Feb 18, 2024

Will India Stack 2.0 Make $100Bn Indian Fintech a Global Export?

Payments

Lending

Finance

B2C

B2B

Platform

Last fortnight, India successfully launched UPI in Mauritius and Sri Lanka, hot on the heels of ONDC completing 5.5M+ monthly transactions and Paytm’s regulatory intervention.

Identity to a Billion

Following 1999’s Kargil war, the Review Committee 2000 identified the need for ID cards.

The project was for India's border areas to enhance national security, leading to the Multi-purpose National Identity Cards (MNIC) proposal.

By 2003, under the Vajpayee administration, amendments to the Citizenship Act introduced the MNIC. However, the UPA government's takeover in 2004 shifted the project's focus towards aiding the impoverished, culminating in the distribution of the first MNICs by 2007.

The project became the National Authority for Unique Identity (NAUID) under the Planning Commission.

During the same period, India’s GDP grew at an average of 7.5%, becoming one of the fastest-growing economies globally. Yet, it lagged in internet usage and banking, with less than 10% and 15% of the population engaged, respectively, compared to 30%-50% in other major developing economies.

The problem needed to be solved, the fastest way was to go digital. But to make things digital, identity was required to be established.

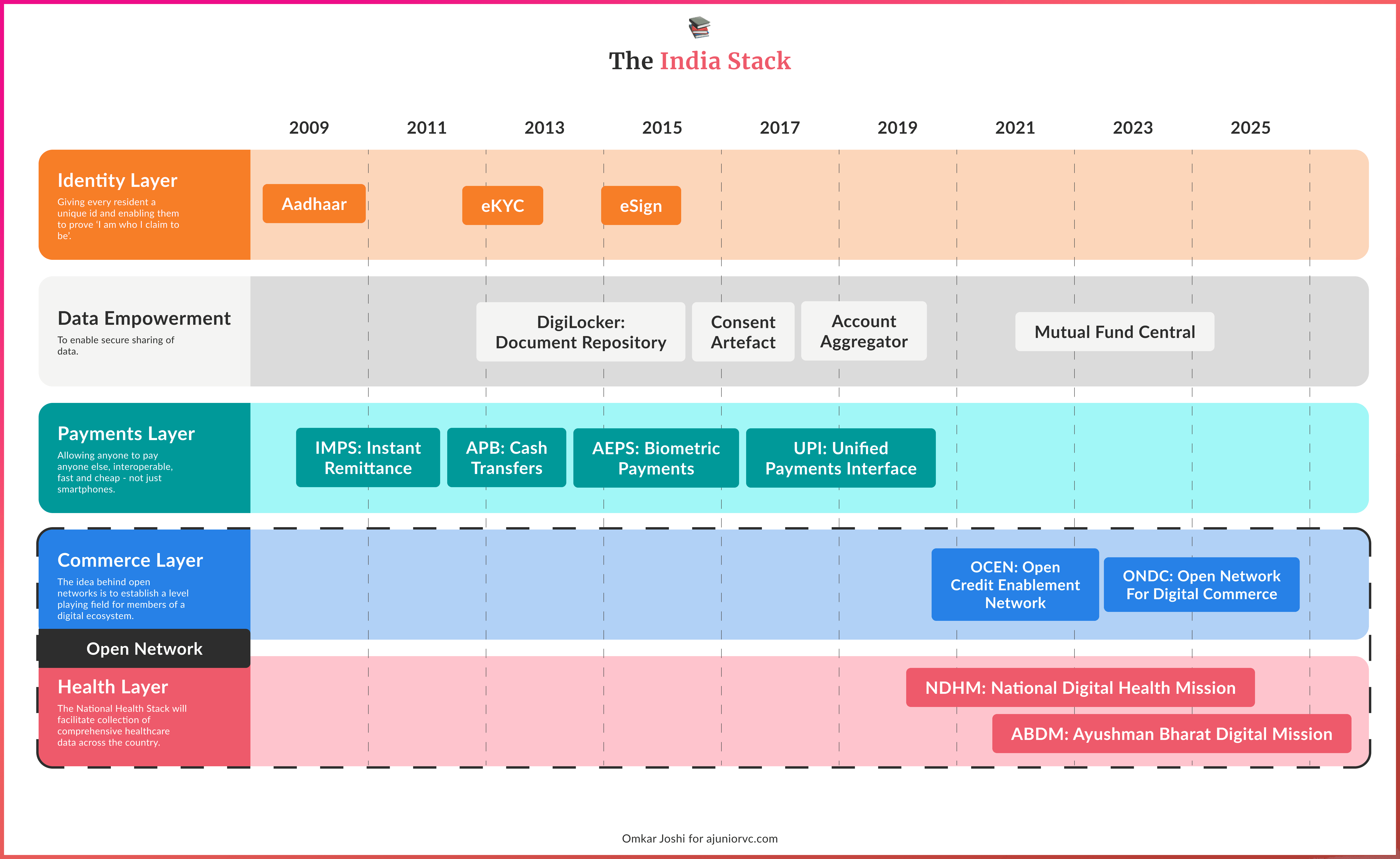

The erstwhile NAUID was transformed into UIDAI in 2009.

Establishing the UIDAI marked a pivotal move towards digital identity verification to facilitate direct and secure delivery of government services and subsidies, aiming to mitigate past inefficiencies and fraud.

It took off.

By 2014, over 50 cr enrolled for Aadhaar, significantly improving financial inclusion through the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, which leveraged Aadhaar for bank account openings, increasing account penetration to over 50%.

