Mar 17, 2024

Can 25,000 Cr Narayana Turbocharge India’s Low-Cost Health Innovation?

Healthcare

Brand

IPO

B2C

Profile

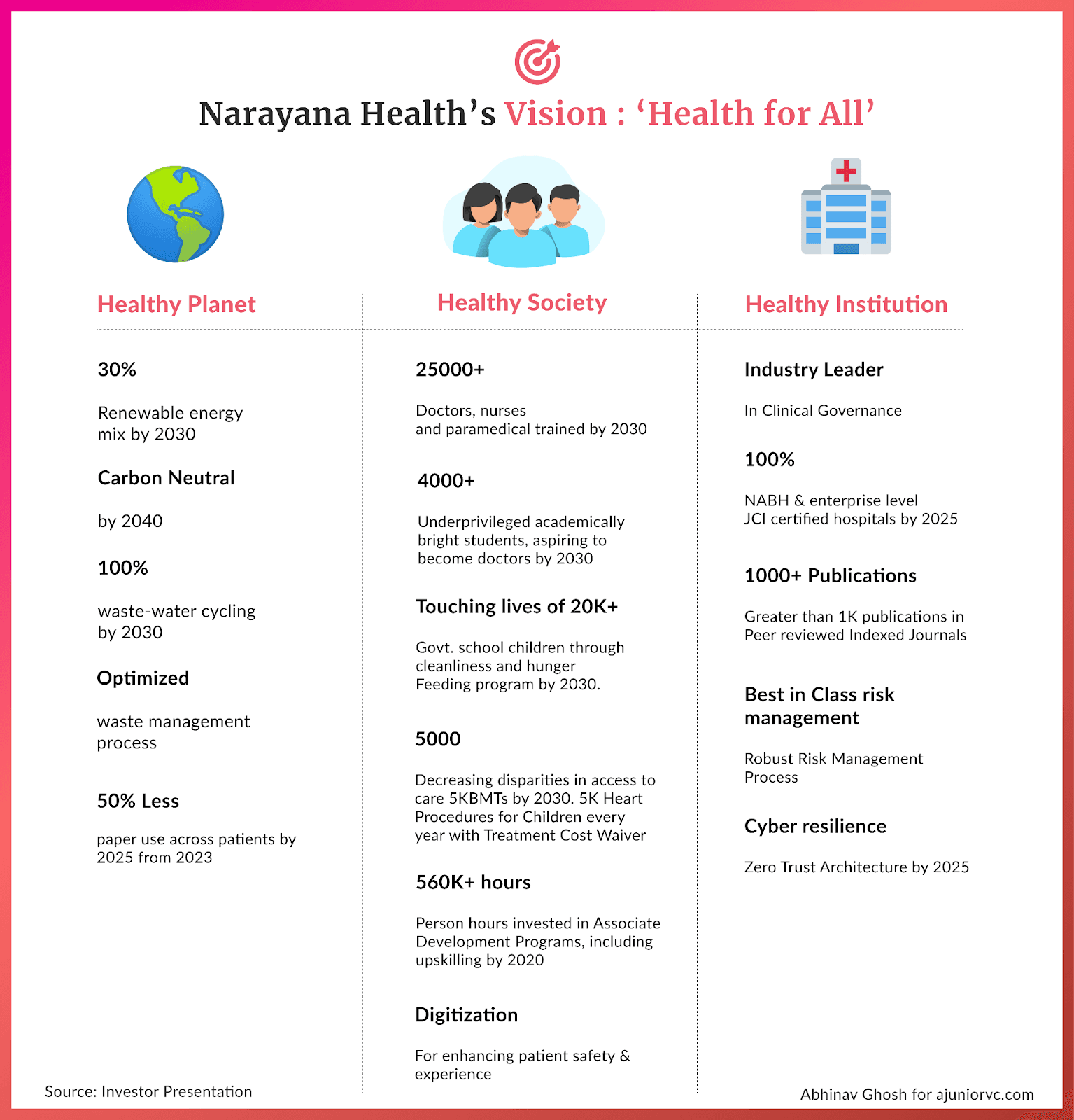

Last fortnight, Narayana set the ambitious aim of dissociating health from wealth, on the tailwinds of a year, it breached ₹27,000 Cr in market cap.

Big Heart

Dr Christiaan Barnard carried out the first heart transplant surgery in 1967.

A young boy in his fifth grade in Mangalore was so inspired by this event that he knew in his heart what he wanted to become. However, to become a heart surgeon, the young Dr. Devi Shetty realised that he needed to become a doctor first.

He graduated from Kasturba Medical College in Manipal with an MBBS in 1979. At the time, India lacked opportunities to train a heart surgeon. He then went to England to join Guy’s Hospital in London, considered one of Europe's best cardiac centres.

He returned from Heathrow to Howrah in 1989 and set up the cardiac surgical unit at BM Birla Hospital in Kolkata. He was the only heart specialist in the city.

