Feb 4, 2024

Can India’s 70-Year Struggle Manifest a $1T Manufacturing Powerhouse?

Aggregator

B2B

Manufacturing

Last fortnight, Indian manufacturing reached a 4-month PMI high, as it completed a strong year of manufacturing resurgence across industries

Igniting Innovation

Manufacturing in India has a long and diverse history that dates back to ancient times.

The country has been known for its craftsmanship and industrial activities for centuries. The pre-British period of the Indian economy was primarily agrarian.

A vast part of the subcontinent had self-sufficient villages. Village-level artisans were able to provide for local needs. However, due to geographic factors during that period, they had limited market access.

However urban centres (places of pilgrimage, administrative places, and trade towns) had high levels of economic activity. While these centres primarily met the local market's needs, a significant portion of this production was exported.

Local producers produced textiles and utility-oriented handicrafts. In addition, Indian ornaments, jewellery, brass works, ivory work, and several other notable products gained prominence and achieved significant admiration worldwide.

As the Mughal Empire started declining, the political prominence of the East India Company grew. British rule of India coincided with the Industrial Revolution, which brought about new manufacturing processes and mass production of goods.

Raw materials were required in bulk, and market access for the finished produce had to be enabled. The British thus exploited the Indian subcontinent for raw materials while dumping finished goods on India’s shores. Locally produced goods and their manufacturers started to lose their business.

India’s manufacturing capabilities were waning, the first significant secular decline in Indian production capabilities.

The British monarchy also brought mass production units into the country, further aggravating local manufacturers' situation. This period was not suitable for local industries as they became victims of unfair market situations, destroying any future growth or evolutionary prospects of these industries.

Despite these challenges, green shoots in manufacturing were led mainly by ambitious people fighting for Indian pride.

C. N. Devan pioneered this effort in Bombay when he developed the first cotton mill in 1854. Subsequently, new mills were opened all over India.

In other sectors, successful attempts were made by Prince Dwarka Nath Tagore, Sir J. R. Tata, R. N. Mookherjee, L. R. Kirloskar, and Chettiars of Madras in manufacturing industries.

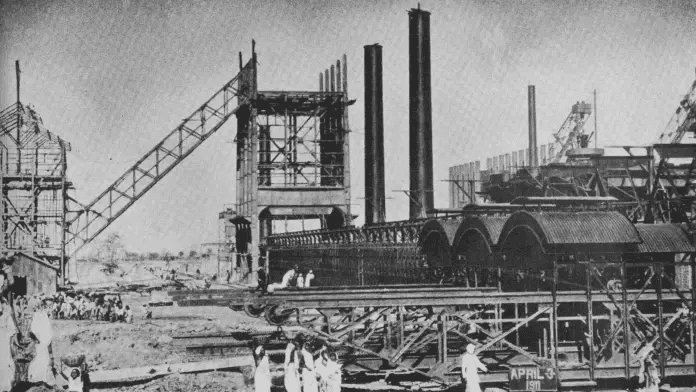

Notably, 1907 saw the Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO) incorporation.

Basic industries such as textile, jute, iron & steel, cement, paper, leather, and light chemicals made considerable progress, partly boosted by the exigencies of the Second World War.

The nation keenly awaited its tryst with destiny.

To redeem its pledge and fulfil the aspirations of 34 crore Indians, manufacturing had to play a substantial role.

Red Tape Roadblocks

At midnight on August 15, 1947, as the world slept, India awoke to life and freedom.

Realising that a strong manufacturing sector was indispensable for economic progress and national security, Independent India chose the path of planned self-reliant development with manufacturing as the main growth engine.

It had a long way to go, given that large-scale industry accounted for only 7% of the national income.

In line with its socialist ideals, the Central Government ensured that state-owned enterprises took a pivotal role.

This was primarily in core sectors like iron & steel, various non-ferrous metals, coal and petroleum-based industries, fertiliser and heavy engineering industries. Industries producing basic and heavy goods were chosen for investment over consumer goods to reduce the country’s reliance on imports of basic and heavy industrial goods.