Aadhaar-linked Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) minimized welfare fraud, with cash transfers increasing 20-fold and beneficiary numbers doubling by 2015.

Services started using Aadhaar for identity checks. This included mobile connections and banking services. Aadhaar Enabled Payment Systems (AEPS) were introduced, allowing transactions with Aadhaar authentication.

Acknowledging the transformative power of technology to vault into a technologically advanced future, the Indian government rolled out an Open API policy.

This strategy aimed to make government data and services widely accessible to everyone.

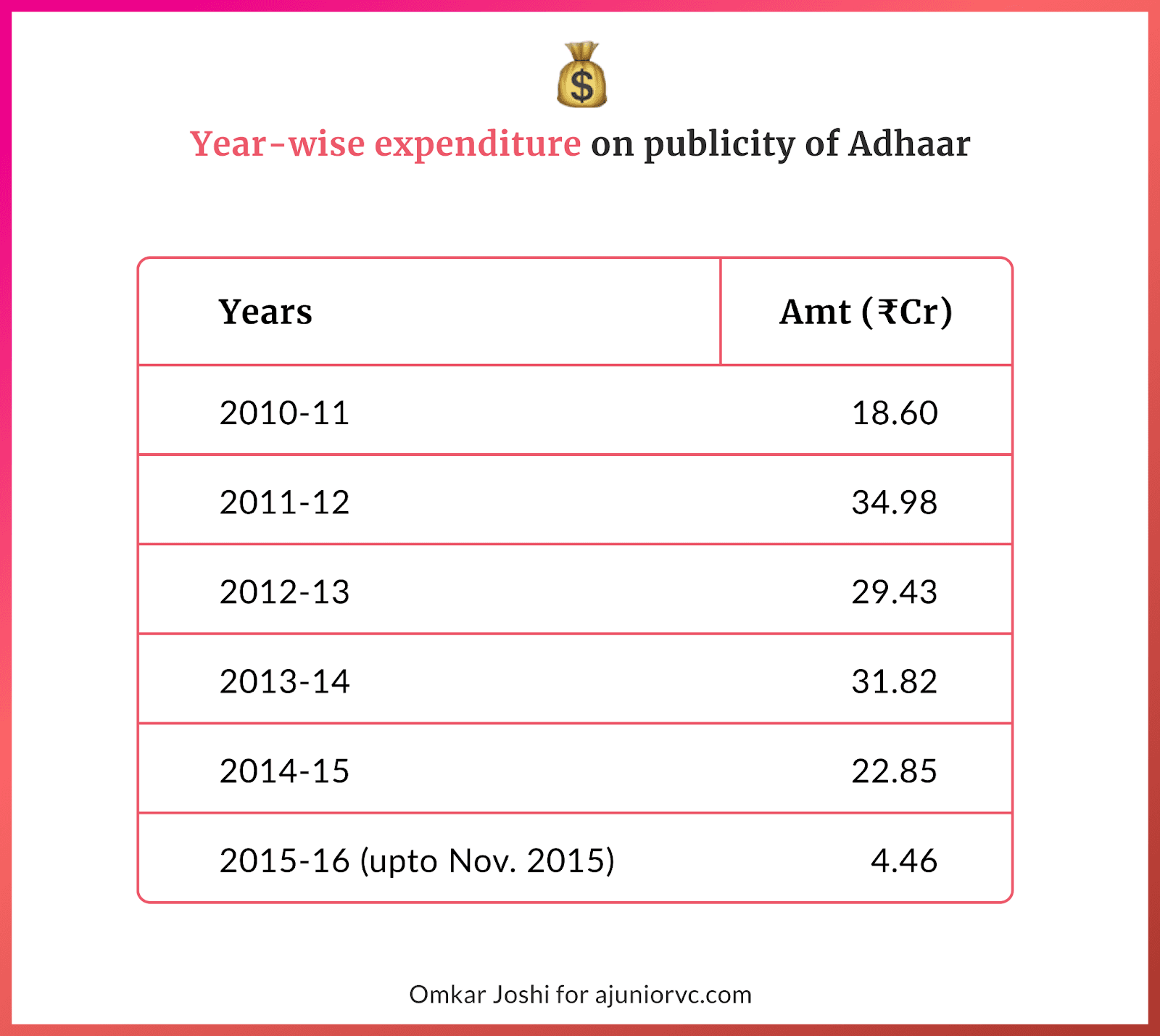

It would hardly be an exaggeration to say the government was ahead of its time.However, certain sections of society were sceptical about privacy.

The Supreme Court of India directed the government to promote that enrolment in Aadhar was not mandatory.

The ads did exactly the opposite. More enrolled for Aadhar.

By 2015, over 900 million individuals had obtained digital identities via Aadhaar.

This marked a significant milestone, as it demonstrated widespread trust in India's digital infrastructure, positioning it for future success.

A revolutionary digital identity was born, setting the foundation for a new infrastructure.

Flirting with Cashless

India's payment ecosystem was already robust with systems like IMPS, NEFT, and RTGS.

Despite the strength, it was not commonly used for everyday transactions due to the cumbersome process of adding beneficiaries.

The average transaction sizes, INR 8,000 for IMPS, INR 70,000 for NEFT, and INR 9 lakh for RTGS, highlighted their use for larger transactions rather than daily commerce. Despite IMPS offering real-time transactions, its usage remained limited for smaller, more frequent transactions.

