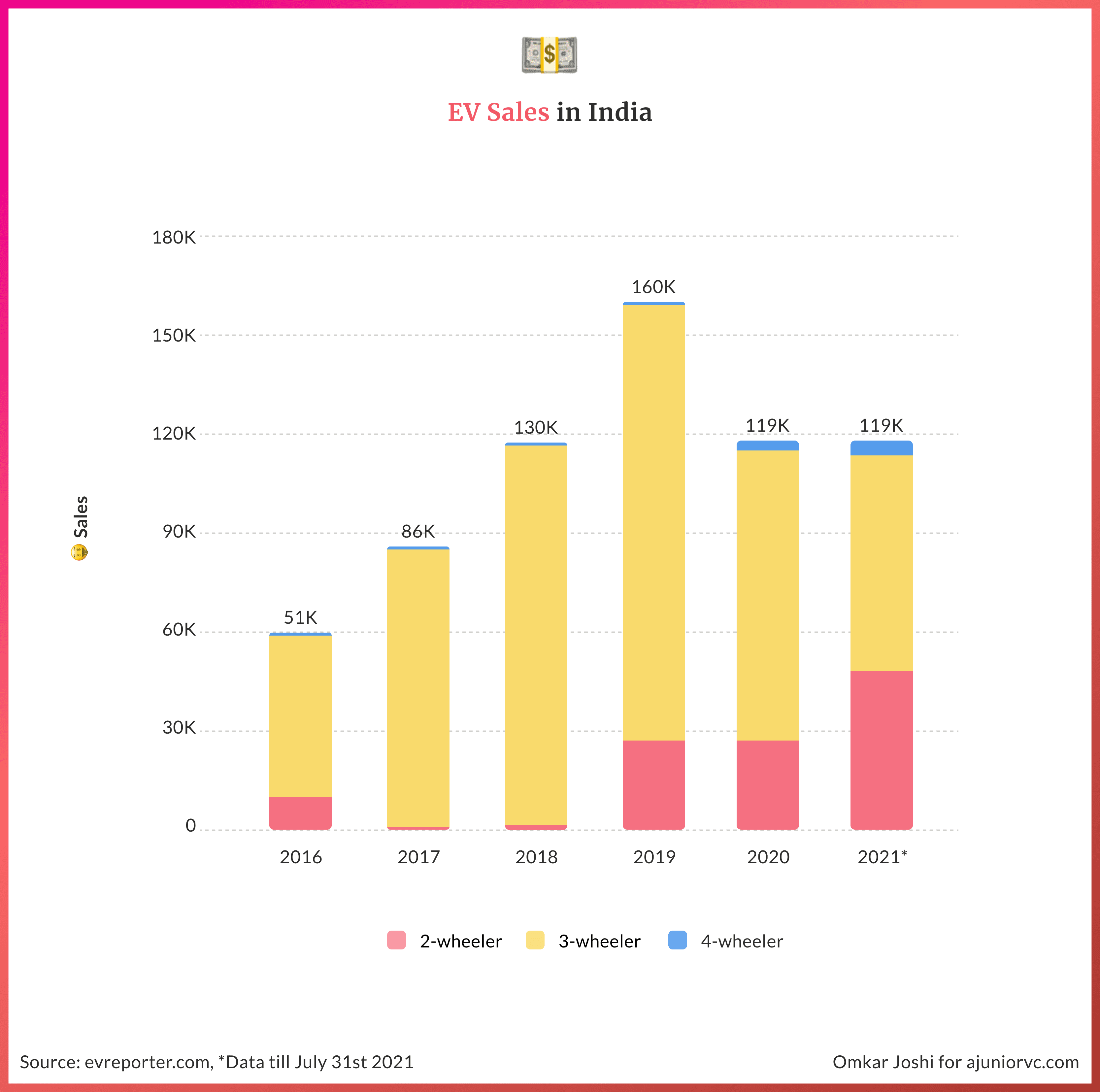

But the total vehicles sold in the entire Indian universe till data was barely crossing 100K, while vehicle sales were in multiples of millions.

The laws of physics, and business, have to eventually work to make these valuations real.