“To import from abroad is to be slaves of foreign countries,” the first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, once declared.

The production of consumer goods such as clothing, furniture, personal care products, and similar goods was left to small, privately run cottage industry firms. These firms had the added advantage of being labour-intensive and, therefore, a potential generator of mass employment.

The 10-year period from 1950-51 to 1960-61 witnessed considerable growth in manufacturing. Several measures were taken for the development of existing units and the opening up of new ones, which included an increase in efficiency, the removal of obstacles to growth and the initiation of fair competition.

Development was spectacular in the iron and steel industry among the different sectors. Apart from thoroughly overhauling and modernising three pre-existing steel plants, three more steel plants under the public sector were added to the fray.

During 11 years from 1950-51, industrial production increased at a rate of 7 per cent per annum and an enhanced rate of 9 per cent in successive 4 years from 1961.

The domestic manufacturing sector evolved from an industrial base in the 1950s and early 1960s to a licensing Raj between 1965 and 1980.

With License Raj came crony capitalism, and this put the brakes on India’s manufacturing ambitions. Growth became sluggish, reducing to 5.3% in 1965-66. Coupled with License Raj, it forced several large multinationals to leave the country, further hampered India’s technological growth in manufacturing.

The 1960s were the real test for a young India, a period of slowness after an exceptional golden run.

After independence, wars, poverty, illiteracy, and other serious problems were ailing the country. In 1965, the Green Revolution was initiated to combat India’s food crisis, and farmers were given high yielding seeds to produce wheat and essential crops for the masses.

Wielding immense power due to the license raj system, inefficient and ill-equipped government bureaucrats ensured domestic manufacturing suffered through the 70s.

The scale of their inefficiency was amply evident, with two huge examples

Built in the 1970s, the Haldia Fertilizer Plant was a white elephant: employing 1,500 people for 21 years without producing fertilizer, while scooters, the middle-class dream, had an 8-year waiting list.

Our manufacturing sector was hurting and in urgent need of change.

The 1980s marked the shift towards liberalisation, and the 1991 reforms dismantled barriers like industrial licensing and reduced import tariffs.

Industry opened up following economic liberalisation in the 1990s which brought international competition to the country.

