Jun 25, 2023

Has $20Bn Indian VC Reached its 20-Year Peak?

IPO

B2C

B2B

Venture Capital

Last fortnight, Sequoia India rebranded to Peak XV, as governance issues and lack of fundraising continued to send deep fear in the Indian startup ecosystem.

How Can We Be Helpful?

In 1950, a newly-liberated India was bustling with activity.

On the one hand, there were the trials of nation-building, with attempts to address poverty, illiteracy, and economic disparity. On the other hand, an era of scientific awakening was unravelling, courtesy of establishing the IITs in the 1950s.

The IITs were dreamt of as more than just centres for academic prowess. They were a testament to a nation ready to dream, innovate, and create.

As IIT Bombay was being founded in 1958, across the world, another revolution was brewing.

William Shockley, a Nobel laureate, and his eponymous company, Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, were tucked away in the sunny stretch of California. Shockley was a brilliant scientist, but his managerial style left much to be desired.

It was only a short time before eight of his brightest employees, unhappy under Shockley's reign, decided to branch out. These 'Traitorous Eight' initiated a technological exodus to shape the industry's future.

Arthur Rock, then a young securities analyst from New York, would help connect these to businessman Sherman Fairchild.

The eight founded Fairchild Semiconductor, a company that would pioneer the integrated circuit, the heart of every modern electronic device. While Fairchild was an innovative enterprise, it became a fertile ground that sprouted numerous 'Fairchildren' companies founded by ex-Fairchild employees.

The most famous would be Robert Noyce, who founded this little company called Intel. But one of the lesser-known Fairchildren, Eugene Kleiner, would give birth to an entire other industry.

As the Fairchildren got to work, Tatas were busy playing their part. Amidst the humming factories and towering chimneys, J.R.D. Tata, the group's then-chairman, saw a new avenue - the future was not just in producing goods but also in processing information.

The Chairman found a leader in Faqir Chand Kohli. It was a proposition to charter the unknown, to lead the Tata Group's foray into this new thing called computers.

In 1968, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) was born.

He was to build from scratch an IT company in a country where computers were a rarity. For him, it was more than just a job; it was a mission to transform India's tech landscape.

As TCS took baby steps, a new industry began taking shape. Not so young anymore, Arthur Rock would coin the term “venture capital”. He would also become the first VC in Intel, having known the Fairchildren for a decade.

The significance of this migration to the US Venture Capital (VC) scene was rooted in the inherently high-risk nature of these ventures.

Traditional bank loans didn't quite cut it for these fledgling tech companies. Startups were inherently risky. They often need more tangible assets, making them unsuitable for collateral-based bank loans.

A whole new form of financing, inspired by whaling expeditions of fees and carry, was getting formalised.

In 1972, Eugene Kleiner founded Kleiner Perkins Caufield and Byers. KPCB was born out of a clear vision - to financially back visionary entrepreneurs. But KPCB did more than write cheques; it became an industry architect.

KPCB would be the birth of the mecca of venture capital - Silicon Valley’s Sand Hill Road.

Another young marketing professional at Fairchild, Don Valentine, learnt the ropes of the burgeoning tech industry.

Valentine noted technology's transformational role in business and saw the untapped potential in backing emerging tech companies financially. With this insight, in 1972, he founded a VC firm inspired by an enduring Californian tree next to KPCB.

It would be called Sequoia Capital

Meanwhile, in India, taking success from TCS, Shiv Nadar laid the foundation of HCL Technologies, and Narendra Patni founded Patni Computer Systems.

India at that time didn’t have a startup ecosystem, let alone a VC firm. The 1980s saw the birth of Infosys, a startup story in the truest sense.

An urban legend is that Sudha Murthy, wife of co-founder N.R. Narayana Murthy, gave the company its first "venture capital". This period also witnessed the emergence of Wipro, NIIT, and many other tech companies, most of which congregated around the sleepy town of Bangalore.

As India’s technology scene took shape, established players like Sequoia shifted gears, and a new player entered the field.

In 1983, Accel came into being.

Accel represented a new paradigm. The firm started the trend of thesis-driven investing by identifying sectors they were interested in. As Accel took birth, Arthur Rock and Sequoia’s investment in this little company called Apple would be a monstrous success.

Venture capital in the US was no longer a cottage industry, soon colliding with dreamy-eyed Indian kids.