In one of those early days of his career, Dr Shetty received a call from a patient who requested a home visit. Although surgeons didn’t do home visits, a reluctant Dr Shetty still did the visit.

His patient was Mother Teresa.

Once in a while, when Mother Teresa was admitted to the hospital, she would follow Dr. Shetty during his rounds in the pediatric ICU. In her words, when God created these kids with a hole in their hearts, he realized his mistake and sent Dr. Shetty to Earth to fix those mistakes.

This accolade redefined the way Dr Shetty approached his profession.

Dr Shetty soon realised the stark difference in his practice in India compared to that in the UK. Less than 1% of the patients he attended in India could afford heart surgeries. Most of his patients were so malnourished that their wounds would not heal after the surgery. This was alarming since Indians are three times as likely to suffer from a heart attack as Caucasians.

The average age of his patients in England was 60, whereas in India, it was 45.

By the 1990s, instead of a young man bringing his father for treatment, the old father would bring his young son for a heart operation. It was a silent epidemic. India needed two million heart surgeries a year, but less than a hundred thousand surgeries were performed. Unless the patients could afford the surgeries, Dr Shetty would not have a practice.

Dr Shetty took it upon himself to bring cardiac surgery to everyone. Narayana Hrudayalaya was born in 2000 as a 280-bed hospital in Bangalore. Dr Shetty’s father-in-law provided him with the initial seed capital needed to set up the facilities on the hospital premises.

His only condition was that he never refuse surgery on any child suffering from heart disease.

Bypassing Big Costs

By the mid-2000s, it was clear fixed costs formed the lion’s share of any hospital's expenses.

Building and maintaining the hospital infrastructure, blood banks, and laboratories with machines for CT scans, MRI, and PET scans were expensive. To provide care at lower costs, building hospitals with 100-200 beds would not do the trick. They needed to be built at scale so that economies of scale could kick in.