Barrier Breakdown

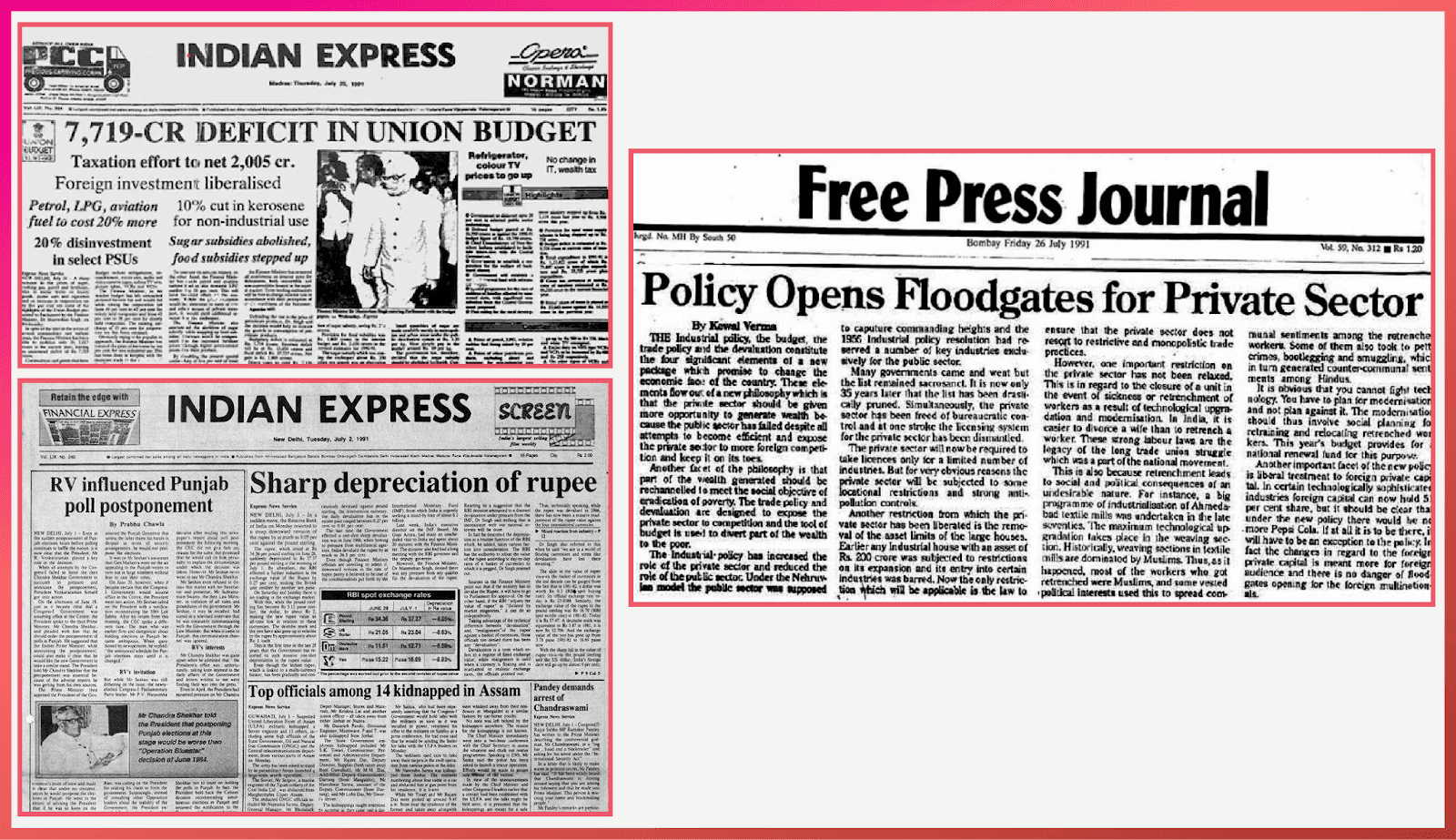

1991 was a pivotal moment for India.

A spate of adverse events had been triggered, starting with the Gulf War-induced inflation of oil prices and India’s import bill, culminating into a balance of payment crisis.

Foreign exchange reserves, at ~$600mn, were barely enough to cover three weeks of essential imports. The current account deficit had reached a peak of 3% of GDP, and short-term external borrowing accounted for an astronomical 380%.

But something good was to come out of this mess.

The situation spurred a series of reforms, broadly along the themes of de-regulating the industry, opening up the economy to external investments and doing away with restrictions

After the decades of License Raj, It seemed like the manufacturing sector’s time had finally come.

Till the 1990s, manufacturing had been overshadowed by services and agriculture in terms of its contribution to the GDP. This was an anomaly.

Traditional economic development models posited a transition from agriculture to manufacturing, and finally the services sector as the dominant drivers of economic growth.

China, with manufacturing accounting for more than 40% of its GDP, was a textbook case.

Immediately after the reforms, the manufacturing sector, growing at its highest-ever annual growth rate of almost 8% from 1992 to 1997, with its gross fixed capital development (an indicator of investments in fixed assets like factories etc.) increasing by almost 1.5x in this time frame.

However, the upward trend was short-lived. After 1997, growth stalled and fell below 5% due to a mix of external and internal factors.

External factors included the Asian crisis of 1997-98, the economic sanctions imposed following the 1998 nuclear test, the rising dominance of Chinese exports, and the global economic slowdown of 2000.

Internally, the boom of the previous years had built up a significant overcapacity, which faced falling inflation, an indicator of falling demand, and a rise in real interest rates, which made investments more expensive.

Moreover, the impetus of the reforms had faded considerably.