IITians on Speed Dial-Up

In the late 1980s a handful of computer science graduates from the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) made a beeline for the United States.

They were driven by curiosity, ambition, and US market size. Many of them were attracted by the growing importance of a mysterious little thing called the 'internet'.

Little did they know that they were sowing the seeds of a dramatic transformation back home.

American tech companies searched for sharp, hardworking minds to fuel their digital dreams. These fresh-faced IITians fit the bill perfectly.

It was the early years of the World Wide Web, and computer science was starting to flex its muscles. With their rigorous training and technical prowess, they were primed to ride the wave.

In 1996, the tech world was merely sprouting the USA, a far cry from the mammoth it is today.

Ashish Gupta, Anand Rajaraman, and Rakesh Mathur, all IIT graduates, met at Stanford University. Joined by Ram Sriram, who was previously at Netscape, they established Junglee, a search engine ahead of its time.

Their primary objective was to revolutionise how people navigated the burgeoning World Wide Web. At the time, online search was in its infancy and lacked the sophistication and capability to handle the rapidly growing web content.

Within 2 years of starting Junglee, Ram Sriram collaborated with two young Stanford kids, Larry Page and Sergey Brin to create another search engine—Google.

Junglee believed the web would be used primarily for shopping, while Google wanted to build it for knowledge search. The world may have been vastly different if Junglee had won.

In India by 1997, Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited (VSNL) launched India's first dial-up internet service, a seminal moment that catapulted the country into the digital era.

It was a strategic move towards digitisation aimed at harnessing the power of the internet for economic development.

1997 saw a flurry of tech startups sprout across India.

Companies like Naukri, JustDial, Zoho, and Shaadi were established, setting the tone for the IT services boom. Infosys, an Indian IT giant, experienced unprecedented growth, doubling its footprint and becoming the harbinger of the outsourcing revolution.

While VSNL had electrified the Indian internet, the US internet had gone wild.

The legendary hedge fund manager Julian Robertson managed over $22 billion in assets at his Tiger Management fund. In a case of deep future irony, he attempted to short technology stocks.

But with the internet bubble of 1999, he was left licking his wounds and he had to close his fund. 1999 was an adrenaline rush, with internet stocks creating a frenzy in the market.

IT stock in India made a fortune. Between 1999 and 2000, the share price of Infosys witnessed a massive 17x jump. Pumped by the “Y2K bug”, Infosys grew enormously fast.

The success of Infosys significantly impacted Bangalore. The company's expansion created thousands of jobs, attracting a wealth of engineers from across the country.The trifecta of capital, innovation, and first-time entrepreneurs was the secret sauce that gave birth to Bangalore.

It would become the epicentre of India’s startup movement.

Bears, Bubbles and Bengaluru

While India with engineers, the startup culture remained a far-off reality.

It was akin to having the perfect kitchen without the right recipe. However, as 2000 approached, things started changing.

The dawn of the new millennium saw MakeMyTrip's foundation and Naukri securing its first round of funding, followed by the market's dramatic collapse.

Indeed, Tiger’s Julian Robertson had the right idea but just the wrong timing, like showing up in a Halloween costume, in November. He looked at the tech bubble, saw the precarious wobble, and thought, "This won't end well!" And it didn't, eventually.

Just not before it cost him a pretty penny.

He would go on to seed a few of his employees, called Tiger Cubs. One of them would be called Tiger Global Management.

But before Tiger’s romp in India, there was ICICI Ventures

It was the sort of financial wizard that had been conjuring up funding miracles since 1988, long before 'venture capitalist' was a trendy job title in India.

In the rubble of the burst tech bubble, they backed businesses like PVR, essentially saying, "Popcorn, anyone?" while others worried about their bread and butter.

Doubling down on a business heavy on capital expenditure back then was a bold gamble by ICICI Ventures. It was like investing in a super-sized popcorn machine when everyone else was haggling over kernels.

The late 90s marked the phenomenal growth in India, with the economy expanding by almost 9% in many years. This impressive infrastructural development lured the Indians who had gone abroad to study in the 80s and 90s, back home.

Suvir Sujan and Avnish Bajaj, two Indian exports, recognised early the tremendous potential e-commerce held in the burgeoning Indian market.

In response, they established Bazee, an online auction and marketplace platform. Like eBay, Bazee was designed to empower individuals and businesses to trade seamlessly within a trusted online environment.

