Oct 15, 2023

Is $1Tn Lending the Ultimate Goldmine for Fintech?

Lending

Finance

Aggregator

B2C

B2B

Series H+

Last fortnight reported an explosion in consumer loans, hot on the heels of the massive Global Fintech Fest where $2Bn worth of deals were signed

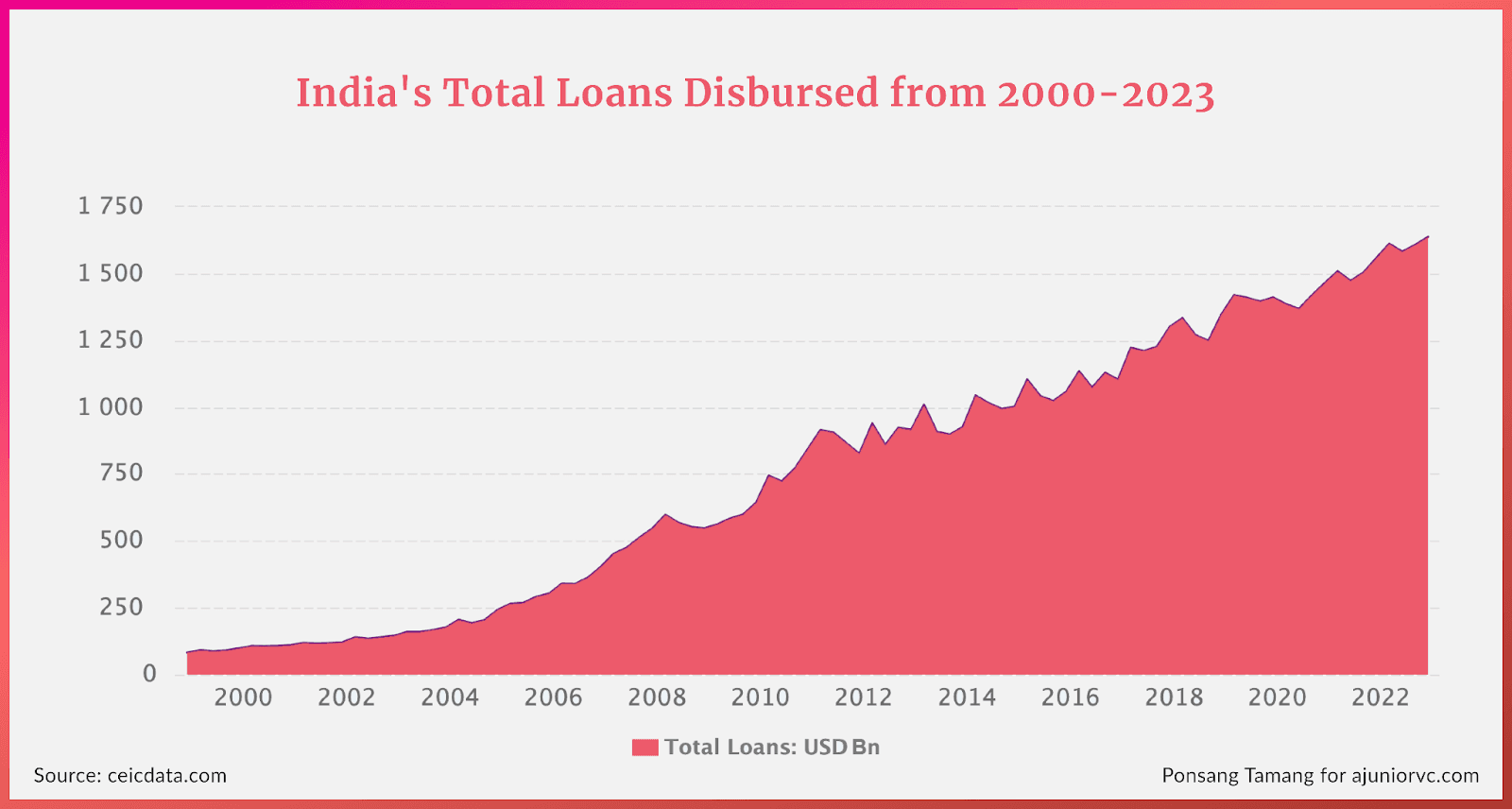

Putting Loans on The Scoreboard

The origins of lending in India trace back to the 5th century B.C when loans were extended in cash and kind.

Over the past many centuries, financial transactions evolved from simple barter systems to complex digital ecosystems. As systems evolved, lending became a timeless catalyst for progress and stood for economic growth and empowerment.

As civilisations expanded and economies became more complex, lending institutions gained prominence.

The first Indian texts talked about usury or the practice of charging unreasonably high interest or making immoral monetary loans.

Eventually, lending became acceptable, and ancient texts such as the Manumriti recognised it as a way to acquire wealth.

Early mentions of a systemised lending structure trace back to the Maurayan age around 321 BCE. Kautilya’s texts during this time also mention different forms of loan deeds - the lender’s legal right to the borrower’s property should the borrower default on their loan.

The Mauryan period also had an instrument called adesha, akin to the modern bill of exchange, that directed a banker to pay the sum on a note to a third person. Merchants also gave letters of credit to one another.

Ancient Sanskrit texts on law and conduct, or the Dharmashastras, speak about extending business loans. However, these only permitted the Vaisya caste, mainly merchants and farmers, to become money lenders.

Class structures determined who had access to capital and who they could lend it to.

Loan deeds continued under the Mughal era and were popularly known as Dastawez. These got further classified into loans ‘payable on demand’ or ‘payable after a defined period.’

In Medieval India, from the 12th century AD, a financial instrument called Hundi was developed for use in trade and credit transactions - a couple of centuries before bankers in Western Europe issued bills of exchange.

Hundis were used to transfer money from one place to another, as a bill of exchange in trade transactions or as a credit instrument to borrow money.

As commerce picked up in society and people began to trade with each other, the growth of credit followed.

While people called it different names, the underlying principle of lending a sum of money and earning interest was beginning to grow in relevance.

Banking Opens Credit for Independence

The Industrial Revolution introduced manufacturing and industrial processes to the world.

This expanded the lending systems to serve the increasing demand for capital required to fund industries.