This was perhaps most reflected in the fact that despite rampant de-regularization, restrictive labour laws were never loosened – which perhaps became one of the biggest roadblocks towards fully realizing India’s advantage of a massive, low-cost labour force for the manufacturing sector in India.

But where manufacturing failed to fulfil its potential, the services sector shone, led by the booming IT and software industries.

A large English-speaking, technically skilled talent pool and an opening economy encouraged MNCs such as IBM, General Electric and Nortel to set up offshore development centres.

Homegrown firms like Infosys, TCS and Wipro were already testing global waters. And then came the Y2K crisis – a litmus test for India’s ability to export IT solutions – which the country passed with flying colours.

By 2000, the Indian industry had grown 50x in 10 years to reach USD 5 billion in revenue. IT was living the dream that manufacturing could have.

As Indian IT grew, a once-in-a-epoch giant took shape on India’s borders.

World Made in China

China took up the spot as the manufacturing hub of the world.

Chinese manufacturing grew so fast that it went from $360B in 1990 to an astonishing $1.2T in 2000, setting it up for new vertical growth. Chinese manufacturing as a share of global exports grew from 3% to almost 10%.

As China appeared to suck all economic oxygen, Indian manufacturing still had a strong role to play.

Driven by sectors like metals, petroleum, electrical machinery, automotive and pharmaceutical, manufacturing was back to enjoying over 7% annual growth rate during this decade.

Metals and petroleum products had long enjoyed strong government support through multiple PSUs and significant private sector interest.

Giants like Reliance and Tata dominated. Infact, the acquisitions of international metal companies, like UK-based Corus by Tata Steel in 2007 and US-based Novelis in 2008 by Hindalco Industries, were representative of the surge of these sectors in India.

In parallel, Reliance had marked the beginning of this decade by commissioning the world’s largest petrochemicals refinery in Jamnagar, entering the recently liberalised telecommunications space and becoming the first Indian private company listed on the Fortune Global 500 list.

However, the automotive and pharmaceutical sectors boomed during this decade.