Between 2015 and 2017, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) made strategic decisions that significantly advanced India's digital payments landscape to increase financial inclusion and push for a cashless economy.

It began by issuing licenses to fintech companies to operate digital wallets, with Paytm emerging as a front-runner. However, the limitation was that these wallets required pre-loading of funds. A good solution but still sub-optimal.

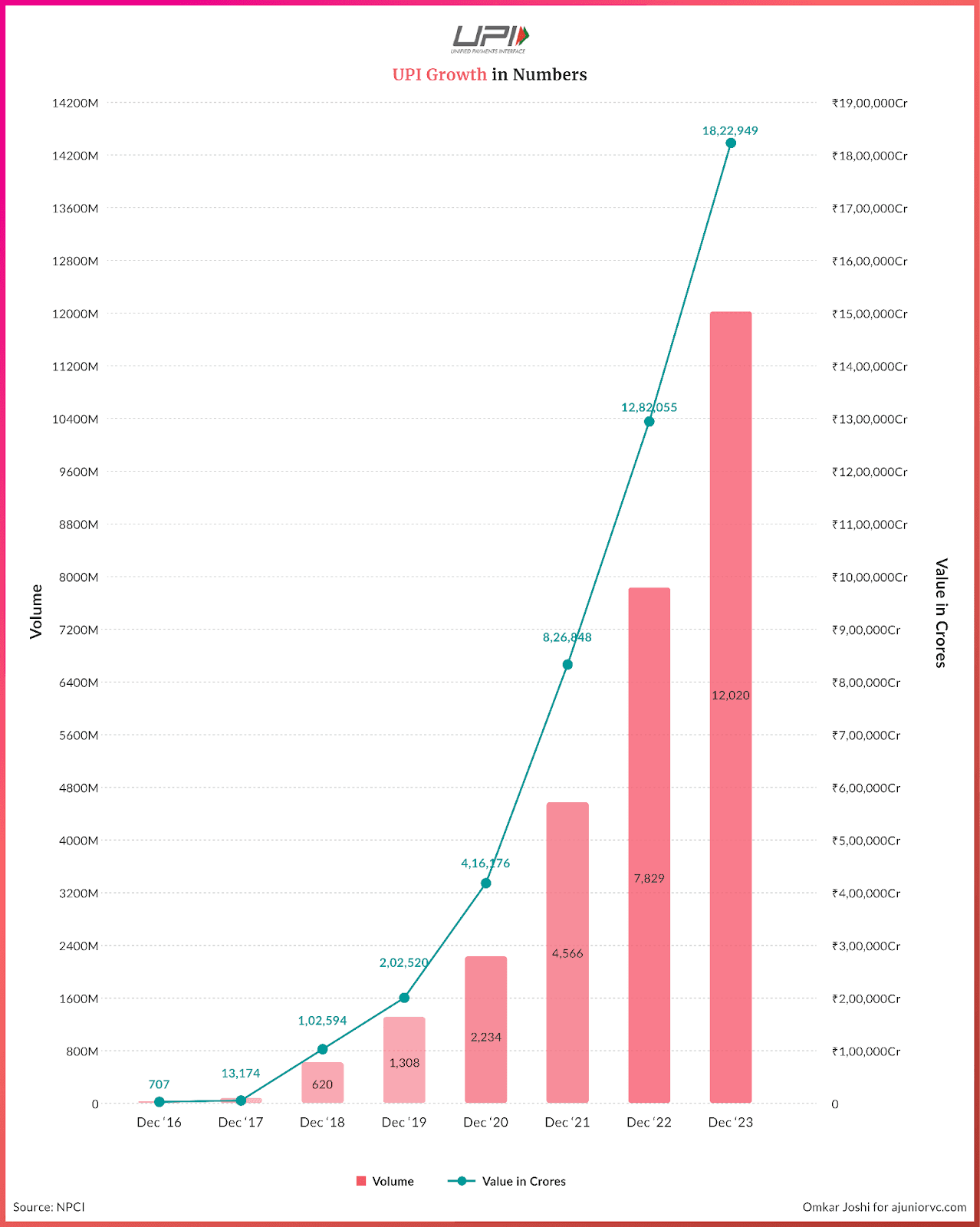

In 2016, Regulatory authorities innovated by integrating a new component into the retail payment ecosystem, the Unified Payments Interface (UPI).

This innovation enabled banks to interact and exchange payment instructions with non-banking entities in real-time, positioning UPI as a crucial layer of the India Stack.

UPI’s key feature was interoperability, allowing transactions across the financial spectrum, regardless of the institution's size or sector. This level of accessibility encouraged even startups to engage provided they partnered with a bank or acquired a special license.

This ensured that all players remained under regulatory scrutiny to promote financial inclusion and stability.

With the new system, street vendors and small traders without a bank account could receive payments for goods or services through a digital wallet. They could instantly transfer funds to someone else, such as a struggling relative in a remote village, so long as the recipient had a digital wallet.

The same year, Jio's entry into the market disrupted telecommunications, making data affordable and accessible to millions.

This had a cascading effect, empowering the average Indian with internet connectivity essential for digital payments to take root.

The demonetisation move in 2016 accelerated the adoption of digital payments, and by 2017, transactions via UPI neared the volume seen with IMPS, crossing the Rs. 50,000 crore mark.

People adopted the new in just a year.

India Stack's launch was the spark that lit the fintech fireworks, with regulators fanning the flames. India was all set to surf the giant wave of digital payments.

One QR Code to Rule

By July 2018, the NPCI reported a staggering 236M transactions in total.

