Jan 26, 2020

Who Will Win FoodTech's Endgame?

Cloud Kitchen

Food

Brand

Aggregator

B2C

Platform

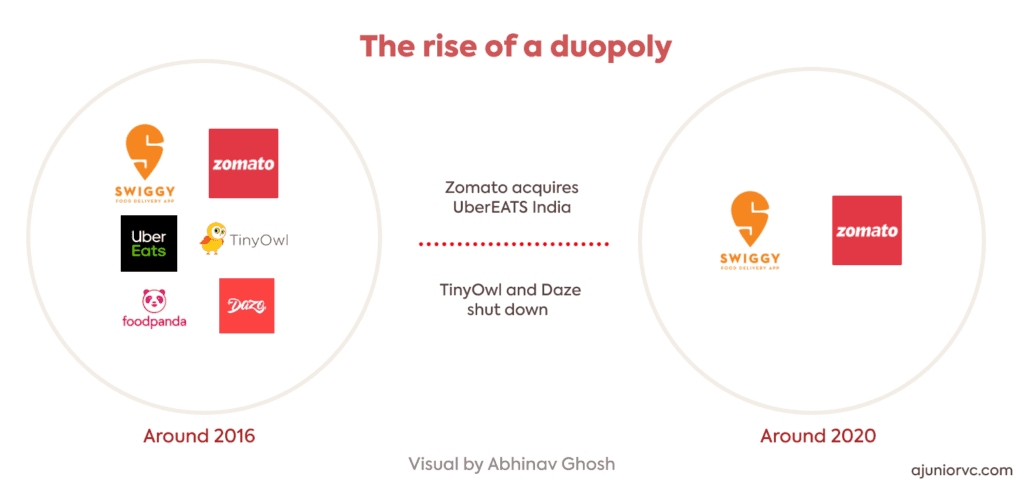

Last week, Zomato acquired UberEats for an equity valuation of $350MM, giving Uber 10% of Zomato in return and driving a consolidation in foodtech.

Deadpool

History may not repeat itself, but it certainly rhymes.

It thus certainly makes sense to study the history of India’s fledgling foodtech ecosystem. The foundations of the present state of food tech were set in the go-go days of 2015, when the number of startups funded exploded.

2015 is still the most well-funded seed/Series A year in Indian startup history, with $1.4Bn deployed in 540 investments.

2015 was also the year of hyperlocal investments. TinyOwl was the poster boy of India’s new food-tech ecosystem, raising $25MM over the year. At the time, there was a tiny company called Swiggy that raised a seed round of $2MM. Another giant company called Zomato was a unicorn.

PepperTap raised $50MM. RoadRunner raised $30MM. Hyperlocal investments in 2015 were at $430MM, 43x up from $10MM in 2014 and 30% of all investments that year.

The ecosystem was bullish on the potential of disrupting food delivery. Imagine the ability to deliver anything to your doorstep, in less than 30 mins with a push of a button.

Unfortunately, the optimism was not grounded in economic reality.

Only two companies in the previous paragraph live today. The deadpool of hyperlocal startups was either used for acquisitions by large players, or simply laid to rest. The reason for pulling the plug was that hyperlocal delivery did not make sense at the ticket sizes, where the cost of delivery was itself equal to the order value.

As we had observed earlier, most food-tech startups, ironically, died because of indigestion.

All the startups that raised an immense amount of capital expanded too quickly. In their quest to win the market, they tried to unsustainably acquire customers and suppliers. In their quest to eat, they ate too much.

Swiggy, on the other hand, did it slowly and sustainably. Starting with only Bengaluru, it took a year before expanding to other cities. Perhaps tempered by the foodtech disasters, Swiggy focused on not eating too much too quickly.

A lesson you must keep from here is, history certainly rhymes, as you will see later.

Enter FoodTech’s Captain Marvel

Less than five years ago, the way Indians consumed food was completely different.