In the 1700s, entrepreneurs in India received loans from merchants and aristocrats and used the money to expand their workforce, buy machinery or build inventory. ‘Seths’ and ‘Shroffs’ extended small business loans and enabled merchants to fund their trade.

However, this came at rates well above the formal channels and often at unfavourable terms. Another common practice was ‘indentured loans’ where borrowers would repay the debt by working on the lender’s estate.

While India had developed credit instruments and money lending systems, the British brought a structured and anglicised form of lending and banking.

The western type of joint stock banking - banks owned and controlled by shareholders - was brought to India by the English Agency house of Calcutta and Bombay.

In 1770, the Bank of Hindoostan started operations in Calcutta to provide business loans for foreign trade. Some banks like the Bank of Calcutta in 1806, were established to fund wars against the Marathas and Tipu Sultan.

The Allahabad bank, still functioning today, was set up in 1865. The first entirely Indian joint stock bank was the Oudh Commercial Bank, followed by Punjab National Bank in 1894.

With the establishment of these banks, the 20th century in India saw relative financial stability. Several smaller banks, for example, the Catholic Syrian bank, also cropped up to serve particular ethnic and religious communities.

Two broad sets of institutions emerged - exchange banks, owned by Europeans and focused on funding foreign trade, and Indian joint stock banks that catered to local businesses. The latter were undercapitalised and needed more seasoned to compete with the exchange banks.

Many collapsed in the 1900s.

Inspired by the Swadeshi movement, many Indian banks sprung up post 1906 and have survived until today. Some prominent names include Bank of Baroda, Corporation Bank and Bank of India. The movement's zeal spread to the South's Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts and saw the emergence of many private and national banks, including Canara Bank.

In 1935, the Reserve Bank of India was established with a paid-up capital of fifty million rupees to support the economy post the economic challenges of the First World War. It sought to supervise financial institutions, control the currency and manage government credit.

The banking institutions of pre-independence India laid early foundations of lending that would help move the wheels of the economy post-independence.

Lending as we know it today, was beginning to take shape.

Credit Hits the Economy Out of the Park

Significant milestones mark the evolution of India’s banking system, the most pivotal being the 1969 nationalisation of banks.

This move democratised credit, transforming a predominantly urban-centric landscape—where 83% of 14,000 bank branches were in cities—into a more inclusive one, with total branches reaching 58,000 by 1980 and 40% in rural areas.

Such changes propelled sectors like agriculture, with its credit share jumping from 2% in 1969 to over 13% by the late 1970s.

Nationalisation increased India's GDP from 3-4% in the late 1960s to 5% in the following decade. Around this period, in 1961, Kali Mody introduced the Diners Club Credit Card, anticipating India's transition to digital banking and cashless transactions.

However, credit cards became mainstream only in the 1990s.

The 90s started with the economic earth-shifting 1991 economic liberalisation. The unlocking of India aimed at reducing trade barriers and state intervention.

This move increased foreign direct investments from $132 million annually from 1985-1991 to $5.3 billion between 1992 and 2000. Concurrently, the credit growth rate increased from 15% to 18%, and GDP growth averaged 6.7% between 1992-1997.

Along with nationalisation and liberalisation, the genesis of ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank, and IndusInd marked crucial moments in India's financial sector.

The Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India (ICICI), had been founded in 1955. The credit corporation was structured as a pioneering joint venture encompassing the World Bank, India's public-sector banks, and insurance companies to deliver project financing to the burgeoning Indian industry.

Identifying the gap in specialized housing finance, HDFC, or Housing Development Finance Corporation, was conceived in 1977 as India's maiden specialized mortgage company.

In 1994, recognizing the potential to expand its footprint, ICICI transformed its legacy by inaugurating ICICI Bank as its wholly-owned subsidiary. The success and need for inclusive banking paved the way for HDFC Bank's incorporation.

By the 1990s, the credit card industry in India burgeoned, growing 35-40% annually with a volume of over Rs 2,000 crore.

As technology became a thing, the banks were the first to adopt them.

With Internet, banking transactions, once languorous, became as swift as trading shares in a bull market. Automation reduced the 'loanly' wait times for borrowers and brought banking to their fingertips, anytime and anywhere.

ECS, or Electronic Clearing Service, was one of the early entrants, debuting in the 1990s. This system automated bulk money transfers, like salary disbursements or dividend distributions, and gave a new meaning to "money at the speed of thought."

With ECS, the volume and speed of transactions experienced a significant uptick.

India's banking evolution post-independence was akin to a meticulously planned portfolio, balancing risk with innovation and tradition with technology.

The 2000s were going to become even more attractive for lending

Cautiously Running Credit Books

The early 2000s marked transformative periods for India's banking ecosystem.

The 2004 introduction of RTGS made high-value transactions real-time, eliminating tedious waits. It was akin to switching from a bicycle to a sports car on the financial expressway.

The subsequent launch of NEFT in 2005 catered to both large and small transfers, making funds movement faster and more efficient than ever.

While payment systems were upgraded to lightning, India's lending ecosystem would seem almost primitive by today's standards. Traditional banking practices reigned supreme, and credit penetration was relatively low.

In the early 2000s, India's credit relative to its GDP lagged behind some of its peers. For example, while China was robustly advancing its credit infrastructure, reaching a credit-to-GDP ratio of 90%, India was nascent, with its credit penetration only around 50% of GDP.

However, as with any great financial tale, India was one of promise and progress.

The first signs of change were the rise of Microfinance Institutions (MFIs). These institutions recognised that empowering women, especially through cooperatives, was the key to grassroots financial growth. By lending small amounts to women-led cooperatives, MFIs provided capital to those who needed it the most and instilled a credit culture in rural and semi-urban areas.

Democratization of credit was the result, where a lady in a remote village was as empowered to seek credit as her urban counterpart.

Microfinance Institutions (MFIs), which emerged strongly during this period, started lending amounts, sometimes as small as INR 5,000 ($70), to women-led cooperatives.

Yet, while the landscape was promising, it was challenging.

The rise of Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) in India was not without its share of turbulence. In 2010, the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, which accounted for nearly a third of the country's microfinance activity, witnessed a major MFI crisis.