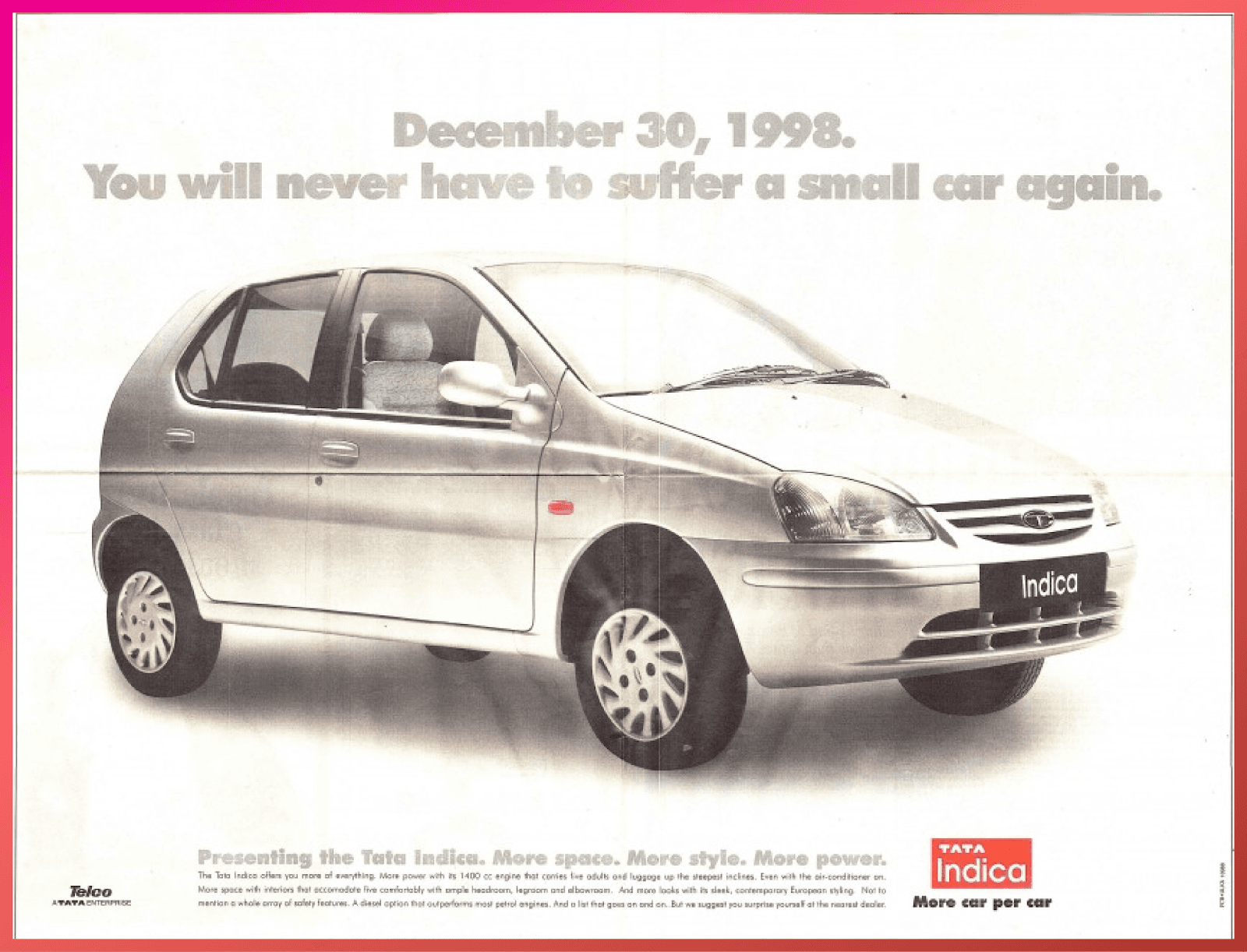

The automotive sector had transformed, from the days of the License Raj.

There was a long wait list for consumers to get their hands on the few models that roamed Indian streets. At the turn of the century, 12 automotive companies had already established a manufacturing base in India.

Several pivotal moments marked this journey.

Tata Motors launched the first indigenously developed Indica car in 1998. This was followed by M&M launching Scorpio as India's first indigenously designed SUV. The Auto Policy 2002 allowed foreign companies to set up fully owned subsidiaries in India, further propelling the sector’s growth.

The luxury market too opened up soon after, with Tata Motors signing a joint venture agreement with Daimler-Benz to manufacture the coveted Mercedes-Benz cars in India.

Global automakers such as Volkswagen, Nissan, Hyundai, and Toyota started using their manufacturing setups in India to serve global markets, establishing the country’s presence in global value chains and significantly contributing ~$4.5Bn to its export base.

Passenger vehicle sales grew almost double the GDP growth rate at over 15% during this decade. Global acquisitions were not limited to metal, with Tata Motors acquiring Jaguar-Land Rover in 2008.