Bazee emerged as a trailblazer in the Indian market, raising $19M (Rs.100 cr.) and providing a unique online platform for trading various goods. Incredibly, ICICI invested here too.

Its concept was reminiscent of the virtual evolution of a traditional Indian bazaar, always open and available right at your fingertips, connecting sellers and buyers nationwide.

The success of Bazee didn't go unnoticed.

In 2004, eBay, the global titan of online auctions, acquired Bazee for an eye-watering $50M. This move was a strategic chess game, allowing eBay to establish its footprint in India and gain access to a promising market showing signs of a digital boom.

This acquisition was a significant moment in India's e-commerce history. eBay's entry into the Indian market was not just a stamp of validation for the country's e-commerce potential but also set the stage for a deeper VC market in India. Bazee’s two founders would begin to think of life on the other side of the table.

This move set the stage for the e-commerce battle in India, with eBay establishing its fortress well ahead of its rival, Amazon.

With an exit in hand, the stage for India’s VC ecosystem was set.

Cambrian Explosion of Seeds

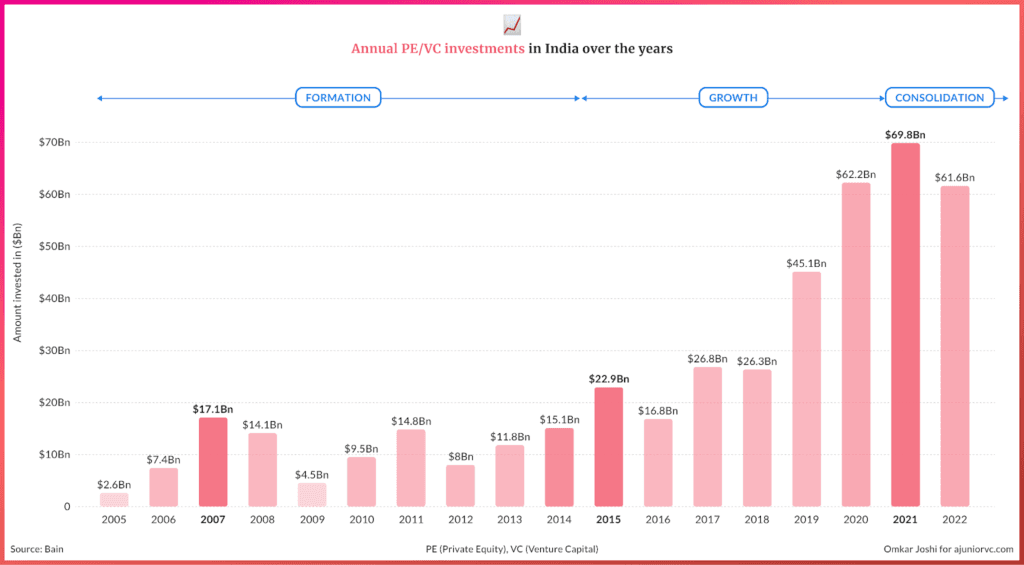

2006 would be the year India VC would explode, entering its first big peak.

The main characters of our story, who had migrated to the US, would flood back to India and set up venture funds in the same year. Nexus Venture Partners (NVP) was founded by Bazee’s co-founders Suvir Sujan, Sandeep Singhal and Naren Gupta. Avnish Bajaj founded Matrix Partners India office. Helion Ventures was founded by Junglee’s founders Ashish Gupta and Sanjeev Aggarwal. Erasmic Ventures was founded. IDG Ventures was founded. Indo US Venture Partners was founded.

Softbank Asia Infrastructure Fund, or SAIF Partners, scaled rapidly. Westbridge Capital, another fund set up by Indian returnees, became Sequoia Capital.

All incredibly, in 2006, almost like an arms race.

Other funds would soon follow. Bessemer Ventures Partners, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, Lightspeed Venture Partners.

The dominant force driving the growth of venture capital in the country as of this date was a belief that India could be the next China. If that was likely to be true, this was the time for VC funds, particularly those focusing on seed funding, to set up shop in the country.

Helion Ventures raised $140M and another $260M in two years. This was a significant event for a homegrown VC firm. The fundraise demonstrated early confidence of the world in the India story.

The business model of VC was straightforward.