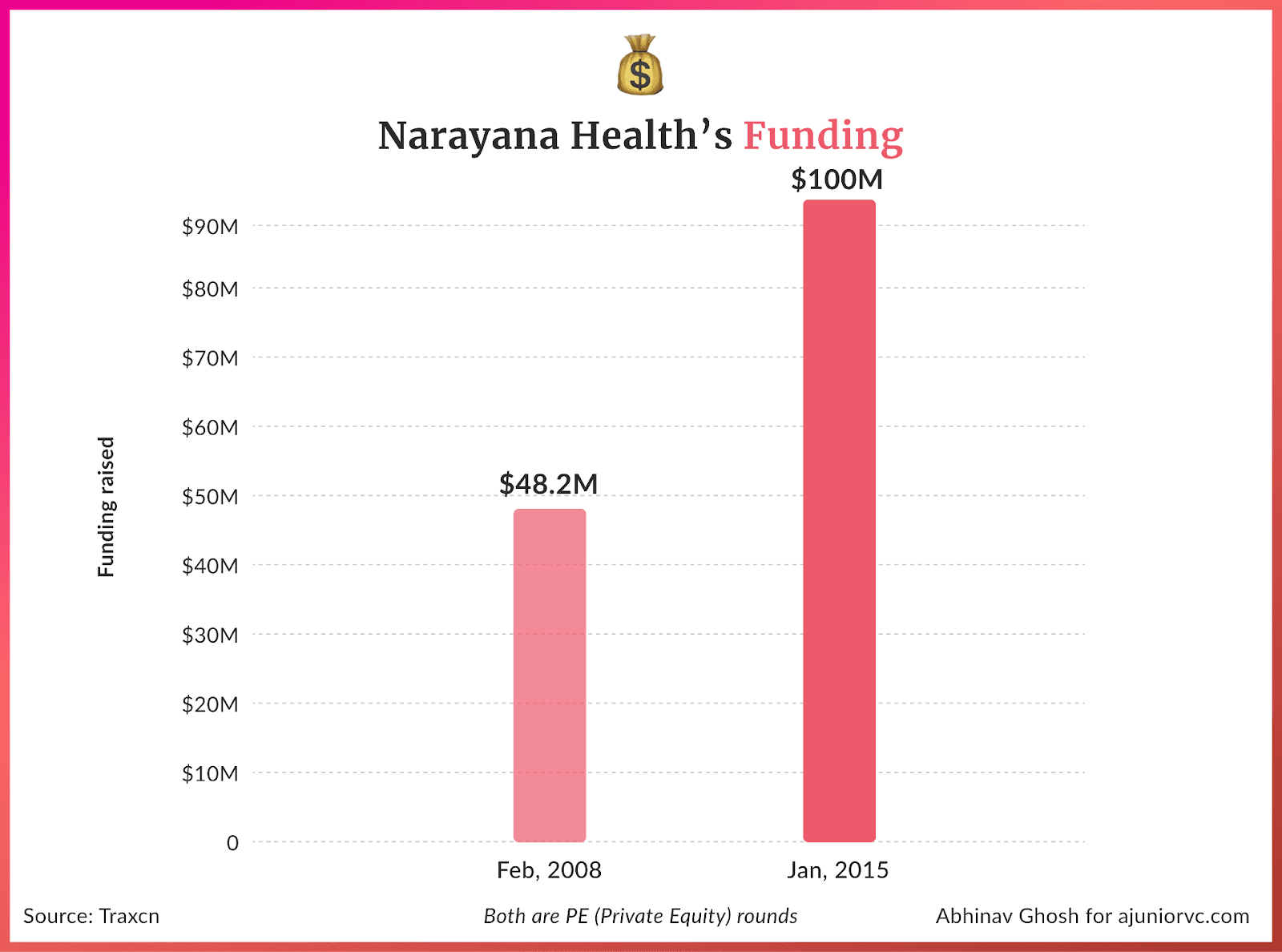

Dr Shetty cracked the code for low-cost, affordable healthcare for the masses similar to Henry Ford scaling his factory to produce automobiles. Narayana would raise its first round of financing of ₹200 Cr at a ₹1,500 Cr valuation to scale.

A heart surgery that costs $200K in the US would cost only $1400 in India at any of Narayana Hrudayalaya’s hospitals, made possible through Dr Shetty's “Walmart-isation” of care. Soon after the first 260-bed hospital, Narayana started to build, keeping scale in mind.

Narayana’s massive hospitals were built on 5-7 acres of land and could house 500+ beds. Advanced machines and equipment are bought in bulk and used 24/7. The hospital should have many outpatients, which is possible only if the surgeries are affordable.

In addition, doctors and nurses at Narayana worked six days a week, compared to five days a week when healthcare frontline workers work at US hospitals. The average hours that doctors work in India are also almost double those of their US counterparts.

Skilled labour is much more expensive in the US, where 65% of the hospital’s revenue goes towards salary. In India, the equivalent number is 20%.

Combined with the money budgeted for litigation spending and that set aside to pay for malpractices, the hospitals in the US need help to innovate within their current system. It eventually became a business with too many people, following many rigid and archaic processes.

By 2010, Narayan Health had reached the scale of almost 4000 beds with more than 12 hospitals. The chain was staring at a massive opportunity.

Pacemaker for Progress

Treatment of cardiovascular diseases in India was poised to reach $10B in India.

Surprisingly, at Narayana Hrudayalaya, 30% of the heart surgeries performed were on babies. India produces 20 million babies a year, the largest in the world.

One out of every 140 babies born in the world is prone to have heart disease at birth. So, there are between 600-1000 babies that are born every day in India with a dysfunctional heart. If these children are operated in the first few days after their birth, they can be cured permanently.

However, along with constraints of treatment capacity, Indians cannot afford a $200K surgery.

Dr Shetty realised that if the treatment costs are brought down to <$2000, families could scrape together the fees to save their child, in case it is a male.

However, that threshold is still not low enough for daughters. That’s why Narayana hospitals fully subsidise the treatment costs for girl children through the aid and donations they receive.

In 2012, Dr Shetty roped in the state-run Insurance Karnataka Milk Federation to sponsor insurance for their network of milk-producing farmers.

The initiative was called Yashaswini and was one of the earliest micro-insurance programs to run in the country, with premiums as low as 11 cents/month. The idea was to price at the cost of a locally available cigarette. The goal was to drive awareness amongst the villagers to quit smoking and reinvest that money into buying health insurance for their families.

Narayana's decade of existence had become transformational for Indians, especially those at the lower end of the income spectrum. In the very same year, Devi Shetty would be awarded the Padma Bhushan for his efforts in bringing low-cost healthcare to India.

Narayana’s healthcare business for everyone was also beginning to reach real scale.