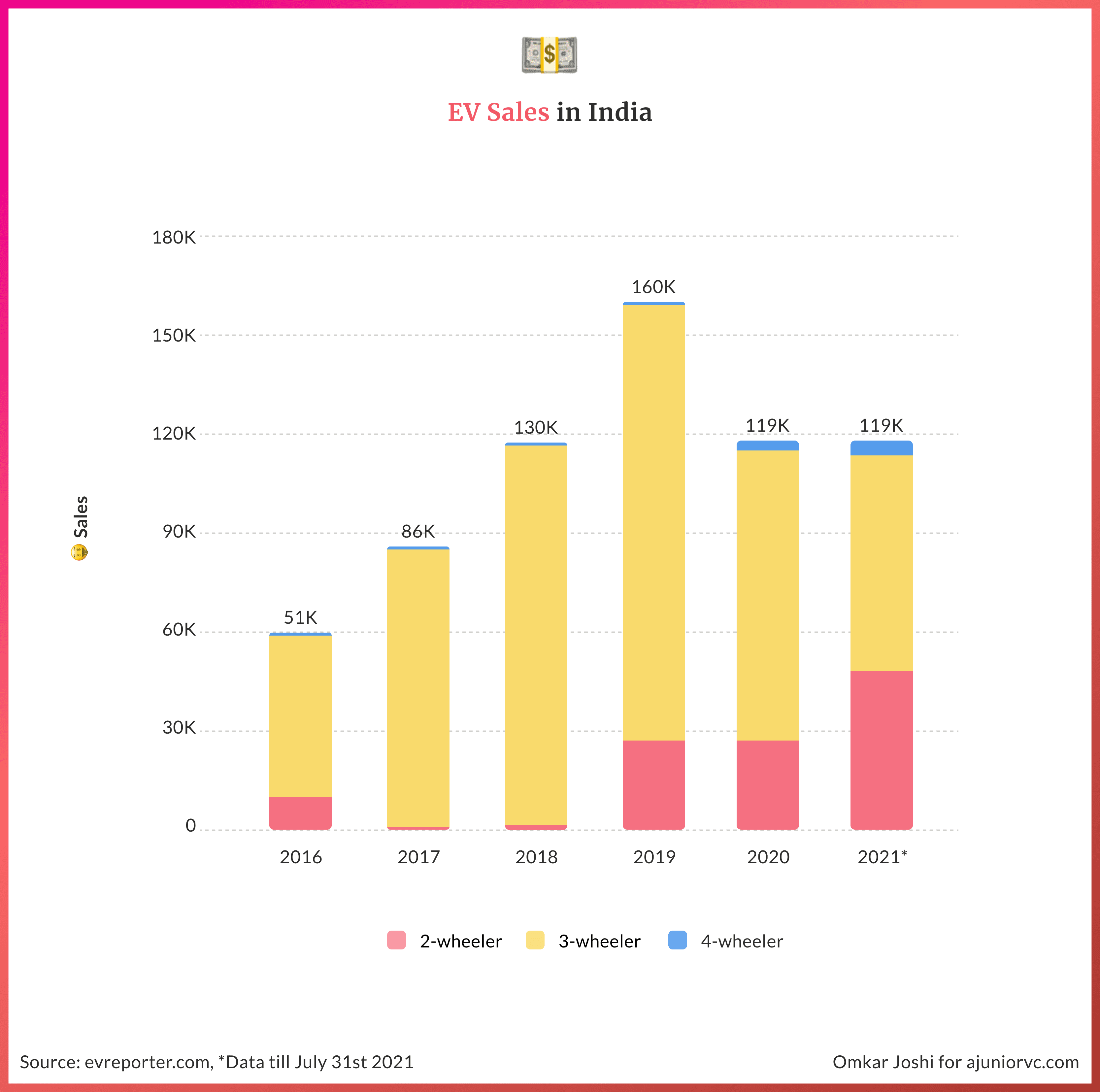

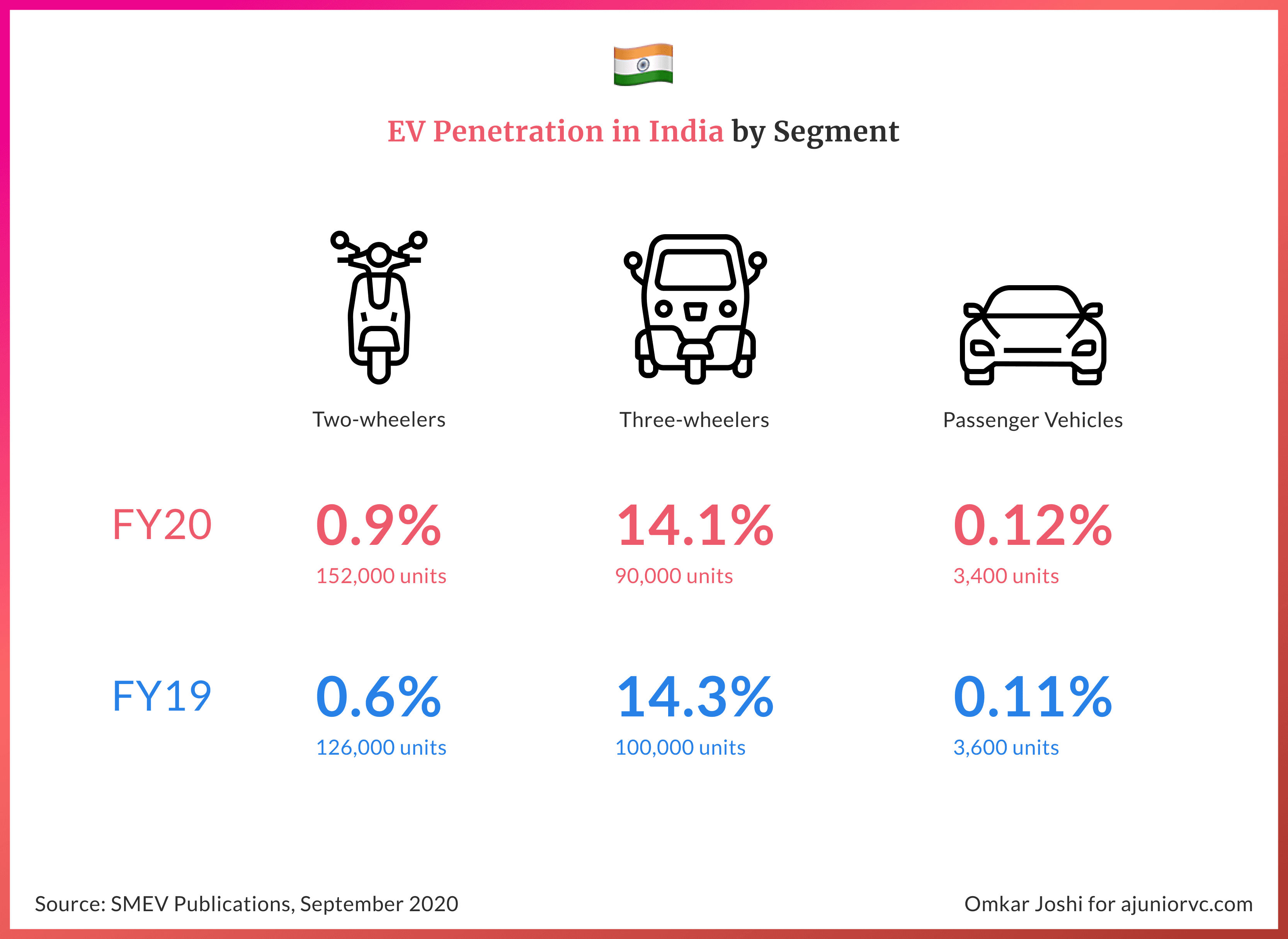

EVs currently account for less than 1% of total vehicle sales in India. Two-wheelers account for the largest share of this market at 62%, followed by three-wheelers at 37%. Four-wheelers are just about 1% in India.

The general opinion around the slower adoption of EVs is because of poor infrastructure. While that's true, however, it is not the only reason.