VC firms raise money from large investors like college endowment funds, Limited Partners or LPs. LPs wanted access to the risky asset class of venture. The VC firms’ managers or General Partners (GPs) deployed this into startups. In exchange, they would get fees to manage the money, usually 2% and a share of profits called carry, usually 20%.

As VC funds proliferated, so did a new crop of angel investors

These angel funds were predominantly funded by Indians who had some exposure to the VC culture in Silicon Valley and wanted to give back to society.

The network also contained a group of prominent successful entrepreneurs in the country. The Mumbai Angels was founded in 2006 and were followed up with the setting up of the Indian Angel Network in April 2006. The Chennai Entrepreneurship Trust Fund would start in Nov 2007, later known as The Chennai Angels.

Angel investors provided constant access to high-quality mentoring, vast networks and inputs on strategy and execution. The network members could scout and give small checks to startups trying to begin.

The year was punctuated with several deals, which would soon be the stuff of folklore. SAIF Partners would double down on MakeMyTrip.

During 2005 to 2008, SAIF Partners invested about $25 million in MakeMyTrip between 2005 and 2008. It owned about 41% stake in the company when it debuted on Nasdaq in 2010. SAIF also invested 55 crores in Justdial, which could go on to do an Indian IPO.

Erasmic would be acquired by Accel, with Accel entering India in 2008.

The positive news about the Indian business ecosystem did not seem to end as the listed Indian IT firms then crossed a psychological valuation of 10 Bn dollars on the stock exchanges. This valuation increased the overall confidence of the ecosystem that good things were soon to happen.

In the form of a tiny bookstore, they were about to.

A Kart is Born

2007 and 2008 were years of promise

These two years saw the birth of landmark companies like Flipkart, InMobi, Myntra, Dream11.

Flipkart started its journey from Bangalore in 2007 with a personal investment of INR 4 lakh. They got their seed of $1 million from Accel India in 2008.

InMobi, then called mKhoj, started in 2006, and Myntra, founded by Mukesh Bansal, Ashutosh Lawania, and Vineet Saxena, began in 2007. Myntra secured seed funding in October 2007 from Accel Partners, Sasha Mirchandani, and others and their Series A of $5M in November 2008 from NEA-Indo-US Ventures, IDG Ventures, and Accel Partners.

For example, Intel Capital set up a $250 million India Technology Fund in 2005. In 2008, Intel announced an investment of $17 million into three Indian companies - travel portal Yatra.com, events-oriented social networking portal BuzzInTown.com, and out-of-home advertising firm Emnet Samsara Media Pvt. Ltd.

In Jan 2009, they invested $23M In One97, IndiaMART & Global Talent Track, a Training Firm. Despite being a corporate arm, Intel would become one of the most successful venture firms in India.

By 2009, the first echoes of smartphones had started to come in India following the iPhone launch. Early e-commerce in India happened mostly from desktop computers.

Every year, the share of e-commerce from mobile phones kept going up. The trend was unmistakable and significant. All the businesses realised that the proportion of customers they could tap via mobile usage would be an order of a magnitude higher than desktop usage.

The Indian startup scene would change dramatically with the arrival of one previously unknown Lee Fixel of Tiger Global.

In 2009, Lee Fixel would invest an astonishing $10M in Flipkart when it just had $100K of revenue. It would put both Flipkart and India on the map.

Lee quickly became one of the most important start-up investors worldwide. He was known for his speed of making deals, often after brief meetings with entrepreneurs over Skype.

He offered more money and higher valuations than entrepreneurs dreamt of. Fixel’s speed in writing big cheques and clarity in thinking was unparalleled in the ecosystem. He was known for having a transparent, ruthless approach toward entrepreneurs.

The scale and the speed of funding from Lee Fixel forced other VC firms to scale up and offer similar features. Expectedly, VCs now had to compete with each other to do deals faster and quicker than competitors.

Due to the velocity, one of the easy ways to evaluate a startup business model was to judge it with similar companies elsewhere. This gave rise to a whole “X for India wave”.

The trend accelerated the following year when Snapdel was founded and funded as Groupon for India. Initially designed to offer bulk discounts to nearby restaurants and services, Snapdeal soon achieved traction and funding.

In Jan 2011, it raised $12m in Series A from IndoUS Venture Partners and Nexus Venture Partners. By October 2011, Snapdeal had morphed into an online marketplace.