Reports of aggressive recovery practices, over-lending, and multiple lending instances led to defaults.

The crisis was so severe that the state's microfinance portfolio at risk, a key measure of loan performance, soared to over 40% from a usual average of 2%. It was a classic case of too much money chasing too few genuine borrowers, leading to a dangerous bubble.

The MFI crisis 2010 wasn't just a blip on India's lending radar, but a lesson in the importance of sustainable and responsible financial growth.

It was time for a change. Enter fintech startups.

Filling the gap left by conventional institutions, these agile entities offered modern solutions in sync with India's evolving financial aspirations.

Early innovations like the banking correspondent (BC) model, pioneered by FinoPayTech and Eko India, brought financial services to the rural masses, minimising the reliance on traditional bank branches. Furthermore, by 2010, fintech ventures such as Oxigen, MobiKwik, Paytm, and Freecharge began shaping India's digital finance future, emphasising mobile payments and e-billing.

From the early 2000s to 2010, this era underscored India's transformative trajectory in finance.

The substantial progress during these years and the subsequent momentum hinted at India's potential to become a major global financial contender.

Loan Distribution is the Score, Collection Wins Games

As India entered 2015, it still was a capital-constrained country with a low per-capita GDP.

In addition, a large part of the population has very low income. This population segment is one unfortunate event away from drowning in debt. This made the opportunity for lending huge and diverse.

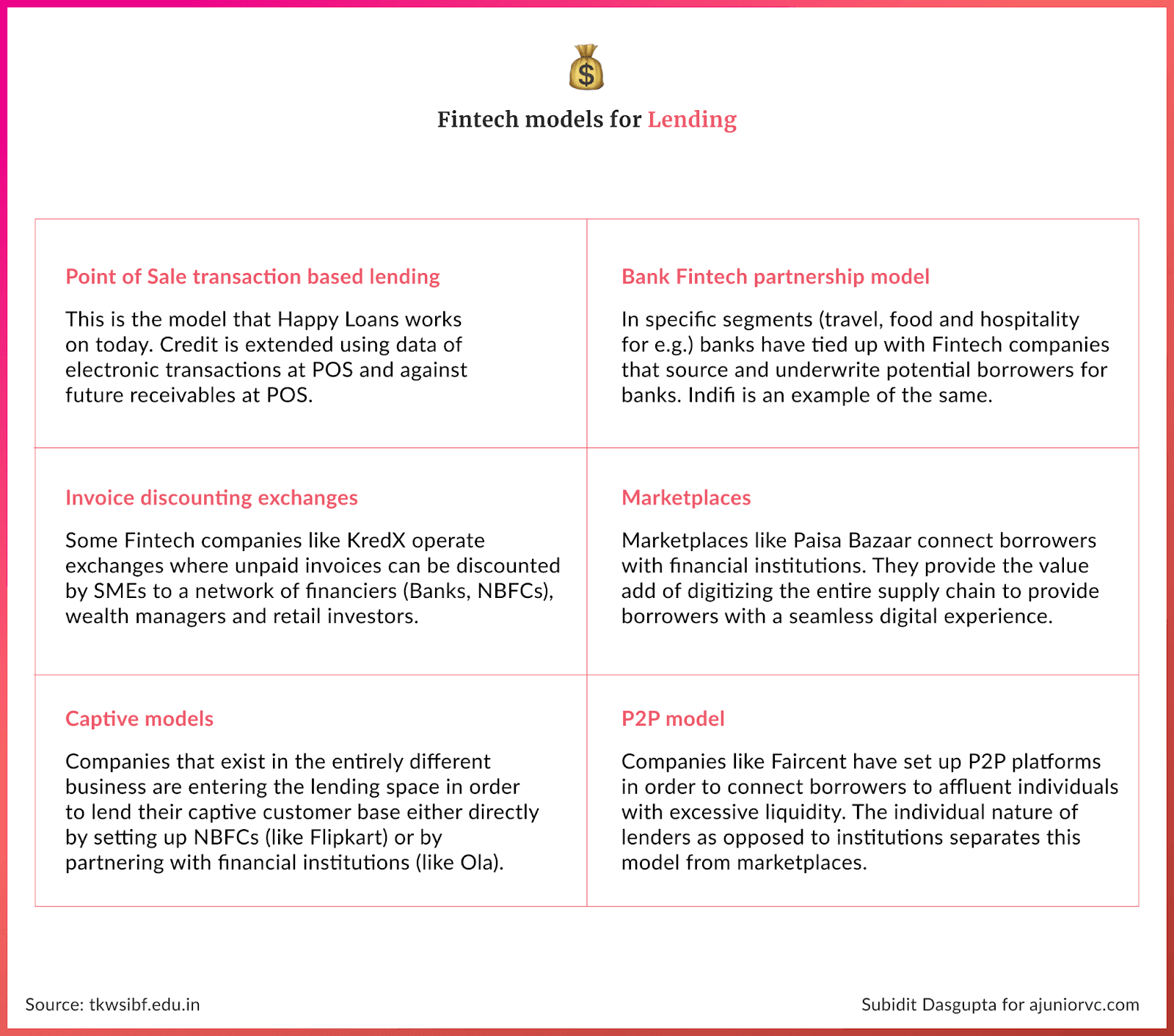

Fintech lending replaced asset collateral with information collateral.

This substitution was possible due to the Jio effect in 2016. With the digital revolution brought about by Reliance Jio, India saw an unparalleled surge in internet users. The vast unbanked and underbanked population now had a digital window to the world.

Reliance Jio’s introduction led to a spike in internet users, from 200 million in 2015 to 500 million by the end of 2018. This massive inclusion indirectly spurred digital financial services.

Between 2000 and 2018, the number of credit cards in circulation in India jumped from 6 million to over 24 million. Furthermore, the total transaction value of credit cards grew from INR 39,000 crore ($5.4 billion) in 2000 to an impressive INR 2.4 lakh crore ($35 billion) by 2015.

More importantly, the rise in digital transactions allowed businesses to have a digital footprint which could be shared with lenders as as proof of their repaying capacity. The introduction of GST in 2018 allowed lending companies to verify the GST invoices with the tax authorities.