Eating out was predominantly occasion-driven while ordering food was limited to calling local restaurants or ordering a pizza from Pizza Hut through their own websites.

Does anyone remember Meals on Wheels?

Online food ordering through apps was not a part of consumers’ culinary vocabulary. However, this has been transforming over the past few years.

Today, Indian consumers, especially in metro and larger cities, are ordering food online more often than before. As a result of this, food tech has become one of the fastest-growing internet sectors in India with an astonishing triple-digit growth rate in gross merchandize value (GMV) in 2017 and 2018.

After an initial hype among entrepreneurs and investors in 2015, the food tech industry saw a slump and market consolidation in 2016 and 2017.

Yet in 2018, India’s food-tech industry rekindled investors’ appetite for the sector with huge spending spree. Driven primarily by rising disposable income, rapidly growing internet and smart-phone penetration, urbanization, and a young and working-class consumer base, India’s food-tech industry drove up.

The foodtech market, comprising of tech-enabled delivery, grew from $300MM of GMV in 2016 to more than $4Bn in 2020, more than 100% each year.

The market may still be a drop in the ocean compared to international markets such as China with 10x the size at $40Bn+. The gap could be an indicator of unfulfilled appetite in the market and the subsequent investor interest.

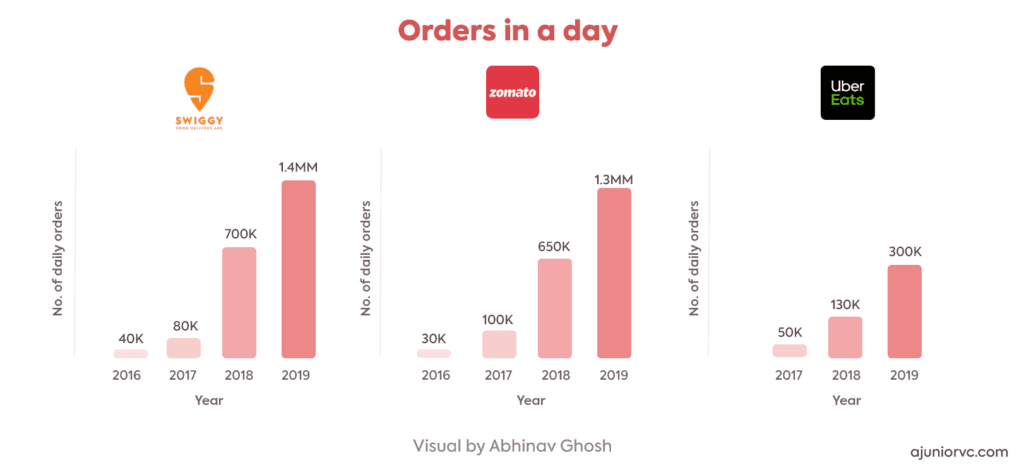

An average customer places an order at least 3-4 times a month with the frequency of ordering expanding to breakfast and snacks beyond lunch and dinner. Non-metro cities grew 7x faster as compared to metro cities in the last year. Daily order volumes grew 4x from 370K in 2017 to 3MM+ in 2019.

FoodTech’s Captain Marvel of growth was Swiggy, of course.

As the pioneer of scalably delivering food on time to your doorstep, Swiggy was followed by Zomato. Zomato, although worth $1Bn to Swiggy’s $10MM in 2016, was smaller than Swiggy.

Seeing Swiggy’s rapid scale, and Zomato follow, cab aggregators turned their wheels.