2010 also saw the birth of Zomato. Zomato started as a restaurant listing website for Delhi and then expanded to Mumbai, Bangalore and other cities. In September 2011 Zomato got its series A funding of $3.5 Million from InfoEdge, which Sanjiv Bikchandani ran.

Apart from the focus and the funding for consumer internet startups, the SaaS phenomenon started to take root in the country.

The leader in this segment was Zoho which shifted its focus to become more product led. The availability of cloud services from Amazon and later Google enabled the movement toward productisation, which democratised the space regarding geographic location.

The startup growth continued in the next year with Ola's founding in 2011.

Ola pitched itself as a ride-sharing startup, “Uber for India”. It raised $50k in angel investment, quickly raising $5M from Tiger in 2012. With the ample capital available, Ola started its quest to capture the Indian ridesharing market with a playbook inspired by Uber in the US.

The ecosystem had begun to take proper shape.

Unicorn, Unicorn Everywhere

As India VC formed properly, the domestic ecosystem became professionalised.

Blume Ventures spun out of the Mumbai Angels network. After 5 years, WestBridge split from Sequoia to invest purely in public equities.

Apart from Ola and a few others, the startup ecosystem did not scale as quickly as VCs had hoped.

With a much lower per-capita income than other countries, companies had to deliver immense value at price-conscious points to pick up the slack.

As early as 2011, the professional angels and the VCs realised that although India was a land of high possibility growth here would be more challenging than it was in the US and China.

Despite this India continued to move forwards, soon to hit its next peak. Ailen Lee, introduced the term ‘unicorn startup’ in 2013 to describe a startup with a $1Bn

2013 also marked the emergence of "unicorns" in the Indian startup lexicon. InMobi was the first Indian startup that attained unicorn status in 2011. Flipkart became one in 2012, along with MuSigma. Snapdeal got there in 2014.

Following the creation of horizontal e-commerce players like Flipkart, the period also witnessed the emergence of vertical e-commerce players in the Indian market.

Lenskart disrupted the traditional eyewear market by offering a wide range of affordable eyeglasses, sunglasses, and virtual try-on technology. FirstCry catered to the needs of parents by providing a comprehensive range of baby products and accessories. Nykaa offers an extensive collection of cosmetics, skincare, and haircare products from domestic and international brands.

2014 and 2015 witnessed unprecedented funding and growth within the Indian startup ecosystem. Startups across various sectors experienced a funding boom,

Just like any hot investing market, the funding of hyperlocal grocery delivery companies soared. These startups aimed to bridge the gap between local stores and customers by offering on-demand delivery of groceries and other household essentials.

For instance, Grofers, an on-demand grocery delivery platform, raised substantial funding and expanded its operations to multiple cities across India during this period. BigBasket, another major online grocery player, witnessed significant growth and became one of India's largest online grocery platforms.

SoftBank's entry into the Indian startup ecosystem marked a significant shift in the dynamics of the investment landscape. With its deep pockets and strategic investments, SoftBank quickly became a kingmaker, challenging Tiger Global in terms of influence. The style was similar, large cheques, quick decisions and ruthlessness.

The entry of SoftBank and other global investors injected further optimism and bullishness into the Indian startup scene.

The government's pro-business policies and initiatives, such as "Make in India" and "Digital India," boosted the Indian startup ecosystem, instilling confidence among entrepreneurs and investors.

But a storm was coming.