Pumping Up Globally

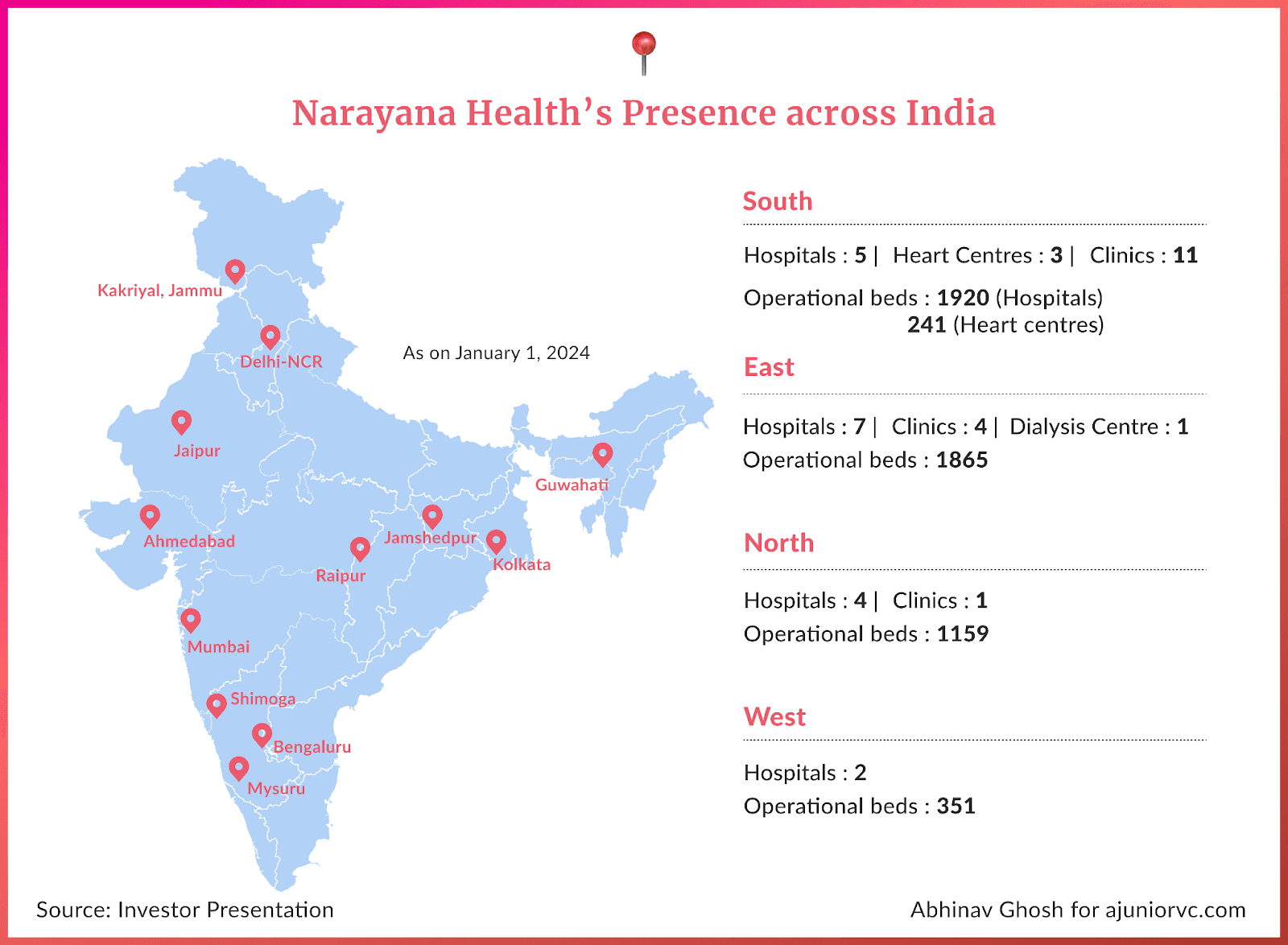

By 2013, Narayana Health was operating 18 hospitals spread across 14 cities in India.

Revenues touched a whopping Rs. 827 Cr, with a growth of 200 % over the past five years, and EBITDA margins reached a healthy 13%.

Narayana Health followed a multi-pronged strategy to fuel its fast growth, aiming to maximise the efficiency of and returns on capital employed.

Narayana would initially own and operate hospitals outright. However, establishing a 300-bed specialty hospital in major cities costs anywhere between Rs. 150 – 200 Cr. This would not be the most feasible option to achieve high-scale growth.

It adopted a second model to scale – revenue sharing.

Through an ‘asset light’ approach, Narayana Health found the right partners who would invest in and own capital-heavy fixed assets, including land and buildings. This freed up Narayana Health’s capital and administrative bandwidth for owning and maintaining medical equipment.

Instead of their investments, partners would have a claim on the hospitals’ revenue.

The third model was also collaborative – this time, with governments. Its first low-cost hospital in Mysore was constructed in 2013 with the Government of Karnataka having a 26% equity share, and the model was repeated with the government of Assam to build a hospital in Guwahati in 2015.

The fourth model involves operating third–partyowned hospitals and cardiac centres attached to third-party hospitals on a management fee and/or a lease basis. These efforts were supplemented by acquisitions occasionally.

Narayana’s Health ambitions were not just limited to India. It wanted to leverage its healthcare expertise, strong focus on quality, and cost-efficient operating model to target new markets.

In 2014, it invested $100 million in establishing a 104-bed hospital in the Cayman Islands, a short flight from Miami. The Cayman Health City aimed to be a disruptor, pushing the expensive US system to innovate.

On average, Narayana Health cardiac centres performed 40 heart surgeries for less than $1600 each, less than 2% of the cost of a similar operation in the U.S.

The American healthcare market was ripe for disruption, and Narayan Health was ready to jump in. To execute its vision, it entered into a joint venture with an American not-for-profit healthcare group, Ascension Health Alliance.