Failing Delivery Men in Black

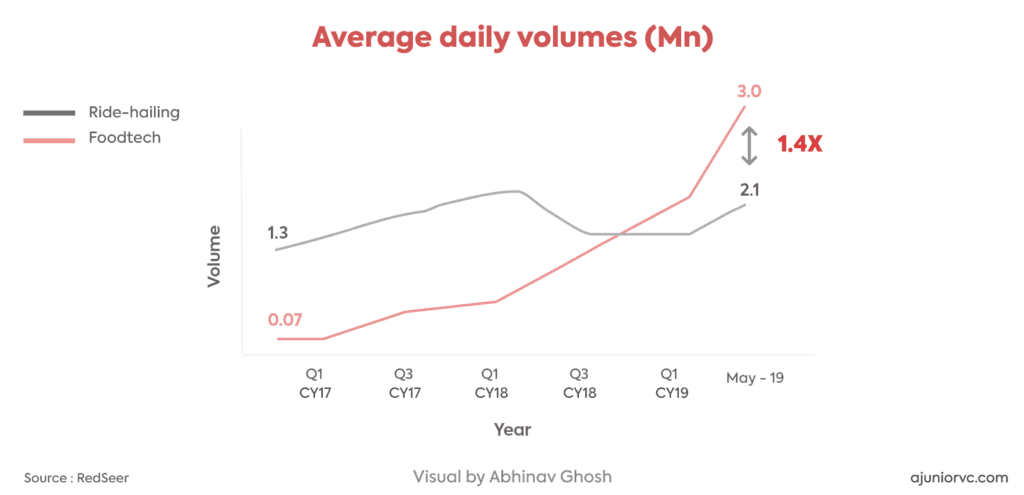

India’s cab-hailing aggregators’ entry in 2017 was strategic.

Ola acquired Foodpanda in Dec 2017 with plans to invest a further $200MM while Uber launched ‘UberEats’ in May 2017. It may seem like a random bet to monetize users, but the rapid scale of foodtech’s daily transactions compelled the ride-hailing companies to add another rapidly growing daily transaction feature.

If we see the entry of Uber and Ola in late 2017, you can see that food tech was beginning to show signs of an increase in pace.

While daily volumes in ride hailing was 18.5x those of foodtech in Mar’17 the gap narrowed and reversed over the past two years with foodtech becoming 1.4x of ride-hailing in daily volumes.

Uber and Ola may have seen the rapid rise of foodtech coming. In spite of this foresight, the ride hailers turned food techies have seen the going tough.

UberEats entered the market when the two incumbents had already gained significant mind share and was disadvantaged from being a late entrant. Unless it had a radically different strategy from the existing players competing in the tightly fought market did not make much sense.

Lack of differentiation in communication and branding strategy did not help further. It appointed one of the best actresses in Bollywood and tried to woo the millennials but the incumbents were still ahead with quirky campaigns.

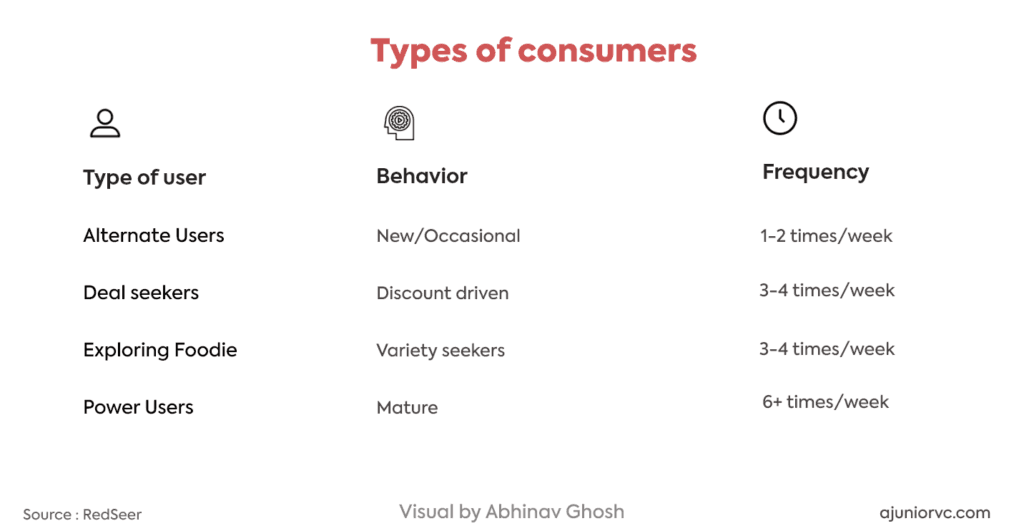

Price sensitivity and order frequency coupled with the size of the consumer segment determines the pricing strategy of the food-tech players. Newer players typically target the price-sensitive cohort, which are alternate users and deal hunters. This is due to their weak brand loyalty and lure them through promotions and discounts to gain market share.