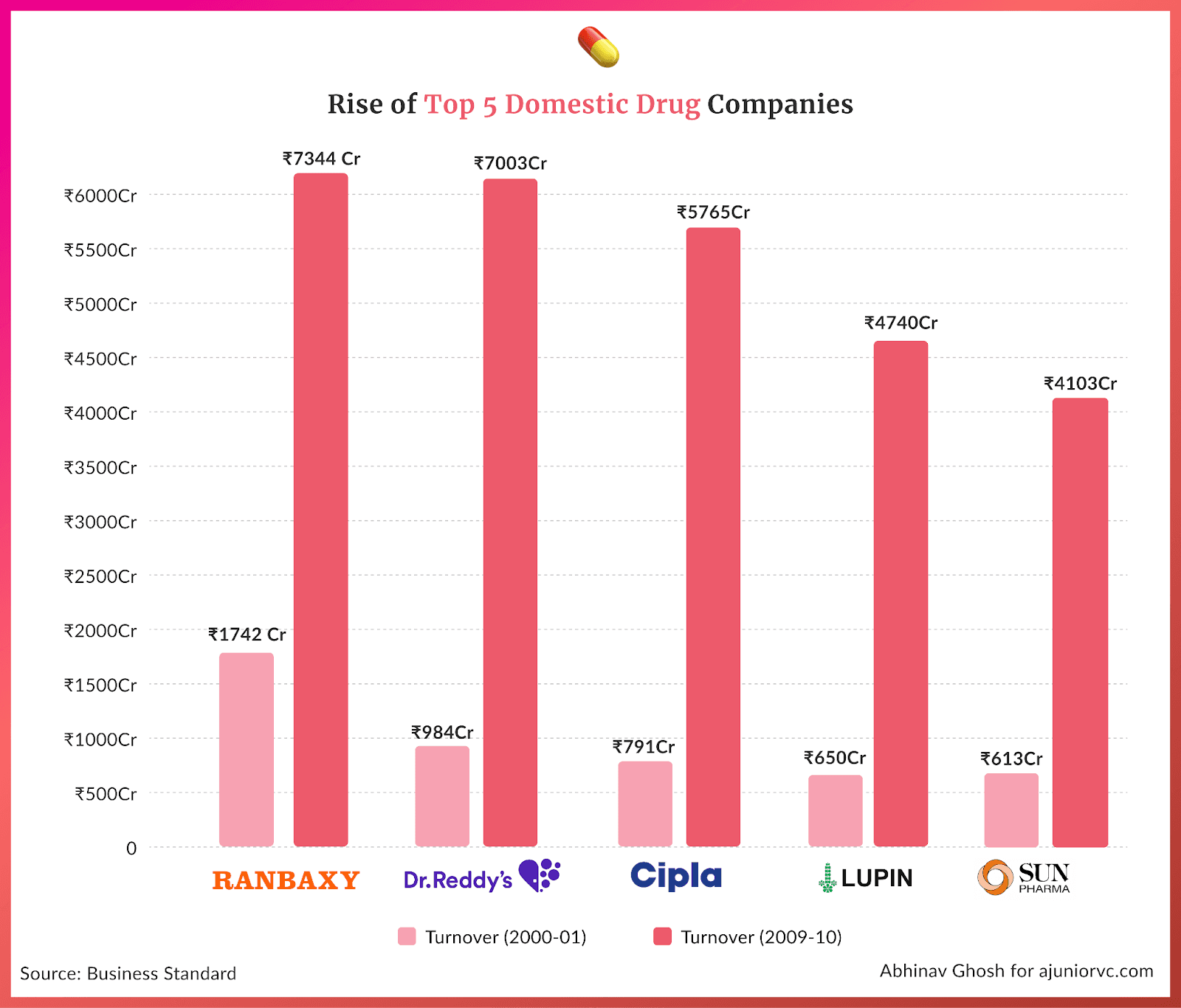

As auto boomed, the big surprise was the pharmaceutical industry.

Between 2000 and 2005, the sector experienced an annual growth rate of 9%, which made it the fourth-largest pharmaceutical industry in the world by volume, accounting for 13% of the global market by volume. Exports grew by a staggering 30 per cent during this period.

The sector has strong price competitiveness, given the low labour and manufacturing cost. Expertise in developing high-quality generic drugs by ‘reverse-engineering’ patented drugs exacerbated the sector’s price competitiveness and yielded strong formulation capabilities.

The next five years saw the pharmaceutical market’s growth rates take off to ~13 per cent per annum, setting the stage for the coming decade.

But the boom times, fueled by easy access to capital, were about to end.

Recession Rebound

The 2008 global recession significantly impacted India's manufacturing sector

Exports immediately declined, and credit conditions tightened. The Indian government promptly responded by reducing central excise duty and ramping up public expenditure, injecting a stimulus worth 2.4% of GDP.