Move Fast and Get Broken

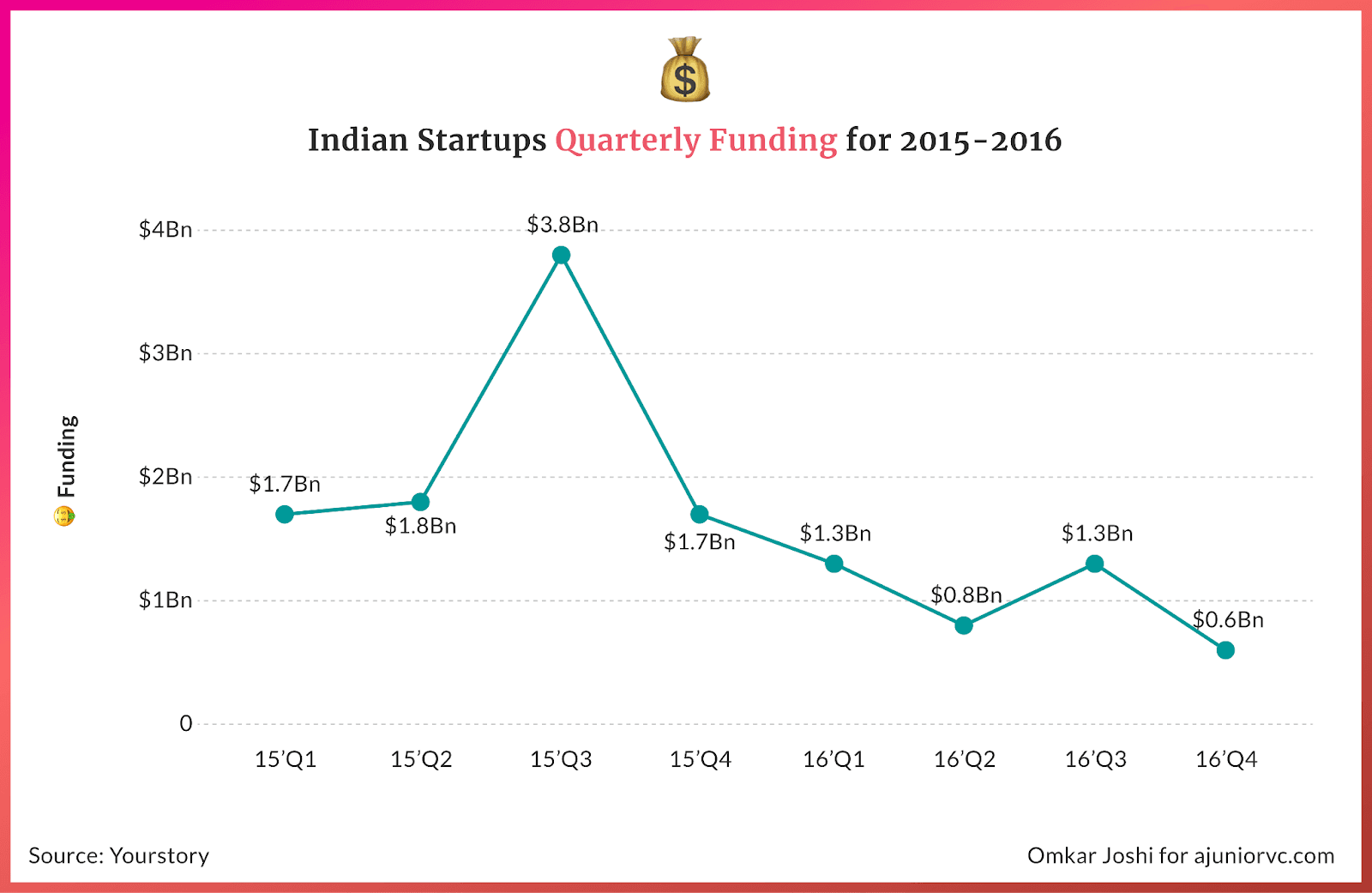

India’s VC ecosystem would hit its second peak in 2014, 8 years after 2006’s explosion

Following the investment high in 2015, the Indian venture capital landscape hit a speed bump in 2016, reflecting the fluctuations in the global economic climate.

Indian startups saw a steep collapse inflow of $4 billion, distributed across 1,040 deals, marking a sharp 55% decline from $9 billion in 2015 and a 20% drop from 2014.

Despite this dip in total investment value, the overall number of deals slightly increased, indicating a strategic shift towards a larger number of more risky early-stage investments.

High-profile investors reduced their pace, leading to a more cautious investment environment.

Tiger, the roaring king of the Indian startup jungle with 38 deals in 2015 and an impressive $1.4B investment over the last two years, entered a quieter phase in 2016, doing 0 new deals and only follow ons

One of the factors contributing to Tiger's more restrained approach was its need for lucrative exits. This cautionary climate marked a pivotal shift in the venture capital narrative, bringing a greater emphasis on sustainable growth.

There would be a collapse in the ecosystem, with carcasses of aspiring unicorns. Housing, TinyOwl and many others would die. The investing ecosystem would seize up, hitting its first major roadblock. The contagion would also engulf India’s storied domestic VC Helion, which would end after a decade of dominance.