These twin structural changes allowed companies to offer information collateral-based cashflow lending to businesses.

Lending could be very profitable, provided the collection system remains robust. As a business model, lending seems like an insanely profitable business, which it is.

Any startup in this space can easily make an NIM or the difference between their lending and deposit rates of around 4% on their invested capital. If they can increase the capital deployed in a year (higher demand), then their revenues increase without any other costs.

However, the key in this business is collections. It is very easy to lend, given that the latent demand in India is very high.

However, one shouldn’t look at just good demand but look at the collection system.

The strength of the lender is evaluated by its NPAs. For example, an NPA of less than 5% for unsecured lending is considered acceptable and good in the ecosystem. The key to maintaining a low NPA is having a great credit underwriting method.

Cash flow lending allowed a low-touch lending business model to take shape. Unlike Of-Business, which integrated business relationships with its lending product, this newer generation of cash flow lenders could work and lend profitably by working in a little more hands-off manner.

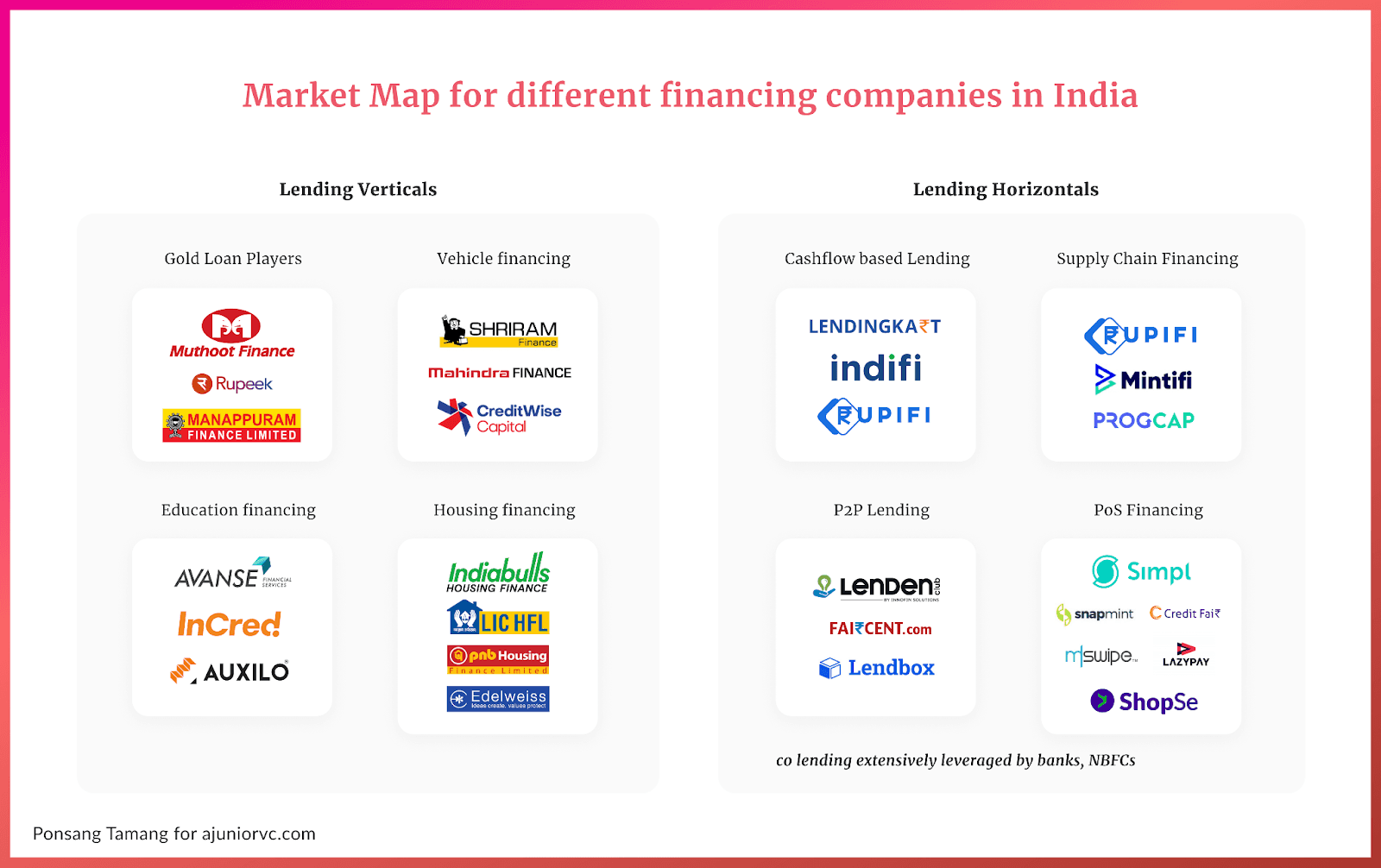

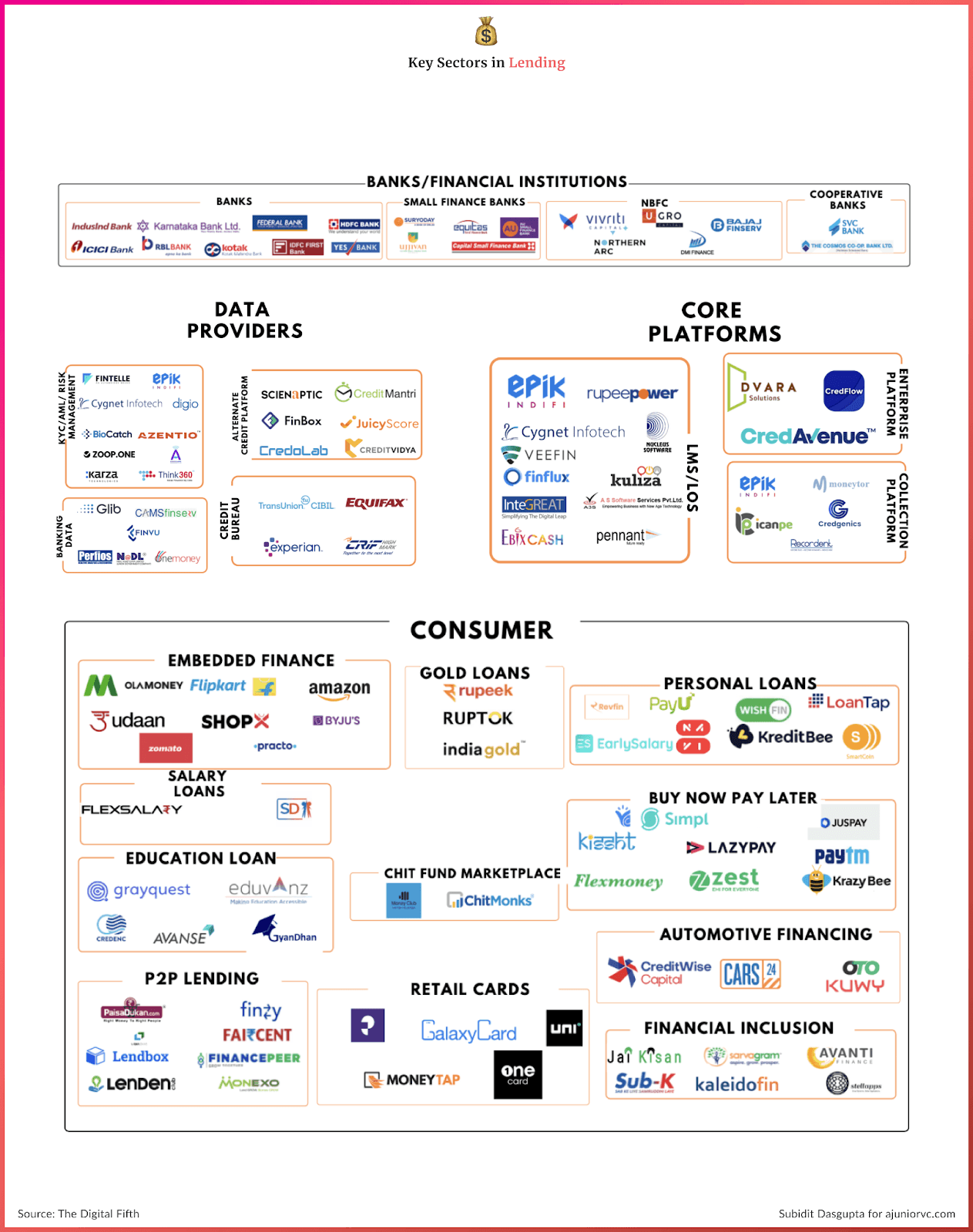

Due to these structural reforms, the market began to emerge in consumer and business lending.

On the consumer side, use case-based lending began to emerge. We have gold loan financing, vehicle financing, home loans and education.

This focus on narrow segments helps these firms improve their collection capabilities.

On the business lending side, there was an explosion in the kinds and types of lending institutions. The MSME lending opportunity in India is very large, while most had low collateral.

Interestingly, the approaches to business lending were mostly horizontal.

We saw early starters such as LendingKart, who offered invoice-based lending and then the arrival of similar companies such as Indifi and Aye Finance.

Supply chain financing was the other large emerging model.

Although the credit is being disbursed to the MSME, the quality of the underlying asset is the risk associated with the larger and well-established companies. Supply chain financing allows easier credit opportunities for MSMEs that supply to reputed businesses. Prominent supply chain lenders include Prograp, Mintifi, Rupifi and Viviriti Capital.

True to the diversity of India, lending models in India were also diverse to cater to different segments and needs

Fintech Opens Its Account

By 2018, the regulator's role became a key driver of the growth in the overall lending ecosystem, unlocking fintech.

The central bank introduced the co-origination framework in 2018, allowing banks and NBFCs to co-originate loans.

This model was designed to enhance the flow of credit to the priority sector, which includes sectors such as agriculture, micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), housing for economically weaker sections, education, and other sectors considered vital for the economic development of India.