Narayana Health raised Rs. 300 Cr in 2015 to fuel its domestic and international ambitions, valuing the company at around INR 3,000 crore.

Backed by strong ambition, multi-pronged growth models and international funding, Narayana Health grew to a network of 23 hospitals in 2016, with 5,600 operational beds. It enjoyed considerable domination and brand presence in two geographical clusters – Karnataka, which had 2,344 beds, and East India, which had 2,270 beds.

But Narayana Health was just getting started. Its target? 30,000 beds.

Racing to Capture India

Having firmly established a presence in the South and East, Narayana Health set its sight on the North and the West.

But growth was not being chased for growth’s sake. Scale was Dr. Shetty’s next step towards solving the problem he had founded Narayana Health for—providing accessible, affordable quality healthcare for the masses.

Or, as the founder put it in aninterview - size for social impact; size for social sustainability.

Economies of scale, centralised supply purchases, and high utilisation rates for medical equipment allowed Narayana Health to provide lost-cost treatments yet be profitable.

But for Narayana Health to chase more growth, it needed more money.

To achieve 30,000 beds, Narayan Health turned to the public markets and launched an offering, raising INR ~600 Cr and also providing its investors with an opportunity to exit. The issue was oversubscribed eight times, with its shares debuting with a healthy premium of 30 percent.

Flush with funds, it forayed into the North in 2016 by commissioning a super speciality in Jammu, acquiring an under-development multi-speciality hospital in Gurugram, and managing the operations of a third-party multi-speciality hospital in Delhi.

In parallel, it made inroads in the West by commissioning a pediatric hospital in Mumbai. Its long-term plan was to make Delhi and Mumbai the primary hubs for its north and west clusters.

By 2018, Narayana Health had 51 facilities, with a cumulative capacity of 7,181 beds, and an increase of ~30 per cent in just two years.