Despite this cooling period, several new players emerged on the scene. Entrepreneurship would prove to be eternal.

Startups like Meesho, Moglix, and Sharechat made their debut, displaying the resilience and adaptability characteristic of India's startup ecosystem.

During this period, seed funds like Venture Highway, Stellaris, Pi Ventures, and Fireside Ventures became prominent, ready to take bold bets on early-stage startups.

This fresh lineup of seed funds breathed new life into the startup ecosystem, directing their investments exclusively towards the first stage and amplifying the industry's dynamism.

As the mood was depressed, the VC ecosystem got a steroid boost.

Three monumental events would redefine the startup terrain in India: the disruption by Reliance Jio in the telecom sector, the launch of UPI, and the effect of demonetisation.

Reliance Jio's disruption in 2016 of the telecom industry led to a massive increase in the internet user base, considerably boosting digital businesses. NPCI's introduction of the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) was a game-changer for digital transactions.

Meanwhile, the Indian government's demonetisation move profoundly impacted the financial ecosystem. While it initially caused disruption, it also acted as a catalyst, pushing a large population to embrace digital payment solutions.

As the narrative progressed, the Indian startup ecosystem rebounded, riding on the wave of strategic growth and renewed investor confidence.

Flipkart, the homegrown e-commerce giant, bagged a whopping $2.5 billion from Softbank in August 2017, marking the largest-ever round for a tech startup in India.

Later the same year, digital payments leader Paytm secured $1.4 billion, and ride-hailing platform Ola obtained $1.1 billion, largely thanks to Softbank and Tencent's contributions.

But Flipkart's journey was teetering.

As Amazon aggressively expanded into India with a hefty war chest, concerns regarding Flipkart's ability to keep pace began to surface. Rumours of potential sell-offs and desperate fundraising efforts were seen as stress indicators amidst fierce competition.

Flipkart, then worth north of $10Bn, could not fail. Its failure would take the whole ecosystem down. It would be a pivotal moment in India’s startup history.

But the startup landscape experienced a seismic shift in 2018, in a good way.

Walmart's acquisition of Flipkart for a staggering $16 billion wasn't just an impressive exit, it was a testament to the immense potential of Indian startups. This deal, one of the largest exits globally, transformed the narrative, serving as a beacon of success in the Indian startup journey.

The success story inspired more budding entrepreneurs to leap, fostering increased dynamism in the startup scene.

The massive deal amplified global attention towards India's burgeoning startup ecosystem, drawing in large later-stage investors.

PE firms like General Atlantic would enter the party. It validated the country as a fertile ground for high-value startup investments and escalated the interest of global venture capital firms.

By 2019, India’s startup ecosystem had firmly shaken the ghosts of 2016. With one of the world’s largest exits in the bag, nothing could stop it.

Except for a global crisis.

Pandemic Peaks

The pandemic would first spook investors and startup founders.

Startups would collapse in revenue to nearly zero as India announced its lockdowns in March 2020. VC funding would go to zero in April 2020.

After all, it seemed only possible to invest in a startup by physically meeting them. The industry looked like it was gone.

Instead, within a few months, a zero-interest rate environment fueled a startup party like never before.

COVID in 2020 forced India to go digital. The interest rates being nearly at an all-time low in the US moved FDI in India. The tech crackdown in China would make India even more attractive.

2021 will be the most incredible year in the Indian start-up and VC ecosystem. The year also put India on the world map for the start-up scene.

Over $42 Billion was pumped into Indian start-ups, creating 47 unicorns. To put things in context, from 2010 to 2020, we had 44 unicorns.

The magnitude of 2021 was on another scale. India had crossed the escape velocity and was comparable to the US and China.

The valuations were no more pegged like Indian companies before, instead had American-style valuations; it took only six months to turn unicorn in November 2021 round after raising the first $50 million round in May 2021

2021 was also the year of UPI, reaching Visa and Mastercard scale. India innovated as it needed, different from the timelines of the world.

When it needed a payments ecosystem, it would create one par excellence.

India did not do anything different in 2021. Instead, it was a 15-year journey that was bearing fruit.

India's median age was now 28, and most of the world's young population resided in India. Millennials account for 34% of the country's population, just above 470 million. In context, that is over twice Pakistan's population.

This also meant we had excellent software talent just taking off and too many engineers ready to build from India.