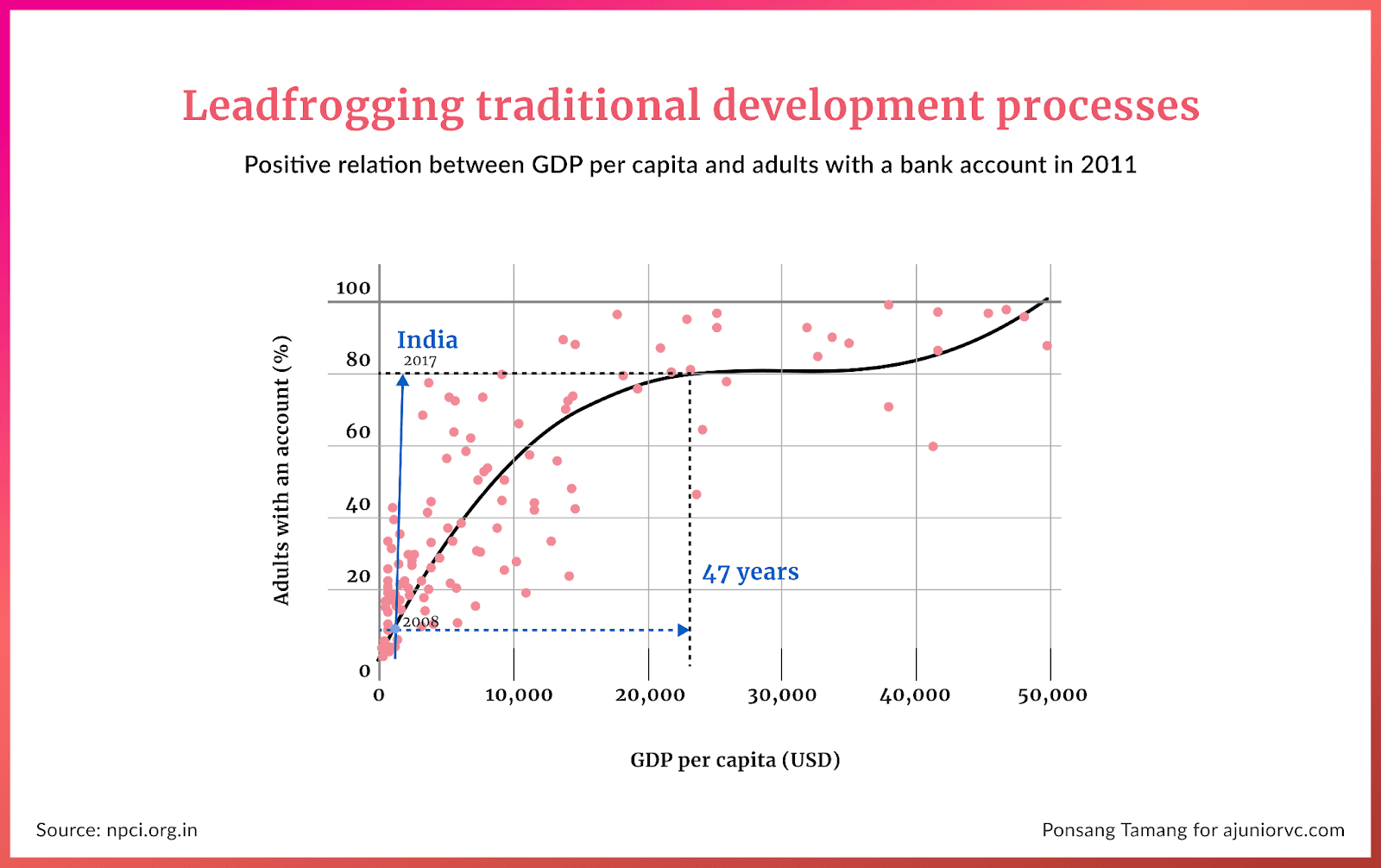

The framework allowed banks to take a share of the loan and a share of the risk associated with the loan. India had begun to leapfrog the traditional credit development path.

This regulation was subsequently upgraded to the co-lending model in 2020, allowing 80 % of the loan with the lender and 20 % minimum with the originator. This collaboration sowed the first partnership between NBFCs/fintechs and traditional banks to serve the market.

Co-origination/co-lending loans were originally designed to overcome the NBFC sector liquidity crisis brought about by the DHFL crisis.

Reeling under the impact of NPAs and the pending cleanup, the central bank looked to reduce the lending exposure of the financial system aggressively. In small-scale lending, the overall lending book shrank for a few quarters.

The co-origination and co-lending model opened up the growth in the credit space and underscored the importance of software to manage the lending book split across multiple organisations.

Several fintech infra SaaS players developed products which improved banks' LoS, LMS collection systems.

They made it faster, intuitive and up-to-date with the latest changes in the IndiaStack.

Firms like Lentra, Perfios, M2P, Zeta, Kiya.ai created LMS, LoS and even cloud-based Core banking systems to cater to the need of the new fintechs and NBFCs. This was a far different type of software as compared to the exisiting software products in the banking industry.

This new generation software allowed banks/NBFCs to cross-sell, and launch newer products quicker and faster. The system's building blocks were well established for an unexpected event and an even more unexpected outcome.

The COVID-19 shock and the hard lockdown meant that most of the country was left without a source of income and in dire need of funds. This meant that digital loans were the only source for anyone needing one.

Lending would be the saviour to revive the economy and give hope to millions to restart their businesses and livelihoods

Lending Explodes Off the Bat

The essence of an NBFC lies in the fact that they do not have banking license and that paradoxically gives them a unique edge.

NBFCs couldn’t receive demand deposits, meaning funds costs are significantly higher than traditional banks. Tech companies that could understand their users and iterate to build incredible products, could win.

Many would jump into the gold rush.

One such example was Slice. Founded in 2016, they were a B2B buy-now-pay-later service for the first few years. In May 2019, Rajan and the team pivoted to cards for consumers.

Growth was explosive. Slice partnered with the Bank of Mauritius India to offer loans through prepaid cards (PPIs). Working with merchants to cover the costs, they could offer 4 interest-free purchase instalments.

By doing so they could tap into India’s large, underserved credit market offering loans to people who were not eligible for a credit.

Tech companies were able to innovate on business models and come up with creative ways to underwrite their loans, often at the cost of operating in a regulatory ‘gray zone’.

As competition intensified and new business models like Slice’s gained mainstream popularity, more startups pivoted to retail lending.

Jupiter, Paytm, BharatPe, Cred and several other fintechs would see the popularity of the consumer lending/ BNPL model and quickly launch competing products.

FinTech startups could focus on niches to start but as they grew more of them had to foray into lending to generate sustainable meaningful revenue. Competition for lending was intense by the time Covid hit.

With people at home and the economy at a standstill due to Covid, the government had to act.

Banks' non- performing assets (NPAs) were already up almost 50% at 8.5%, and RBI expected NPAs to rise to 12.5% by 2022.

In March of 2020, amidst the pandemic, the RBI offered relief measures to borrowers in the form of EMI moratorium on all term loans. Later in the year, the RBI permitted a one-time restructuring of small business loans and a 50,000 Crore Covid shield for private banks.

As the country emerged from the pandemic, the government took a closer look at PPIs and the BNPL model.

In July 2022 a Central bank directive barring prepaid instruments from being loaded with credit would send many FinTech firms into a tizzy and bust their business models.

While fintechs wanted to grow wildly like the Wild Wild West, RBI wished to ensure the economy was not under undue stress. The regulator's goal was to ensure lending remained fair, collections remained non-predatory, and access to credit was not on a free flow tap that increased indebtedness in the economy.

The tension would keep bubbling with innovation.

Credit on UPI Finds the Gaps

Where one door closes, another must open with a QR Code.