Discounts of 20-50% are prevalent in the market and it becomes a real challenge for the food tech startups to then differentiate or create a strong loyal base.

Uber Eats targeted the first two cohorts deploying a deep discounting strategy. This led to rapid growth in user base which would switch to other apps if they did not find the best/ deals discounts on Uber Eats.

Uber’s lackluster IPO resulted in the parent entity realizing that it was a significant drag on margins which Uber Eats India business had. In a recent investor call Uber’s CFO had exasperated that without UE India, the adjusted net revenue would have been 11.1% instead of 10.7%.

Uber had to clearly let go of this business and let go fast. But what was the reason for letting go of what could be a lucrative business in a massively growing market?

Unit economics and indigestion, or history rhyming with itself.

The Eternal Problem of Unit Economics

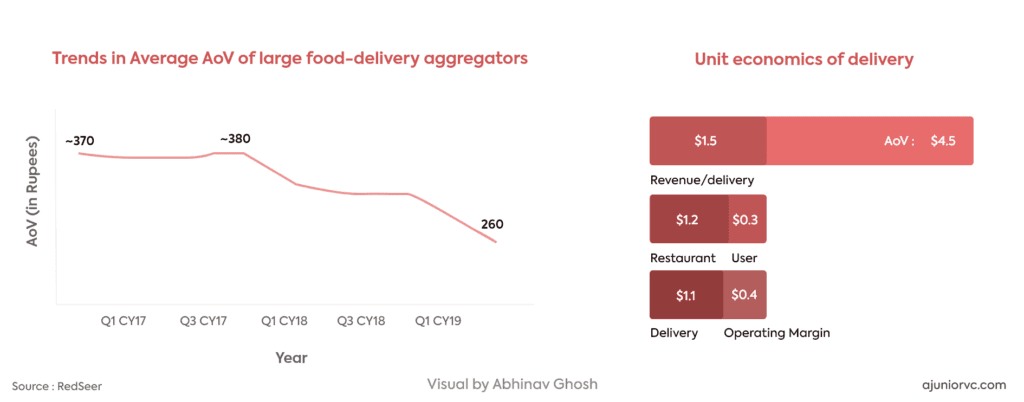

The problem of low average order value and repeat remains the biggest challenge in India.

India is at 1/10th of developed markets. A typical order in the US is for $20-$30 (INR 1,400-2,100), it is possible to make a positive contribution margin on an order. While developed markets see 40-50 meals ordered per month, Indians order food less than five times a month.

Expansion to tier 2,3 markets is also challenging with the risk of order value depressing further while the cost structure for delivery remains the same.

Further introduction of food delivery for single users such as Swiggy Pop and its success means that AoV is being further driven down, protracting the challenges for these players.

By 2019, the food tech companies would only see some light in their unit economics.

On an order of $4.5, a food tech company would on average make just $0.4, or 7% of the average order value. For the 400MM+ orders every year that Swiggy was doing, it was left with just $160MM (0.4*400) for financing its internal operations.

UberEats, with 1/4th the orders, was burning $9MM every month, or $100MM a year when it was generating just $20MM post-delivery.

The cost structure makes it clear that streamlining logistics to reduce delivery cost is the key to improve unit economics than a greater focus on convenience or restaurant delivery for the users.

Volume has been driven through an ‘addictive hook’ of discounts and cashbacks which needs to be curtailed and users need to be rationalized.