This decisive action helped mitigate the economic slump, propelling the manufacturing sector towards recovery and contributing to a Gross Value Added (GVA) growth from 6.7% in 2008-09 to 8.9% by 2010-11.

Emphasising fiscal responsibility, underscored by enacting the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act, the manufacturing sector's resurgence was buoyed by strong domestic demand.

The automotive industry, in particular, saw an opportunity to expand globally. Tata Motors' strategic acquisition of Jaguar Land Rover for $2.3 billion was aimed at capturing the high-end segments of the global automotive market, leveraging JLR's prestigious brand and economies of scale.

Similarly, Maruti Suzuki and Bajaj Auto tailored their production for South American and African markets, contributing to India's growing automotive exports.

The Automotive Mission Plan and the National Electric Mobility Mission Plan further accelerated the sector's growth, with vehicle production increasing from 15.9 million units in 2010-11 to over 24 million by 2015-16 and exports growing from 2.33 million units to approximately 3.5 million units in the same period.

The pharmaceutical industry also witnessed substantial growth. India became a leading exporter of generic drugs, accounting for 20% of the global volume. The industry's value expanded from $10 billion in 2008 to over $30 billion by 2015.

The government's Startup India initiative 2016 spurred technology startups and innovation, expanding the focus beyond outsourcing to product development, e-commerce, and digital services.

The Make in India initiative launched in 2014 aimed to transform India into a global manufacturing hub. It significantly increased electronics production, including a leap from 2 to 120 mobile phone manufacturing units by 2016.

These strategic interventions and initiatives laid the groundwork for India's manufacturing sector's recovery and growth post-2008, marking a shift towards diversification and technological integration.

This era set the stage for a new upcycle in Indian manufacturing

Bricks to Bits

Targeted policy initiatives significantly shaped India's economic landscape.

The "Make in India" campaign stood out for its pivotal role in fostering manufacturing and attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), with inflows growing at a healthy 15% year over year since its launch.

Jio was launched in 2016.

Reliance Jio revolutionized the telecom sector, dramatically increasing the number of internet users—from 350 million in 2015 to over 600 million by 2020. Jio's aggressive pricing strategy made internet services more affordable, spurring digital transformation across industries.

Similarly, renewable energy underscored the increasing shift towards sustainable development, responding to the growing demand for clean energy sources and contributing significantly to revenue generation and building environmental sustainability.

India's renewable energy capacity saw an impressive surge, growing from 42.85 GW in March 2016 to approximately 87.26 GW by March 2020. Capacity doubled the capacity in just four years and positioning India as a global leader in renewable energy adoption.

The manufacturing sector that witnessed a big boost was chemicals.

This could be attributed to a combination of domestic growth, international demand, and government strategic policy support.

Speciality chemicals led to higher profitability, with companies capitalising on the "China Plus One" strategy and enhanced R&D, driving robust export growth.

The period also saw a surge in technology startups, with India becoming the third-largest startup ecosystem globally. Investments in startups increased, with many beginning to attack the manufacturing potential of the country

OfBusiness is one such story that launched in 2016.

OfBusiness streamlined procurement processes and fostered the growth of SMEs. It made supply chains and raw materials more efficient. With investors sensing the idea's potential, OfBusiness raised $50 million in three years from launch.

The government continued building better infrastructure and policies to improve

India made substantial progress in improving its Ease of Doing Business ranking, from 130 in 2016 to 63 in 2019. FDI to India increased from $55B in FY16 to $74B in FY20. India's exports grew from USD 262B in FY17 to USD 313B in FY20.

By 2020, India solidified its position on the global stage as an emerging leader in manufacturing, ready to leverage its newfound capabilities for future economic prosperity.

But a storm was coming, about to batter anything physical.

Becoming a Plus One

The COVID-19 pandemic swept through India, causing disruptions in almost every industry.

At first, it appeared the COVID pandemic would shock the economy into submission. The economy appeared to be grinding to a halt that wasn’t seen before.

Yet, Indian businesses quickly adapted to the changing landscape, revealing their resilience and capacity for innovation.