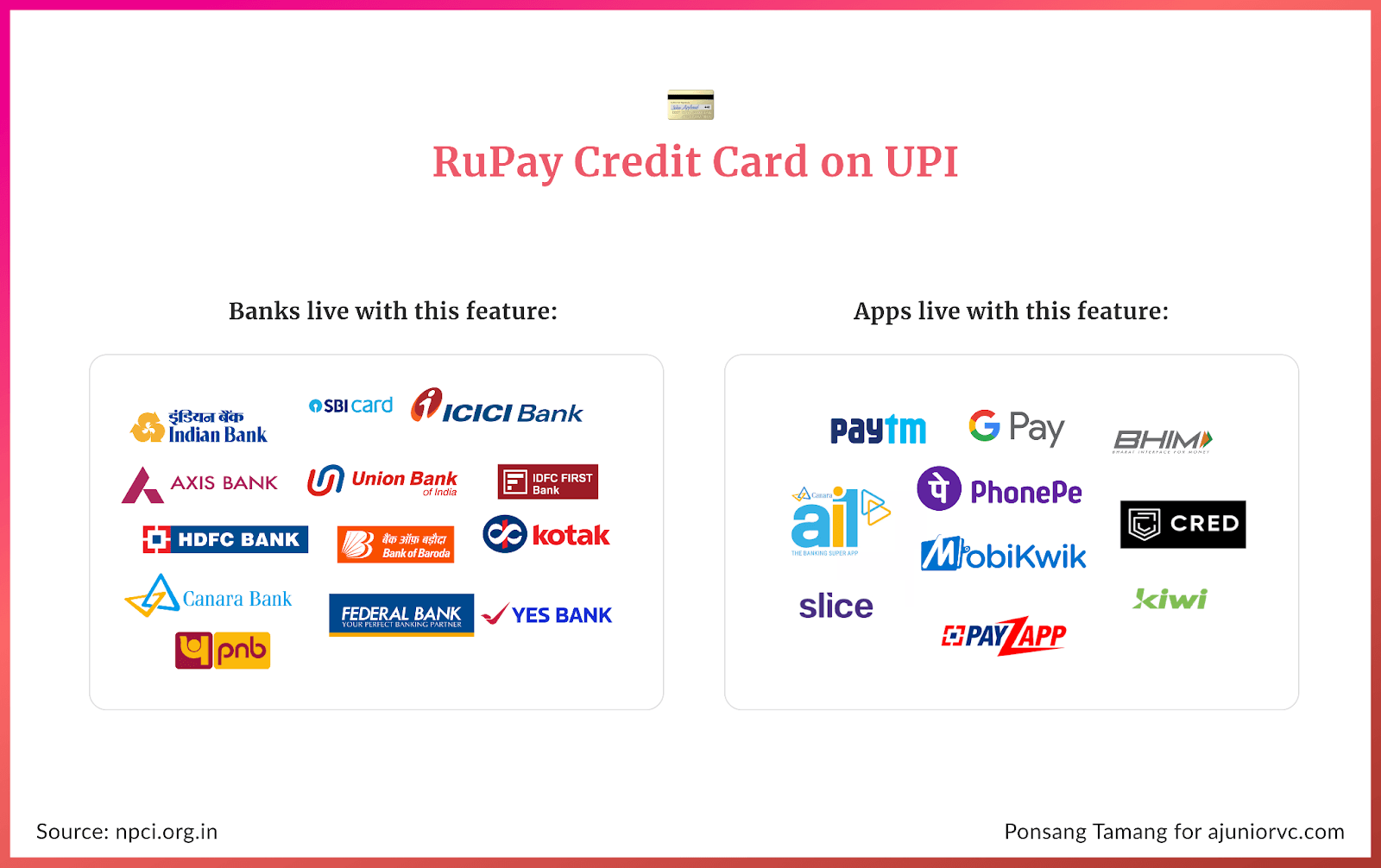

Formal credit in India aspired to be convenient, real-time, affordable, and above all, ubiquitous. UPI has been all of these and much more, to amass 300 million retail users and 500 million merchants in just seven years.

The interface was India’s proud export to France, Australia, Singapore, and the Middle East.

The mandarins at the RBI duly recognized the potential of adding formal credit on top of the platform, taking a leaf out of India Stack’s structure of interoperable layers.

The Central Bank began to operate in a one-two-punch model. It would be steadfast in accelerating innovation and ruthless in doing away with models that err on the wrong side.

In June 2022, it first allowed RuPay credit cards to linked to UPI accounts. By August, Slice, Uni and PayU’s Lazy pay had to stop onboarding new customers. Their card partner, the State Bank of Mauritius India awaited clarity on the regulator’s views on the model.

In April 2023, it took a decisive step, introducing a direct, collateral-free, pre-sanctioned credit line on UPI.

But then in June, it issued a directive to crack down on FinTech, severely impacting at least fifteen players. The message was loud and clear – innovate, but in the consumer’s best interests.

UPI’s distribution could act as wings for access to credit to take off. It is still early days for the union, with concerns around UPI ceasing to be accessible to accommodate a merchant discount rate. Will UPI on credit kill credit cards after giving a sucker punch to wallet system remains an open question.

But reckon this, it took 70 years for India to install 6 million POS machines. UPI was able to clock 60 million merchants in just over three years. The platform’s bid to boost the volume, velocity, and variety of credit appears redoubtable.

UPI’s digital footprint could eliminate knowledge asymmetry in the domestic credit space. Or as Nandan Nilekani puts it, replace asset collateral with information collateral, spurring the next generation of digital lenders, a wave of business partnerships and new business models.

Kiwi became the first to launch credit on UPI as a service, just a month after RBI’s big move, before tying up with Axis Bank.

Dedicated offerings targeted at niche users and specific use cases – Paycrunch (college students), FamApp (teens, students, GenZ and millennials), tvam (health and wellness), Scapia (travellers) – seems to be a trend waiting to pick up.

Lending to sunrise sectors such as electric vehicles and solar rooftops would rise. Add corporate loan-like models viz. loan against mutual funds and collateralization of assets, and you had a heady credit environment.

The flipside is that the fast access to credit, supported by UPI’s ease of use, does carry the risk of luring New-to-Credit (NTC) borrowers into a vicious debt trap – one they will not be able to do with, or without. Indian fintechs already have an outsized share in personal loans and exposure to NTC consumers, thanks to their digital distribution channels.

The regulator was visionary and proactive in warning lenders about their rising unsecured loans portfolios. As the scale of the disruption plays, regulatory guardrails are expected to follow.

Unbridled optimism and euphoria have to be mixed with caution and patience.

Winning the Credit Game at Lightning Speed

UPI has blazed from 100K monthly transactions in October 2016 to 10 Bn by August 2023.

NPCI recently set itself an audacious goal of 2Bn daily transactions by 2030. The path could be the ramp on which the next lending phase builds.