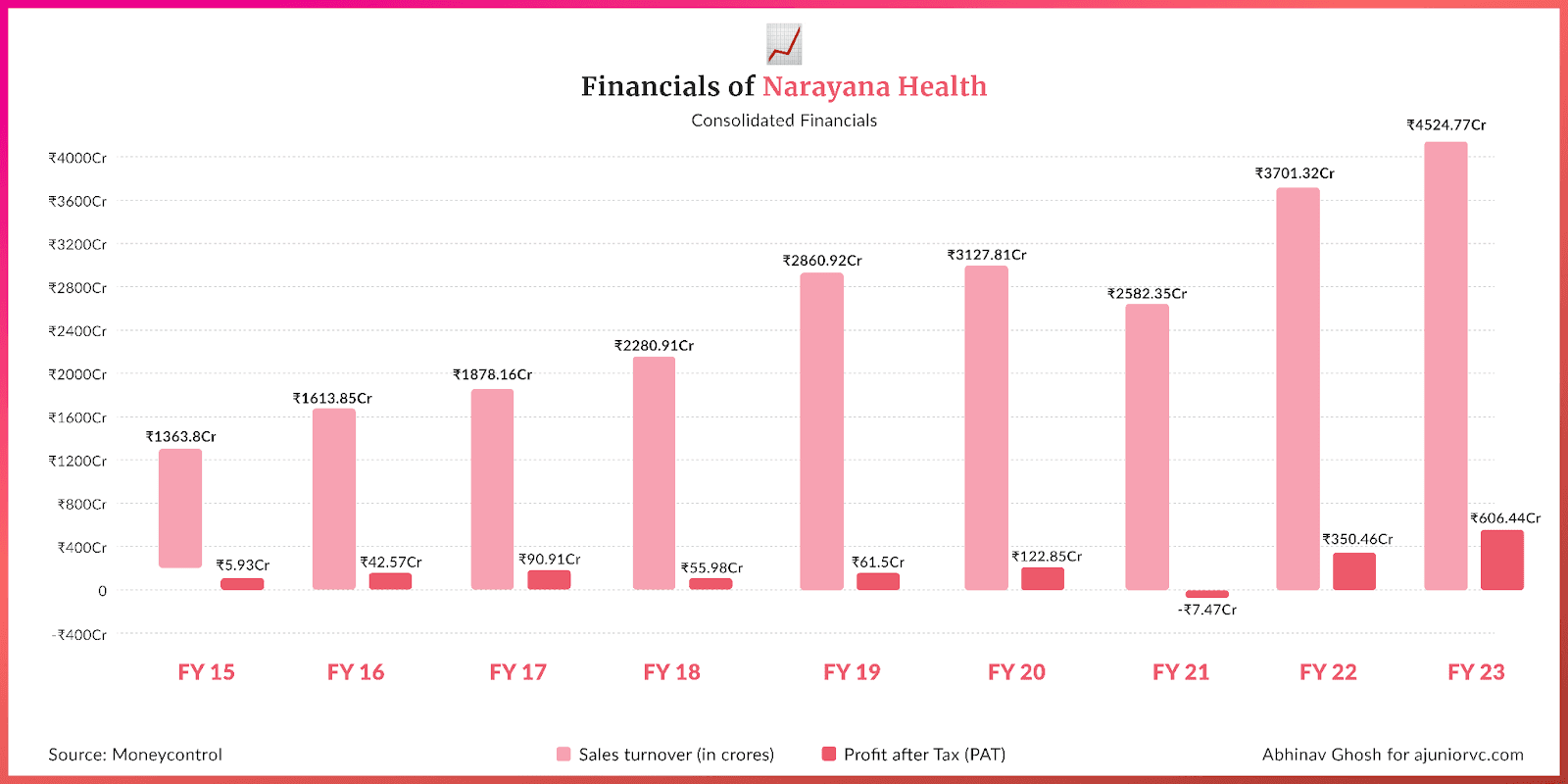

And its numbers reflected a similar growth. Revenue grew from ~INR 1,600 Cr. to ~INR 2,300 Cr.– a growth of a ~40 per cent – in this period. EBITDA margins fluctuated between 10-13 per cent, growing similarly. ~40 per cent of its revenues were sourced through cardiac science services, indicating improved diversification of specialities

The Cayman facility’s operating leverage came into play due to a 79% CAGR between FY15-18, yielding EBITDA margins of 13.5% and first-ever profits of USD 1.2 million in FY 2018.

Narayana had scaled to global markets and had a heavy presence in all corners of India. To understand how it was growing rapidly, one needed to know how it kept costs low.

Bottomline of the Business

Narayana’s model is built with a laser focus on optimising costs and improving efficiency.

Unlike many hospitals that run top-down, surgeons are treated as business owners. The impact is economics improves bottom up.

Surgeons at Narayana Health receive a daily profit and loss (P&L) statement detailing the costs and revenues for each surgery performed. This granular financial data allows surgeons to identify areas for cost optimisation.

For example, they may find opportunities to reduce the cost of surgical supplies or shorten the length of hospital stays. The P&L statements create cost consciousness and accountability among the surgical teams.

Narayana Health also cross-subsidises to make care more affordable by charging higher prices to wealthier patients and medical tourists. Foreigners coming to Narayana Health for treatment pay more than local patients

This enables the hospital to offer discounted rates to lower-income patients while remaining profitable. About half the patients pay full price, while the other half receive subsidised care.

As part of the cost consciousness, efficiency is paramount at Narayana Health's hospitals.

The average Narayana cardiac hospital performs 40 heart surgeries daily at less than $1,600 per case, just 2% of the U.S. average.

All this is enabled by the way Narayana Health reduces costs is through economies of scale.

The health system performs an extremely high volume of procedures—around 40 daily cardiac surgeries. Specialist surgeons perform 400-600 procedures annually, compared to 100-200 in the U.S., enabling them to hone their skills.

High patient volumes allow Narayana to negotiate better prices with suppliers and spread fixed costs over more patients.

Narayana utilised a "production line" approach where surgeons focused solely on surgery while other clinicians handled pre-op, post-op and non-surgical tasks.

Importantly, Narayana's low costs do not come at the expense of quality. Mortality rates within 30 days of cardiac surgery are 1.4% at Narayana compared to 1.9% for the U.S. average.

Infection rates are also lower than international benchmarks, which are enabled by experienced surgeons performing high volumes of standardised procedures.

As Narayana Health expands with new hospitals across India and internationally, it aims to increase access to affordable, high-quality tertiary care. Its model of combining innovative cost optimisation, cross-subsidization, and efficiency could provide valuable lessons for hospitals globally.

Narayana had made rapid strides as a business as it closed the decade.

Missing a Beat in COVID

In the run-up to 2019, Narayana Health grew rapidly.

It scaled its hospital network, increased its focus on tier 1 cities, grew its international presence, undertaken sustainability initiatives, launched innovative healthcare access programs, and refreshed its brand identity. Narayana saw instability in profits due to higher depreciation and amortisation expenses and finance costs related to new hospitals and expansion.

Narayana Health saw strong revenue growth of 25.4% in FY19 and a 14.2% profit increase. EBITDA margins were healthy at 11-12% in FY19, as the operating revenues increased, driven by volume growth across the network hospitals.

Nearly 60% of revenues were spent on operating and direct expenses; employee costs accounted for 26%. Depreciation and finance costs also impacted 8.1% and 3.7% of revenues, respectively.

Growth looked unbeatable. But then came 2020.

The 2020 COVID pandemic affected every sector of the economy, and Narayana Health was not spared either.

In the first quarter of FY2020-21, it posted a net loss of ₹31 crore ($4.2 million) due to the impact of the pandemic-induced lockdowns and travel restrictions, which affected the main revenue source of elective surgeries and medical tourists.