PhonePe would become the fastest Indian digital payments company to cross the 100M mark and would boast a market share of 40%.

UPI was slowly becoming mainstream. But much of the credit belonged to Paytm, who had been steadily setting up the infrastructure since demonetisation hit the country.

Over two years, Paytm partnered with over 14M merchants and expanded its reach to over 2M retail outlets.

All this is done through their “scan any QR code to pay using Paytm” campaign, which is focused purely on the flexibility and ease of payments.

The QR or Quick Response code was pioneered by Paytm, who hired over 10,000 agents to promote and expand their network, aiming to make “Paytm Karo” the slogan for all payments.

People across the country, from auto rickshaw drivers and Kirana store owners to fast food joints and top-end restaurants, adopted the Paytm QR.

PhonePe and Google Pay (or Tez) would quickly follow suit, using the Paytm playbook to ship their QR codes to merchants and outlets.

The QR code would become the standard method for any UPI payment. Scan the code, enter the amount, and tap pay to complete the payment.

Each player, though, was pushing for a closed ecosystem as a means to gain loyal customers. This meant that users could only make payments to users on the same app,

The RBI felt otherwise and came out with a masterstroke in the form of the interoperability mandate.

The mandate allowed customers to make and accept payments from users of different payment apps. Users did not have to choose one app or any particular provider to send money to friends, store owners or to pay their bills.

This would set the UPI to become a national payment system.

As the fight for supremacy in the UPI space continued, 3 founders saw what no one else saw—the hassle of maintaining multiple QR codes for merchants whose customers each had their preferred platform.

Enter BharatPe.

The idea was as simple as it could be. A standardised, interoperable QR code containing all the merchant’s information is encoded.

Multiple UPI apps could be condensed into a single sticker, and the payment system would be simplified ten-fold.

The numbers spoke for themselves, as the BharatPe QR codes would be adopted by over 1M merchants in less than a year.

With payments as seamless as possible, October 2019 saw UPI cross 1B transactions and over 100M users in a mere 3 years after its launch. Over half of all digital payments made in India came via UPI.

This also led to the creation of an interesting market of small P2P (Person-to-person) transactions.

The ease of sending money to friends and family and the numerous cashback, referral and discounts offered on P2P transactions saw this segment account for over 90% in 2018.

This would change by 2019, as the commerce adoption on UPI would explode. It would also set the stage for a new commerce network.

The P2M (Person to Merchant) segment would grow to 34% of all UPI transactions, on the tails of all the impressive work done by the payment providers in India.

The success of UPI would not go unnoticed, as neighbours Singapore and UAE, both lush with Indian expatriate populations, began exploring the international feasibility of UPI.

Google, having seen immense success on their Google Pay platform thanks to UPI - onboarding 67M monthly active users, would recommend India’s UPI system to the US Federal Reserve as a model to follow for real-time payments.

India was genuinely harnessing local innovation to replicate for the world. But a century event was about to unfold, truly testing the efficacy of the India Stack system.

Nobody knew if it was it ready to deliver or crumble in the madness.

Starting Phase 2.0

When the pandemic hit and the world stopped - millions were left without any support.

At that point, the Aadhar-based Direct Bank Transfer was rescued. An incredible $24B were distributed to 800M people DBT was built for scale, and COVID proved that it could be relied on to deliver in times of crisis

DBT was triggered by the expensive way of delivering these schemes. 20 years ago, India spent INR 3.65 in delivery to provide one rupee of development.

DBT delivered these cash benefits much more efficiently, thanks to the JAM trinity - a Jan Dhan bank account, Aadhaar as the verification tool, and mobile phone as the personal operating system.

It was time to elevate the digital experience to the next level.

On India’s road to building the Digital Public Infrastructure, it was time for Phase 2, starting with Account Aggregation.

Phase 1 gave everyone a digital identity with Aadhar and electronic transactions via UPI. Phase 2 would harness the power of decentralised financial data, enable commerce, credit and investments.