Zomato has been trying to streamline logistics and reduce burn. Zomato’s CEO remarked in 2019 that per order it loses INR 25 now compared to INR 44 in Mar 18. Its last-mile cost per delivery has also gradually reduced from INR 86 to INR 65 now.

The economics are being reflected now as it cut its cash burn to $20MM per month in Oct 19 compared to $45MM per month in Mar 19.

Even after this rationalization, the food delivery companies would need to look to the clouds to improve their margin.

Thor’s Economical Cloud Kitchens

Cloud kitchens appear to be the next big land grab for better economics.

Cloud kitchens allow delivery companies to make more margin than just aggregating. Similar to Amazon doing a white label of products, the food delivery players are white labelling food.

Foodtech players hope this is the hammer to break the unsustainable economics.

Like in delivery, where Swiggy moved first, the Swiggy Access program appears to be working best. Its big bet on cloud kitchen has played out well. One in three partners has expanded to a second kitchen within 90 days of signing up while smaller city restaurants have broken into bigger cities.

As of Nov 2019, it had established 1K cloud kitchens for its restaurant partners, more than any of its rivals. In the long run, Swiggy targets to have 20-25% of its orders from these delivery-only Access kitchens.

An erstwhile food delivery startup, Faasos, is now a full-fledged cloud kitchen player. As we had elaborated in our piece earlier, cloud kitchens would be the brands to the retailers that Swiggy/Zomato were.

The scalability of cloud kitchens coupled with attractive margins could help improve the economics of food delivery players.

The biggest cost head of rental is eliminated, which enables kitchen operators to spend more on sourcing quality ingredients or reduce pricing to make it an extremely attractive value proposition for customers. Additionally, being a space just limited to cooking, multiple cuisines can be cooked in adjacent areas to drive utilization of space up.

Another trend is that subscription users of cloud kitchen apps exhibit strong platform loyalty vis-à-vis, on-demand users, even if the dish they are looking to purchase is unavailable. This is very similar to preferences for brands while shopping on online retailers.

But as the food tech players look for better economics, what will happen to the market?

Entering The Dark World of Profitability

As investors start to value profitability and sustainability over growth at all costs, we expect a correction in the unbridled adoption of foodtech and delivery services.

As with ridesharing, prices will start to rationalize as companies realize that there needs to be a path to profitability for them to succeed in the long run.

Over time, new fees and revenue streams will come into being like Swiggy Super, which charges a monthly fee in lieu of delivery fees and surge prices.

Players in the industry that hope to win consumers and turn a profit will need to segment their customers in a way that allows them to increase order values, maximize retention, and build recurring revenue streams that don’t vary in response to discounts and promotions.

Consolidation, like Uber Eats’ eventual exit from the Indian market through an equity partnership with Zomato, will increase and eventually the Indian food delivery wars will reach a steady-state where the logistical network built by the industry leaders allow for profitable deliveries, economies of scale, and ultimately higher levels of customer satisfaction.

The consumers who have got used to the lower prices and convenience seen in food delivery but simply can not afford the service once price rationalization kicks in will revert to cooking at home and saving outings for special occasions.

The much-awaited expansion of the Swiggy’s and Zomato’s of the country into more tier 2/3 cities will come later than expected, if at all. The conversation around this expansion could change with increasing infrastructure being built in those cities, but that would be a 5-10 year at the least.

Zomato’s acquisition of UberEats in this backdrop starts to make a lot of sense.

Facing Off in an Infinity War of Capital

As we talked about earlier in the piece, Uber Eats’ exit from the country through a sale to Zomato is food tech's biggest news to date.

In what some consider a master chess move from Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber was able to hive off a business unit that contributed just 3% of gross bookings for the business globally in the first nine months of last year, while accounting for a quarter of its adjusted operating losses.

The financials do not tell a pretty story.

Uber Eats India was burning through funding in the competitive Indian market, making a loss of $61MM on revenue of $20MM in the 3rd quarter of 2019.