Sachetization of credit is imperative for India’s micro-transaction market at the bottom of the pyramid. UPI 123PAY – vernacular and voice-enabled for feature phones – and UPI Lite – for offline, small-value transactions up to Rs. 200 would take credit deeper and wider into Bharat.

To the deserving user in the appropriate form, credit begets commerce, which over time begets more credit, leading to more commerce and so on. Imagine the small farmer, the daily wage worker and the humble cart puller eased out of their hand-to-mouth existence, empowered with bite-sized loans.

On the national scale, the fledgling ONDC, with its promise of democratizing participation in commerce, is expected to give a fillip to credit offerings tailored to hyperlocal businesses.

The regulators prefer to create the playground and define the rules for the players to take over. Or, at times, allowing the players to set them, acknowledging the strategic importance and the common interests. Like the UPI and the ONDC, the Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN) and the Unified Health Interface (UHI) follow this proven template.

As players explore, pivot, compete and thrive, the game gets much richer. Lending, as it turns out, is the game’s cup of glory. We seldom come across “cutting-edge” business models which are profitable from the get-go, where a 12% return does not sound incredulous, and demand is not a constraint.

At the recently-held Global Fintech Fest, which saw ~300 investors initiate deals worth over $2 billion, nine of every ten pitches had a thesis built around lending.

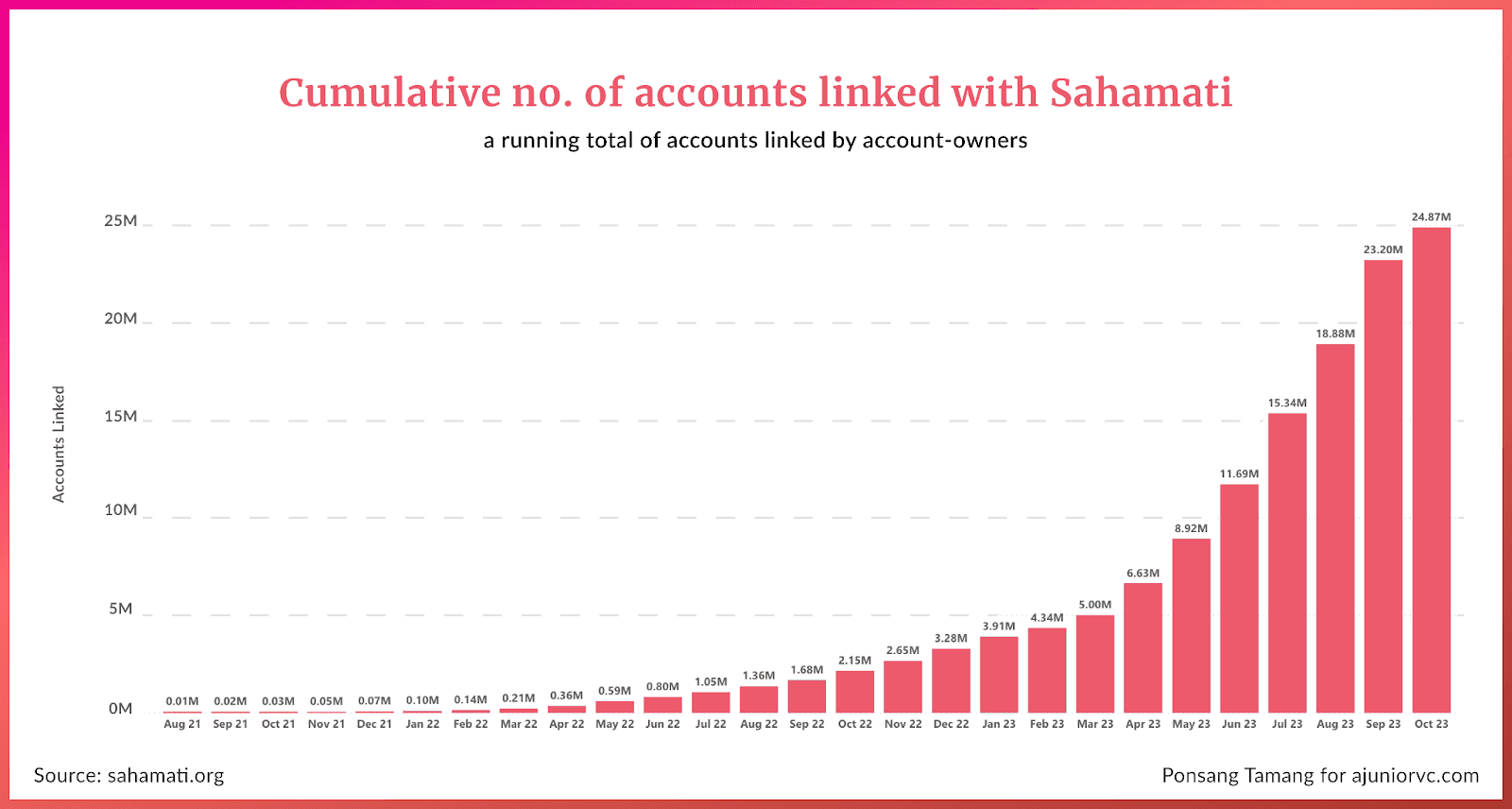

In line with the early growth of UPI, accounts linked to the new revolutionary Account Aggregator framework have quietly exploded. This growth augurs well for the credit ecosystem, bringing more data and information into the mix.

An enormous digital revolution is underway in credit.

Over millennia, lending has fundamentally remained the same at the core. An entity gives money to another. In return, it gets interest.

But what has evolved dramatically is the speed, cost, information, size and access. India is beginning to be at the forefront of this multi-pronged push.

Imagine getting a 100 Rupees loan for a few weeks with a push of a button. That is the hallmark of incredible speed, low cost, full information, bite-size and widespread access.

The framework of credit on UPI, account aggregators and OCEN will combine to make this possible. With a benevolent regulator that is tech-savvy, India looks poised to lend. As fintechs move fast, big entities are becoming more technical to win.

The fast-growing $1Tn lending goldmine is there for the winners.

Writing: Keshav, Mazin, Nilesh, Nikhil, Parth, Rajiv and Aviral Design: Ponsang and Stable Diffusion