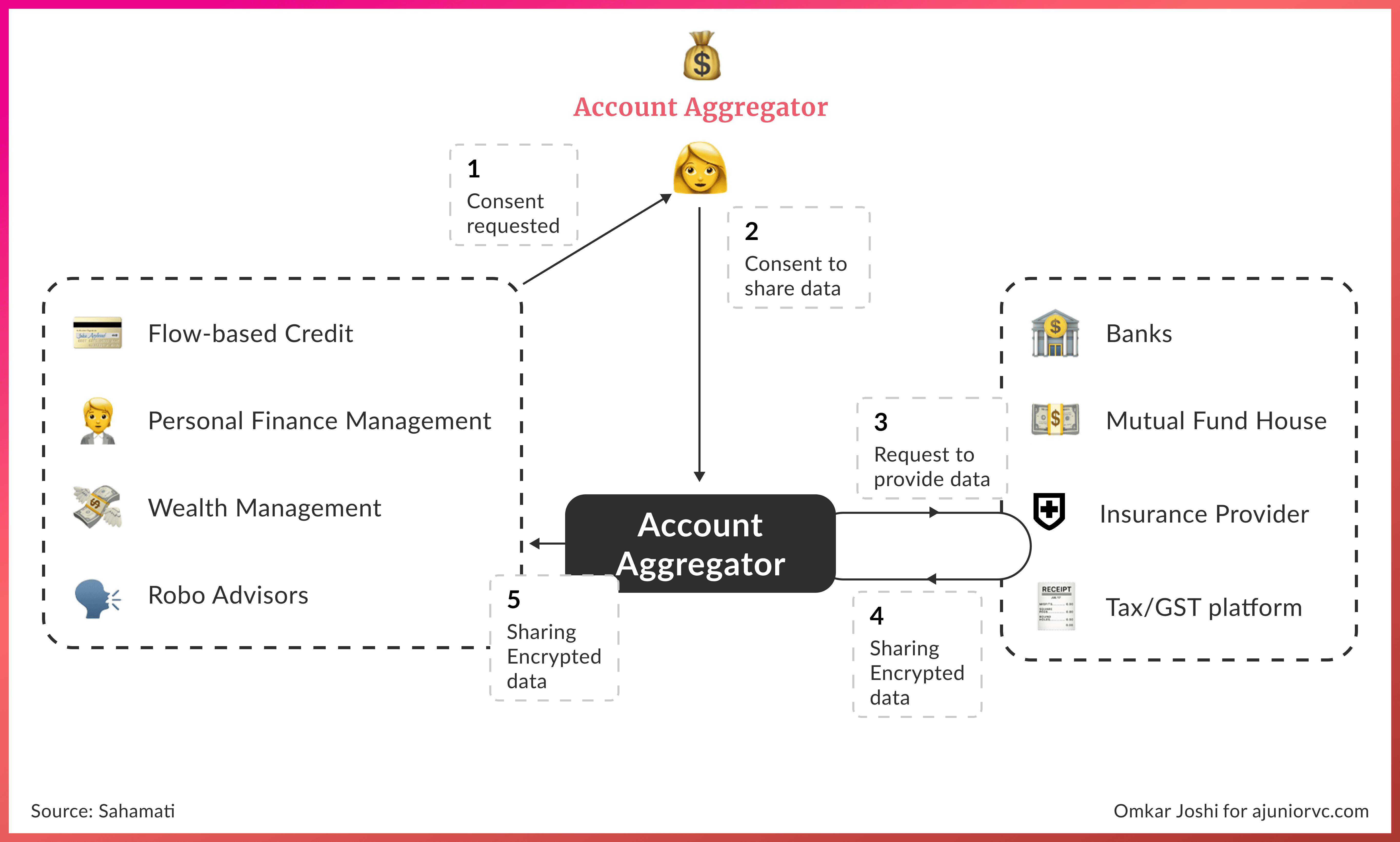

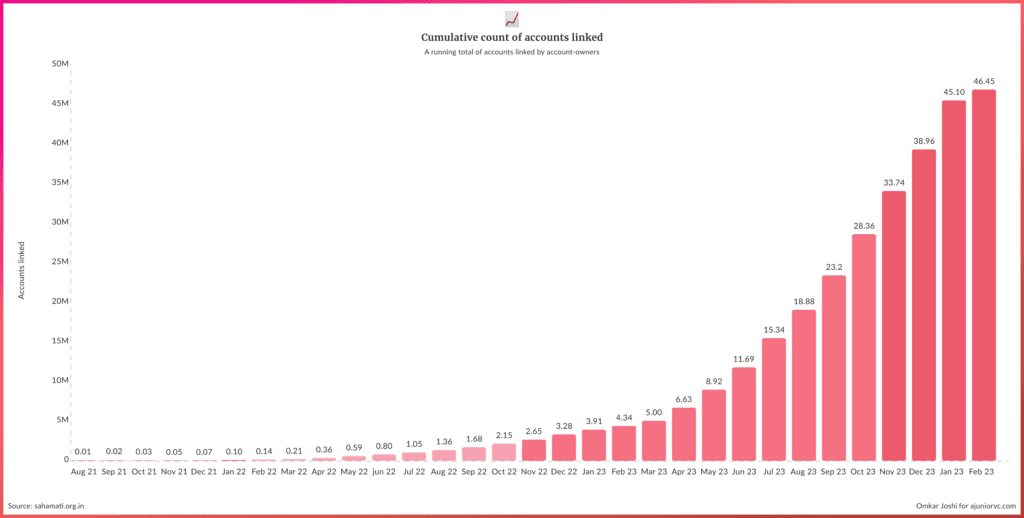

First conceptualised 5 years before the pandemic. Account Aggregators had a simple function. AA’s had to securely and efficiently transfer financial data from where it is stored to another place where it is needed, with explicit user consent.

Imagine you are applying for a personal loan, manually uploading all your financial proof documents to the lender’s website. Instead, you consent to the lending platform to fetch all your financial data from recognised AAs that can be shared in a single click.

They worked with 5 steps across 6 entities.

The opportunities seem immense, just for lending, 4% of credit loss comes from doctored financial documents - AA solves this with a transparent flow of data, The cost of processing a loan application via AA has been reduced to INR 100 from INR 440, offering significant cost efficiencies to lenders.

The use case lies in something other than lending, such as income verification, wealth management, and insurance.

The utility of AA was to imagine a future where your income verification can be done by your dating/matrimony app - to create a more trustworthy solution. Although only a data provider can be a data user, Sahamati planned to roll it out for everyone in the future.

Account Aggregator system was imagined to be a standardised, private and fully user-controlled consensual sharing platform, and the ecosystem is fast evolving with over 22 financial instruments connected, including current accounts, equities and PPF.

Aadhar databased personal essentials for a billion-plus Indians. GSTN managed the same with business information. AAs could now house financial information and enable individual users to validate who had access to it.

As the world struggled, India was determined to digitise its way to progress.

Wide OCEN

At India’s population scale, too much of a good thing is great.