Profit after tax was Rs. 119.5 crore, compared to Rs. 124.1 crore in FY19. The reason for flat profits was that the loss from the impact of COVID-19 in March 2020 offset the revenue and profit growth seen in the first three quarters.

It got even harder in FY21.

The consolidated total operating income declined by 8.3% YoY to Rs. 2,904.7 crore. Loss after tax was Rs. 81.7 crore compared to a profit of Rs. 119.5 crore in FY20.

To address healthcare needs during the pandemic, Narayana Health launched dedicated COVID-19 treatment facilities: a 100-bed COVID quarantine facility in Bengaluru in partnership with Infosys Foundation and a 100-bed COVID ICU facility at Narayana Health City in Bengaluru with Goldman Sachs.

Dr. Devi Shetty was appointed to the National Task Force to facilitate India's public health response to COVID-19. Narayana released advisories for the public on staying healthy during lockdowns and managing post-COVID complications

As a result of the losses, Narayana Health had to temporarily pause some of its expansion and investment plans during the peak pandemic years. However, as healthcare awareness grew post-pandemic, the company restarted pursuing an ambitious expansion strategy, especially in the Caribbean region.

This is reflected in the fact that in FY22, the Profit after tax was Rs. 273.4 crore compared to a loss of Rs. 81.7 crore in FY21. A strong recovery post-COVID-19 impact, higher occupancy, an increase in elective procedures, and international patients drove this.

As Narayana recovered, its competitors did, too.

Temperature Check

Narayana Health faced intense competition as it entered the new decade.

Competition came from large hospitals like Apollo Hospitals, Fortis Healthcare, Max Healthcare, AIIMS, Aster DM Healthcare, and diagnostic chains like Dr Lal Pathlabs.

Cost in each hospital was a big differentiating factor for Narayana, but it went a few steps further on this playbook to scale.

Narayana Health followed a hub-and-spoke model. It established a network of spoke hospitals in tier 2-3 cities that feed into its hub hospitals in major metros. This allowed Narayana to expand its reach while keeping costs low. The spoke hospitals handled more routine procedures, while complex cases were referred to the hubs.

In addition, Narayana had one of the world's largest telemedicine networks, connecting 800 centres globally, including 53 locations in Africa. Narayana can each patients in remote areas by not investing in physical infrastructure.

Narayana Health announced plans to expand its footprint and cater to the underserved Eastern India market in 2020-2022 by setting up a 1,000-bed advanced speciality hospital in Kolkata. This will be one of the region's largest hospitals and offer advanced tertiary care services. The Kolkata hospital will serve as a hub for Narayana's network of spoke hospitals in Eastern India.

Narayana Health also designed micro-insurance programs to improve healthcare affordability and access. In partnership with the government of Karnataka, Narayana piloted a micro-insurance scheme in which a large group of people paid small regular premiums to cover a set of procedures.

Narayana Health launched its health insurance subsidiary based on what was learned from this pilot.

As it entered 2023, since its first healthcare service in Bangalore, which had 225 operational beds, it reached had a chain of 24 primary hospitals.

It caters to major Indian cities such as Bangalore, Delhi, Gurugram, Kolkata, Ahmedabad, Raipur, Jaipur, Mumbai, and Mysore, with an international subsidiary in the Cayman Islands.

Focused on seven heart centres and multiple primary care facilities across India, it serves 7,000 beds.

During Narayana Health's inception, approximately 2.4 million Indians required heart surgery annually. Nevertheless, only 60,000 could be treated because of high costs and limited providers.

That gap looks much smaller, and everyone wants it to reduce further.

Shot in the Arm

The government's latest effort is to reduce healthcare costs in 2024

An action taken via a PIL requires a regulatory fee structure at hospitals. Regulations are now being implemented to standardise rates across hospitals.

Narayana will continue establishing its low-cost and quality healthcare philosophy from its combination of healthcare and tech. It is moving towards an omnichannel presence, allocating a budget of total capex spend of Rs 2,000 Cr for FY23 and FY24.

With the simple insight that doctors use their phone up to 200 times daily, they have built out the Narayana Health App. Doctors can now monitor patients' conditions through smartphones and collaborate with their nurses and team.