Investors' bets for decades had paid off. India’s software exports were now higher than Saudi Arabia’s oil exports. The capital constraint that was seen in the previous years was gone.

Three pillars for an economy to explode – Talent resource, Governance structure, and Capital infusion.

While it is supposed to be the governance structure leading the way for the other two to follow, the latter took charge from India.

India would also see exits being bogged for years over “no exits”

With over 250 acquisitions and over 11 IPOs, InfoEdge made a blockbuster outcome with Zomato. Elevation Capital would get a big one with PayTM, and Accel would see Freshworks raising the India flag at Nasdaq.

Tiger and Sofbank were seen as taking Indian startups to the finish line by IPO-ing just as they did in the other two big economies in the previous few decades - US and China.

Just when things were seen as that, things were changing globally

Fearful Present, Exciting Future

Russia would invade Ukraine, sending inflationary shocks into the ecosystem.

The markets crashed globally due to the jack-up of interest rates to combat inflation. US public markets had never seen a crash, much so that even the 2008 crash was seen as lesser wealth destruction on the market cap scale.

Global investors also started pulling money out of China. Meta lost nearly 700 billion, and Alibaba and Tencent lost nearly 500 billion.

While the number of unicorns and funding had dropped considerably, it was India’s second-biggest year. VCs were still not wholly closing the tap yet.

We still had 24 unicorns in 2022. Over 25 Billion US dollars were pumped into the startup ecosystem.

It took the whole world to collapse and flip upside down first for the Indian tech ecosystem to realise there could be a funding winter around the corner.

India’s ecosystem had effectively crossed its 3rd peak in 2021.

At the same time, investors from India were raising record dry powder from their LPs, and on the other, the number of active micro VC funds in India climbed to more than 80 in 2022, up from approximately 65 in 2021

As India exited 2022, governance started to become a big issue. In good times, the incentives of founders and investors align. In bad times, if incentives don’t align - skeletons fall out of the closet.

Many Indian companies would see irregularities, many had to tussle with high valuations, and many were unsustainable due to a lack of business models. Many startups lined up for an IPO were now contemplating. OYO, Snapdeal, Byjus and more had to stay longer.

2023 would be the year of tightening, a feeling like this was the end of the ecosystem.

7 months in, we have seen precisely 0 unicorns, and funding taps have closed. We have gone back to basics, and VCs have become more conservative than ever before. Even angels had closed the tap

BYJUs, the Flipkart scale beast of 2023, tottered heavily, slashing valuations from $22Bn to $8Bn. But India’s ecosystem was not as young as 2018, likely containing any negative impact of one company.

Seeing the deep history of Indian venture, we will see that this is the end of yet another cycle. The ecosystem looked like it was dead in 2009. It looked like it was dead in 2016. It seems dead in 2023.

But the truth is, as you would have realised by now, it is yet another peak.

After 7 years of epic growth, we are entering a new consolidation phase. As you can see, 2007’s peak wasn’t hit till 2014, 7 years later. Similarly, we do not expect 2021’s peak to be hit anytime soon.

But it will be hit, and that is precisely because India’s arc of progress continues.

Governance will become tighter. India’s unicorns will focus on cleaning up the house and reaching profitability. Valuations will rationalise. These are all signs of a now large ecosystem maturing.

More importantly, India’s investor ecosystem will size itself rightly.

India is a unique country with few overcapitalised companies and many undercapitalised companies. The proliferation of funds will allow more companies to be funded while ensuring the most significant few are not overfunded.

Startups will certainly go up, investors will undoubtedly finance more.

Equity is a claim on underlying cash flows. Cash flows are generated from a growing economy. India is expected to grow the fastest this year and for a few years. As global geopolitics weakens America and China, this could be our decade to shine.

Entrepreneurship will be the engine taking us forward, as it is eternal regardless of cycles.

As 2016’s birth of so many present unicorns shows, 2023 will create many. They will be crowned in the future. As long as India grows, there is no stopping the startup ecosystem.

This is likely to be the most critical decade in India’s history as we likely get promoted as a global superpower. While it seems like a period of fear, there should be nothing less than excitement.

Be fearful when others are excited and when others are fearful.

As history shows, India’s VC ecosystem has not peaked. It is yet another peak that will eventually be scaled.

Writing: Nilesh, Parth, Samarth, Shreyans, Tanish and Aviral Design: Omkar and Blair