The blazing success of UPI begot more success. iSPIRT, the Bengaluru think-tank behind UPI, AA and the larger India Stack, including e-KYC and DigiLocker, was not one to rest on its laurels.

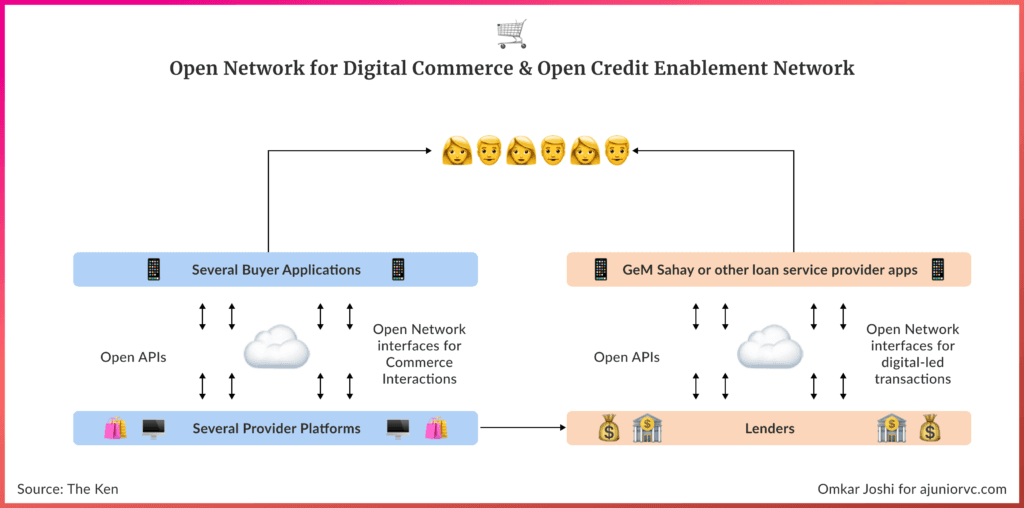

It launched the Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN) in mid 2020 to create a ‘UPI for credit’ for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). MSMEs in the country were typically cash-strapped as they would buy with cash and sell on credit.

They were deprived of access to formal credit as risk-averse banks shied away from lending, resulting in a credit gap estimated at $300B or INR 25 lakh cr. OCEN intended to bridge this through digital lending.

It collaborated with Government E-Marketplace (GeM), the platform for procuring goods and services for government departments and organisations, to launch the Sahay app in 2021.

The app put in APIs to facilitate collateral-free loans to MSMEs based on their unpaid invoices. The credit-protocol framework was designed to democratise access to credit by replacing the need for asset collateral with reliable business data and informed decision-making by lenders.

OCEN boldly chose to be borrower-first in its construct. Lenders on the platform could price their loans based on borrower information. Borrowers then had the discretion to select the best offer.

Lenders could achieve sizable savings in costs associated with distribution, customer acquisition, loan processing and collection. Likewise, they did not have to maintain customer-facing infrastructure after the initial integration.

The platform had a set of loan service providers to streamline the demand. Lenders could focus purely on underwriting, turning credit into a mere commodity.

For all these promises to come true and for OCEN to bring about a payments-like revolution to credit, it had to assemble an array of market participants onto a single network.

As UPI showed, nothing succeeded like network effects.

OCEN had its task cut out, given the complexities of an interlinked origination-to-repayment cycle of a credit relationship compared to the autonomous nature of a solo payment transaction. A credit product naturally called for more trust-building and checks against adverse selection.

The building blocks of previous digital payment systems also supported UPI. On the other hand, OCEN was the first attempt at creating an interoperable digital lending infrastructure. Besides, its B2B utility naturally translated into less visibility and potentially slower user adoption.

OCEN would prove to be one of many repeat acts.

Creating Commerce

By 2021, India had a proven model.

India could execute collaborative innovation, seamless integration, and cohesive implementation by the government and private firms to create scalable digital public goods for daily use.

The time was ripe to replicate the playbook and enable technology for commerce.

In December of that year, the government’s Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade set up a non-profit organisation named Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC).

ONDC intended to promote an open network based on an open source methodology, using open specifications and network protocols independent of any specific platform. It could digitise the entire value chain, standardise operations, promote inclusion of small suppliers and drive efficiencies in logistics.

A horses-for-courses approach to commerce, across food & beverage, grocery, electronics, fashion, beauty & personal care, was to drive tangible value for all parties involved, including the end user.

ONDC was launched in September 2022, with confirmed investment worth INR 250+ cr. from more than 20 domestic heavyweights. Unlike iSPIRT, which took a volunteer-based approach to OCEN, ONDC owned the data and could regulate the ecosystem, much like NPCI for UPI.

In parallel, the pandemic and its unique challenges presented India Stack with its final frontier – welfare at the population scale, beyond just direct benefit transfers.

The promised land for a welfare state was that its measures be pervasive, that the benefits be ubiquitous, and that state’s overall role be transformational. It was time for the rails of India’s Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) to be used to serve the public itself.

As consecutive lockdowns upended lives and young children were confined to online classes, 5.3M learning sessions were enabled by 12B QR codes of textbooks under the Digital Infrastructure for Knowledge Sharing (DIKSHA).

Even as the pandemic abated, DPI’s ideology could be seen in AI applications such as Assisted Language Learning (ALL), piloted in 500 schools for over 45K hours. Teachers were also beneficiaries of DPI’s prowess under Project Saral, which digitised handwritten notes of 17M students across 130K schools.