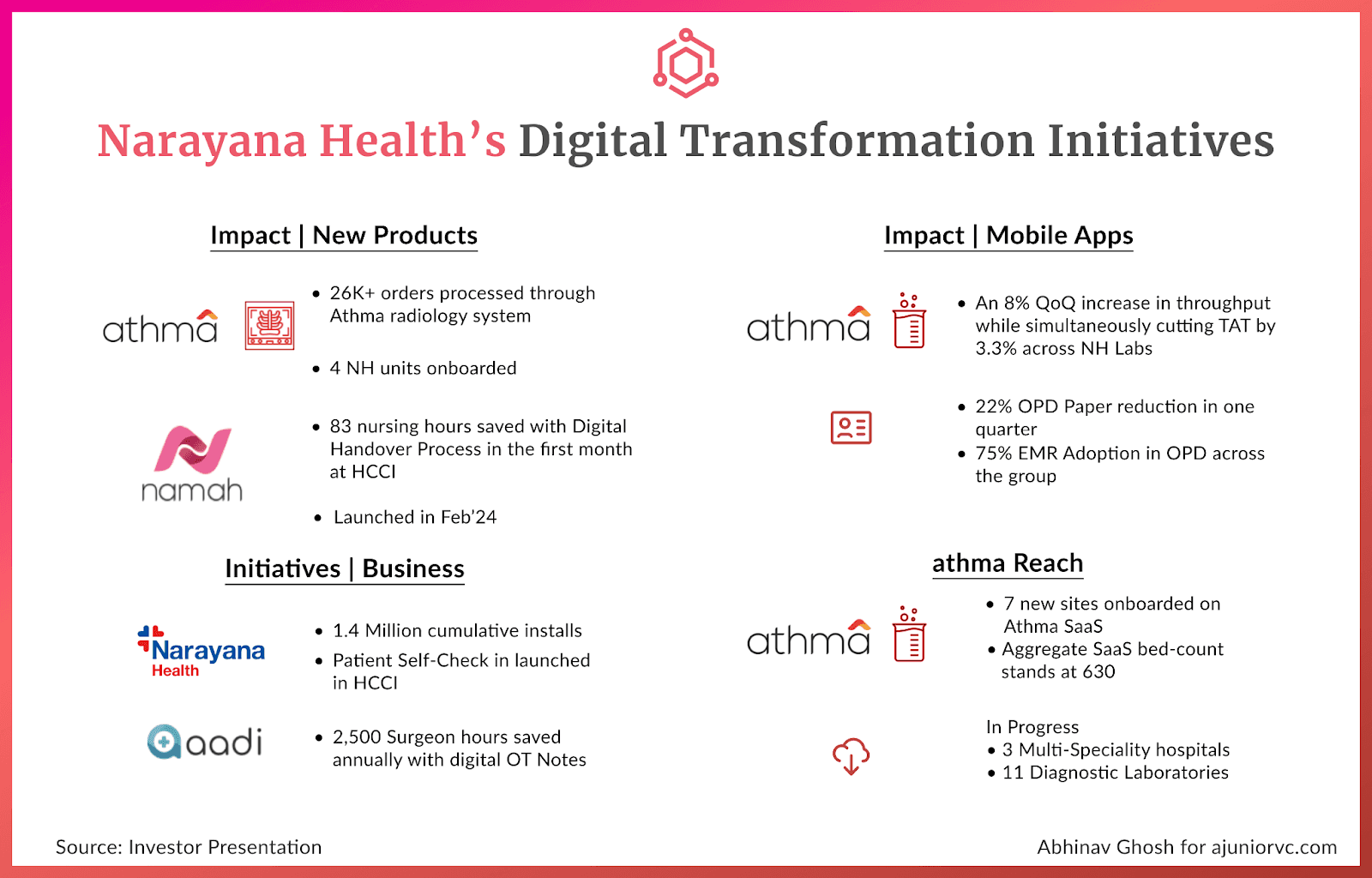

The impact is already seen and compounded as their discharge turnaround time has reduced by over 52 per cent. Another area of impact is outpatient consultations. Delays in outpatient care have dropped by 32 per cent, and waiting times have been reduced by 14 per cent. Online appointments have seen an increase of up to 3.5 times. It has also introduced its homegrown records management system, Athma.

Narayana reported a 34.3 percent y-o-y increase in net profit to ₹226 crore in Q2 FY24, with a consolidated revenue surge of 14.3 per cent to ₹1,305 crore. Higher patient volumes across units and overall growth are leading to good numbers in both India and Cayman Island.

Narayana Health is also foraying into health insurance and has acquired the necessary licenses from the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI). The idea is to tap into customer demand in the health insurance sector while solving for lack of expertise and penetration of health insurance in India by innovating customer-centric products.

The health insurance business is the largest segment in the non-life insurance industry, contributing 38% in FY23.

In January 2024, Narayana Health received final approval from the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) to launch a health insurance business. Narayana Health aims to provide patient-centric insurance plans in three categories - entry-level, mid-level and comprehensive coverage.

By combining its prowess as a low-cost, high-quality healthcare provider with an integrated insurance offering, Narayana Health aims to further its mission of accessible healthcare.

20 years of building a huge healthcare brand is now beginning to pay off. Narayana has built both distribution and trust in an increasingly large market. Up-selling and cross-selling healthcare-related products is now going to be a lot easier.

A dream to fix hearts in 2000 is now ready to scale, as Narayana aims to expand its low-cost approach to quality care not just in India but worldwide.

Writing: Keshav, Anisha, Chandra, Raj, Shreyas and Aviral Design: Abhinav and Stability