The sale will allow Uber to cut its losses and yet keep a 10% stake in what could be the winner of a market expected to be worth $15 billion by 2023.

For Zomato, their orders per month will rise by 10 million from 38 million it was clocking, putting it above Swiggy which receives around 40 million in monthly orders.

The acquisition does not guarantee that all Uber Eats customers will switch to Zomato because the market is still crowded with customers that tend to favor companies offering the best deals.

Many view this as a strategic move by Uber in India to refocus its energy and focus on markets where it is most likely to succeed as the biggest or second-biggest player. In this case, its core ride-hailing business where it is locked in fierce competition with Ola.

Uber’s decision is reminiscent of similar strategies employed by it in the ride-hailing space. In markets where it is has felt unable to fast-track its quest for profitability, Uber has merged its business with local rivals: Yandex in Russia, Didi in China and Grab in Southeast Asia.

Ironically, Uber’s main rival in India’s ride-hailing market – Ola – also burnt its fingers (twice) in the food delivery market, first with Ola Café and then by buying FoodPanda in late 2017 only to exit in mid-2019.

In the meantime, Uber Eats’ exit means that the Indian food delivery market has now effectively become a duopoly, with a straight fight on the menu between the two unicorns: Zomato and Swiggy.

Even outside of the Uber Eats acquisition, there are some interesting differences between the business models that Zomato and Swiggy have pursued in their quest for growth and domination of the sprawling Indian market.

Swiggy diversified its business operations by expanding its cloud kitchen network, forayed into home-cooked / packaged food deliveries and parcel deliveries.

Zomato tried its hand at becoming a ‘full-stack player’, covering the gamut from sourcing, storing and supplying raw materials to its partner restaurants and its own cloud kitchens.

But what is probably more interesting, is the geographical difference in popularity between the two.

Through the Zomato-Uber Eats deal, Zomato gains access to Uber Eats’ extensive network of delivery partners, without fretting too much about cash burn. There is the added prospect of bolstering its presence in some cities, especially in South India, where Swiggy has the edge.

Both Swiggy and Zomato have a presence in 550 cities, but their markets are different.

Zomato is strong in the north, which accounts for almost 70 percent of the 36 million orders it gets in a month, company sources said. It is the other way round for Swiggy, with the south contributing to about 70 percent of the 42-45 million orders it services in a month.

Sixty-five percent of UberEats’ 10 MM orders came from the south. Put UberEats and Zomato together and the count for southern India can go up to about 14-15 million orders a month.

UberEats had 30 percent of the market share in the south, second only to Swiggy, which dominated the market with a 55-60 percent share. Zomato was a distant third.

Lunch and dinner counted for the bulk of Zomato orders but UberEats was strong in the breakfast and snacks segments, according to Zomato executives. And, South India loves its breakfast, especially when it is ordered online.

With the additional firepower of Uber Eats’ operations, access to the who’s who of the investing world that resides on Uber’s cap table, and influence from a global brand with a presence in every market one can think of, the path to Zomato winning India’s food delivery wars is shaping up nicely.

Being full-stack in a market where home deliveries are likely to get rationalized while eating out remains popular, will only help Zomato.

But while the new duopoly suddenly finds themselves as the two standing after a bloodbath, a dark cloud is hovering.

The Thanos of FoodTech’s Endgame is Amazon

Amazon could make food delivery another feature of its vast array of services.

You may wonder why this makes any sense, especially in the backdrop of two ride- hailing giants trying to add “food delivery as a feature” and failing. Indeed, the worry of a large giant coming and disrupting an upstart is usually misplaced because of the deep market understanding needed to scale.