Beyond schooling, the Ayushman Bharat Health Account (ABHA) or Health ID was floated as an initiative under the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) for Indian citizens to establish a centralised database of all their health-related data.

In perhaps the most ambitious exercise at institutionalising community knowledge, Kisan eMitra was piloted to store and share farming insights with more than 10 lakh users.

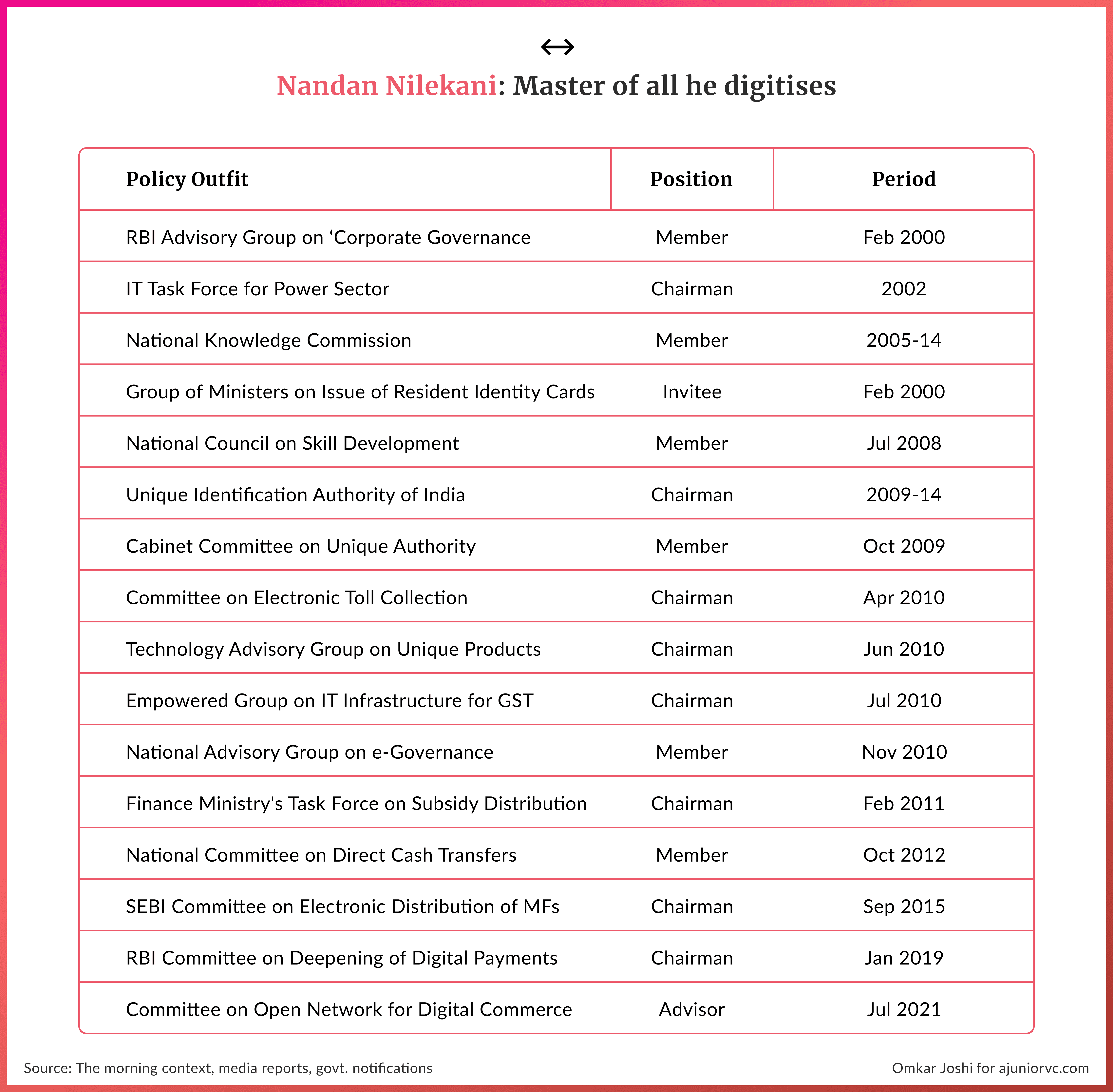

It was only fitting that DPI’s architecture and ambition were heavily shaped by India’s unofficial CTO, Nandan Nilekani, who was as much a philanthropist as a tech whiz and policy expert.

As India entered the end of the pandemic, India’s Stack had evolved to much beyond UPI and Aadhar.

It was beginning to permeate commerce and credit.

False Starts

By late 2022, the Government was leading innovation, access and ease of business from the front.

The Central Bank took a leaf out of the former’s book by allowing RuPay credit cards linked to UPI accounts.

In April 2023, it introduced a direct, collateral-free, pre-sanctioned credit line on UPI to make formal credit convenient, real-time, affordable and ubiquitous. Four months later, ONDC added financial services to its offerings, laying the foundation for an alternative to OCEN, which had scaled up to loans worth INR 21 cr, by then.

ONDC and OCEN had similar end goals but technicalities and use cases differed. For example, both networks adopted cash flow financing – through a buyer app on ONDC and a loan service provider on OCEN.

A layman's view suggested that ONDC could solve the problem faster and more holistically, This was given its potential to attract more players and diverse utilities within just financial services, such as insurance and mutual fund offerings.