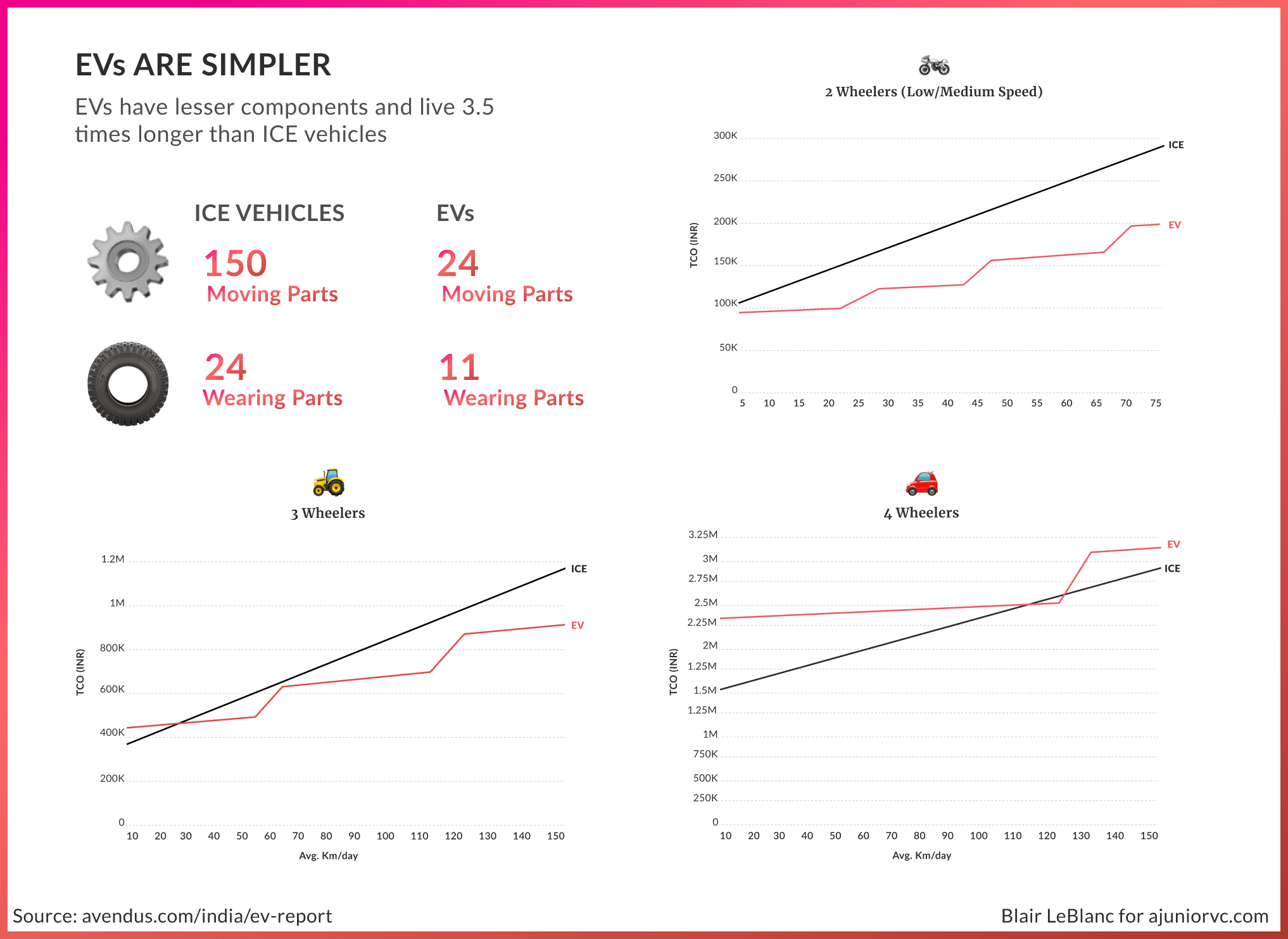

Economics plays an important role. That is measured through a concept called TCO (Total cost of ownership).

The battery is the most critical component. The battery of an EV constitutes up to 45-50% of a vehicle's cost, and battery costs have come down by 70-80% in the past decade. Despite this, the upfront cost for EVs is still higher than ICE vehicles.

But beyond the fixed cost, there is the operating cost

Compare the running cost - for ICE vehicles; generally, most low to mid-level segment vehicles (top speed around 80 kmph) provides an average of 50 km. That means Rs. 2 per km is the cost borne by the owners.

For EVs - generally, most low to mid-level segment vehicles (top speed around 70 kmph) provide an average of 50 km per charge (battery capacity 5 kWh). It costs Rs. 25 to charge the battery. That means Rs. 0.5 per km is the cost borne by the owners.

The per km savings of Rs. 1.5 is very significant.

Even if the upfront cost difference between EV and ICE Vehicle is Rs. 50,000, it will take around 30,000 kms to cover this cost. And if the owner is using the vehicle daily for just 20 km, then it will take 4.5 years to break even the upfront cost differential.

If we add maintenance differential, the break-even years will come down to 3 years.

The overall TCO helps us understand where the opportunities are. TCO is achieved much faster in 2-W and 3-W Vehicles, which have lower prices.

No wonder three-wheelers as a market for electric vehicles started doing extremely well. Even so, it is still a minuscule part of the overall vehicle market.

The number of 4 wheelers in India is ~30M, the number of 2 wheelers is ~100M. India sells 3M cars and 15M wheelers annually. From 1% today, the government intends to make 30% of 4 wheelers and 80% of two-wheelers sold electric.

Assuming a 2x market expansion, that is 2M cars and 24M 2 wheelers being sold, that are electric. With a 7 lakh average car price ($10K) and a 70K average 2W price ($1K), that is a $50Bn market being created.

This is the bull case, which makes the category attractive.

The challenge really is actually selling this number of vehicles. The government can’t “wish” for these numbers to happen. India is a cost-sensitive country with limited infrastructure. Without enough price incentives and supply build out the electric vehicle dream will remain just a dream.

The key bottlenecks are bringing down prices and improving access to infrastructure. If that is solved, it seems likely that people will switch to electric vehicles due to the cost structures. But a lot has to go right, very soon.

There is no doubt that people will switch to electric vehicles, but the question is how many and how soon. Market valuations always assume a time frame, and if we take 20 years instead of 10 years, the valuation should effectively be much lesser than half.

Electric vehicles hold a promising future but will be a premature fad if supply bottlenecks aren’t solved.

Writing: Chetan, Nilesh, Parth, Keshav and Aviral Design: Omkar, Mehak