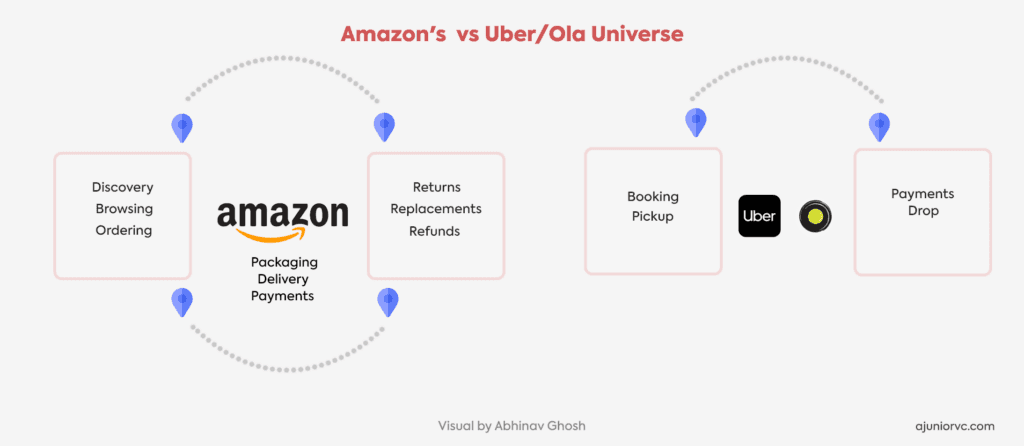

But that is before you see how close Amazon is to Swiggy/Zomato, and how far Ola and Uber were.

At a superficial level, Ola/Uber (O/U) had mastered the art of moving 4 wheelers while Swiggy/Zomato (S/Z) primarily run a two-wheeler movement business. Digging deeper, you realize that O/U only care about what happens during transit. You don’t really care too much about which car you’re getting as long as it's there quickly, and U/O don’t really care about what you do after you get off the car.

S/Z on the other hand, need to solve for the “before and after” really well.

The foodtech players need to provide you with a well curated range of food brands to browse through and discover. You mention to them your food requirements and specifications, and they should care about how the food is experienced. The food needs to be packaged well and delivered on time. If the food is bad, or a specification you gave was missed, you’re likely to be immensely frustrated at S/Z.

Most importantly, S/Z deliver food from one fixed location (food brand) to another fixed location (home)

Replace S/Z with Amazon and food with product, and you can see why Amazon could snap its fingers and turn on food delivery as a feature.

As you recollect, most of the margin in every order is spent on delivery. The company that simply has the most efficient delivery infrastructure in the country today is Amazon. Personally, Amazon has more touch points per week than any other internet company.

With $40Bn of e-commerce sales, and assuming a high order value of $10, 4Bn orders are delivered every year, or 15MM orders everyday. Assuming Amazon has 50% of these, Amazon is delivering 8MM orders everyday, of incredible complexity to more pincodes than S/Z. Its $20Bn GMV is 5x of food tech’s entire GMV

You may think that S/Z have the moats of restaurant data, but that is hardly a barrier.

While people may not know a seller on an e-commerce marketplace, hyperlocal knowledge is deep. Even without S/Z’s rating, you are fairly aware of the quality of a restaurant in your locality. The key bottleneck will therefore not be restaurant data, but getting the restaurant’s onboard.

It is no surprise that Amazon has already begun to lay the foundations of entering the market last month.

It is also completely unsurprising to see Amazon investing $575MM in Europe’s food delivery giant Deliveroo, and facing antitrust suits. What may give solace is that Amazon has not been able to crack hyperlocal as fast as some would have expected, with BigBasket still chugging along in groceries.

But it does not mean that the Endgame will not be won by Amazon, the end may just be prolonged.

In a few years, S/Z may not be a duopoly, but consolidating to fight a monopoly called Amazon. Whether this story plays out like Marvel’s Cinematic Universe or turns out to be a Thanos dominated alternate universe remains to be seen, but the consolidation is definitely not over.

The winner of foodtech’s endgame may not be Swiggy or Zomato, but Amazon.

Written by: Aviral, Keshav, Rohan, Shiraz