On the other hand, OCEN could be held back by its reliance on the GeM platform, which had only 45K MSMEs on board. However, a mature view can foresee the likelihood of each spurring the other to strengthen the value chain, unbundle products and manage risks.

India’s 64M MSMEs could do with more than one public lending platform.

It was difficult to fathom but even UPI took a couple of years to show early signs of turning into the beast it was destined to become. Announced in February 2015 and launched in August 2016, it was only in 2017 that there was a noticeable uptick for the first time.

ONDC and OCEN would possibly go through their respective cycles. While ONDC started with hype, it struggled to live upto it. A 3 sided marketplace with customer, vendor and provider was hard to balance, along with high costs.

Given UPI’s precedent, people naturally expected any similar concept to take off quickly. However, the reality was that the population scale could not be hacked or engineered.

Critically, as the world absorbed the disruption caused by ChatGPT, India’s DPI served as a good example of what generative artificial intelligence should aspire to be. Use-case driven, outside-in rather than inside-out, razor-focused on making people’s lives better than blindly pursuing razzmatazz technology for the sake of it.

Beyond the end utility, DPI’s technical architecture principles of interoperability, minimalist technology, reusable building blocks and broad-based, inclusive innovation also offered a template for governments and corporations worldwide.

As India entered 2023, the ambitions of DPI were no longer limited to India’s borders.

Investing Stack

2023 was a ripe time in India.

The G20 Presidency was an opportunity to push the agenda of all the good work done earlier and for future products.

As India showcased itself in February, UPI was enabled in UAE, Singapore, Mauritius, Nepal, and Bhutan. The headline act had set the stage for even more innovation.

As the idea of DPI spread to more categories, it looked at making investing easier. It would own Mutual Fund Central, enabling retail investors to own and control their data.

India’s capital markets were booming due to the mass transition from physical and other asset classes like fixed deposits and gold to mutual funds.

Along with the transition, all asset classes grew, new capital was infused into the capital markets, and SEBI set the regulations of the assets.

With 50 lakh crores in Assets under management for mutual funds, India had witnessed a sixfold increase over the last 10 years. The institutions in charge were AMFI, RTA, and the regulators, pushing the agenda.

Two private for-profit institutions, Kfintech and Computer Age Management Systems, collaborating meant DPI India's agenda was purposeful for the end customer and financial institutions.

With more NRIs looking back at India to Invest, the time is ripe to take off.

The UPI wave was the ability for other regulated institutions to come together and solve the agenda for interoperability when all the banking institutions came together.

With investments picking up, other asset classes will also offer combined solutions that may make it seamless for any actions credit and investment solutions provided to investors.

Depositaries like CDSL may also have to build an architecture to make it seamless for the financial assets to come under a similar umbrella architecture.

With real estate being fragmented, the ability to digitise it may well propel India to be one of the top digitised nations on the Digital Public infrastructure.

This data, in turn, would be used to build Digital Public Intelligence for consumers to transact with their assets and liabilities and fuse with commerce and trade across countries.

Powering all this would be the germ of the idea that was becoming a formidable force.

Like UPI’s slow start followed by exponential growth, the account aggregator ecosystem had begun to take off. By the end of 2023, almost 46M accounts had been linked with AA.

The ecosystem developed into over 500 entities in various stages of the onboarding process. India’s DPI was not limited to UPI as its one trick pony.

An idea that started almost 15 years ago was now taking shape as a global leader.

DPI from India to the World

When the Internet was invented, it was formed by the US Defence’s Advanced Research Projects Agency Network.

This public organisation was run like a private organisation back in 1969. The DPIs — identity, payments, and data governance layers that pioneered the network effects- are run by the National Payments Corporation Of India (NPCI).

It drives Open Finance with Account Aggregator, which started the AA framework. Now, AAs are regulated by RBI to protect privacy and data. It includes inclusive commerce with Open Network Digital commerce and more.

India’s strength to build IT services, software for all, good governance, and inclusivity ideology had taken a front seat.

Swift, Visa, and Mastercard have succeeded due to the ability to be decentralised across all countries in a highly secured and privacy-first approach.

Countries that governed the ability to settle and transfer funds had provided better to the world and became global leaders.

In India, UPI has shown us how to export to over 10 countries; now, it’s the opportunity for the other part of the DPI – identity, data governance, and intelligence.

The next opportunity lies in building data stacks. Countries like Singapore have already been using it with SGFinDex. An architecture similar to the Indian Account aggregator system will ensure that data across countries and continents can be passed with customer consent.

Amongst all countries, developing and developed, India is probably the farthest ahead in digital public infrastructure. It is no wonder that countries worldwide want to adopt India’s solutions.

India’s bigger opportunity thus potentially lies with DPI as a packaged Solution” (DaaS).

This could be an approach India will provide the whole DPI stack for countries to use as a software service with controlled privacy with the country's own localised mechanisms and governance structures.

The Internet took off due to secularity, affordability, and interoperability across all geographies; India’s opportunity to provide to the world lies here.

Like China is building the Belt and Road initiative and the physical Infrastructure, India will continue to build the world’s digital public infrastructure.

India’s first big push started with the Aadhar in 2009 and ended with the launch of UPI in 2017. India Stack 2.0 has been built on this formidable foundation, with AA, OCEN, ONDC and MF Central. As we have seen over the last 6 years, the open stack provides an incredible unlock to economic activity.

India Stack’s 2.0 could take India’s $100Bn fintech ecosystem truly global

Writing: Keshav, Nikhil, Raghav, Parth, Shreyans, Tanish and Aviral Design: Omkar and Chandra