India’s pharmaceutical manufacturing dominance would shine through.

Giants like Dr Reddy's, Cipla, Serum Institute and Sun Pharma significantly expanded their production capacities for COVID-19-related medications and vaccines.

This move was essential in addressing domestic and global demand for critical drugs. India's contribution to vaccine manufacturing, including Covaxin and Covishield, played a pivotal role in global vaccination efforts, with millions of doses exported to various countries.

Companies like Maruti Suzuki, Mahindra & Mahindra, and Tata Motors shifted their focus to produce ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPE). Tech companies, such as Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) and Larsen & Toubro (L&T), ventured into producing critical medical devices like oxygen concentrators.

This showed the world that India was as good as anyone. The manufacturing disruptions and impact on supply chains in China made India even more attractive.

Post-COVID, the world realized that moving away from China was imperative. The biggest China bull, Apple, began rapidly ramping up iPhone production in India.

The "China + 1" policy, aimed at diversifying supply chains away from over-reliance on China, saw India emerge as a favourable destination for manufacturing and investment.

2020, 2021 and 2022 marked the best three years of FDI inflows.

Zetwerk capitalised on this rapid, once-in-a-lifetime shift. The budding startup provided manufacturing services that helped firms transition to new suppliers almost overnight. The upstart would hit an astonishing 4,900 Crore of revenue in 2022, growing almost 2x every year.

Startups like Ather Energy in electric vehicles and Boat in consumer electronics demonstrated remarkable adaptability, as manufacturing moved home. In space and satellite manufacturing, startups like Agnikul Cosmos and Pixxel showed innovation.

All the growth was supported by deep investment in infrastructure.

India's national highway network expanded significantly, with a 59% increase in the total length of national highways in the 10 years leading up to 2022. The expansion positioned India as the world's second-largest road network after the USA.

The introduction of FASTag has notably improved toll collection efficiencies, reducing waiting times at toll plazas from 734 seconds in 2014 to 47 seconds in 2023.

These infrastructure improvements proved to be further unlocks for manufacturing.

The cargo handling capacity of India's significant ports substantially increased, reaching 1617.39 Million Tonnes Per Annum (MTPA) as of March 2023. India was targeting a nearly 300% increase in port handling capacity by 2047, aiming to raise the country's total port capacity from 2,600 MTPA to more than 10,000 MTPA.

India's manufacturing focus, infrastructure boost, and tech surge positioned it to become a global export giant, reshaping the international trade landscape.

India was finally getting an opportunity to wrest the initiative from China.

Power Play

By 2022, India was emerging as a potential manufacturing powerhouse.

With strength established in chemicals, pharmaceuticals, automotive and textiles, India had reasons to succeed.

India possessed inherent strengths in these sectors over its US and European peers. A sizable, trainable workforce, mineral and raw material availability, and proximity to key markets, including the domestic market, helped.

A new shoot of growth that built on these capabilities was electronics.

Manufacturers like Samsung, Wistron, and Foxconn shifted production to India because of strong manufacturing and R&D capabilities, a growing supplier base, and strong policy support.

India soon became the 3rd largest exporter and 2nd largest manufacturer of mobile devices, having ~10% market share behind Vietnam and China.

The country moved beyond assembling and is into precision manufacturing in categories like mobile camera lens case making, and prefab units, among others.

Due to these developments, manufacturing exports have seen tremendous growth of 15% CAGR over 2022 and 2023. They were growing between 5% and 10% during pre-COVID and reached $418B in FY22.

In addition to key manufacturing sectors, new-age sectors such as renewable energy, drone manufacturing, defence, and space tech are also propelling India’s manufacturing sector growth.

India has been the 4th largest country worldwide to add renewable capacity over the past decade. India aspires to become the global hub for drone technology by 2030

In spacetech, the successful landing of the indigenously manufactured Chandrayan, achieved at a frugal cost, stands as a testament to India's prowess on the global stage, particularly in emerging sectors.

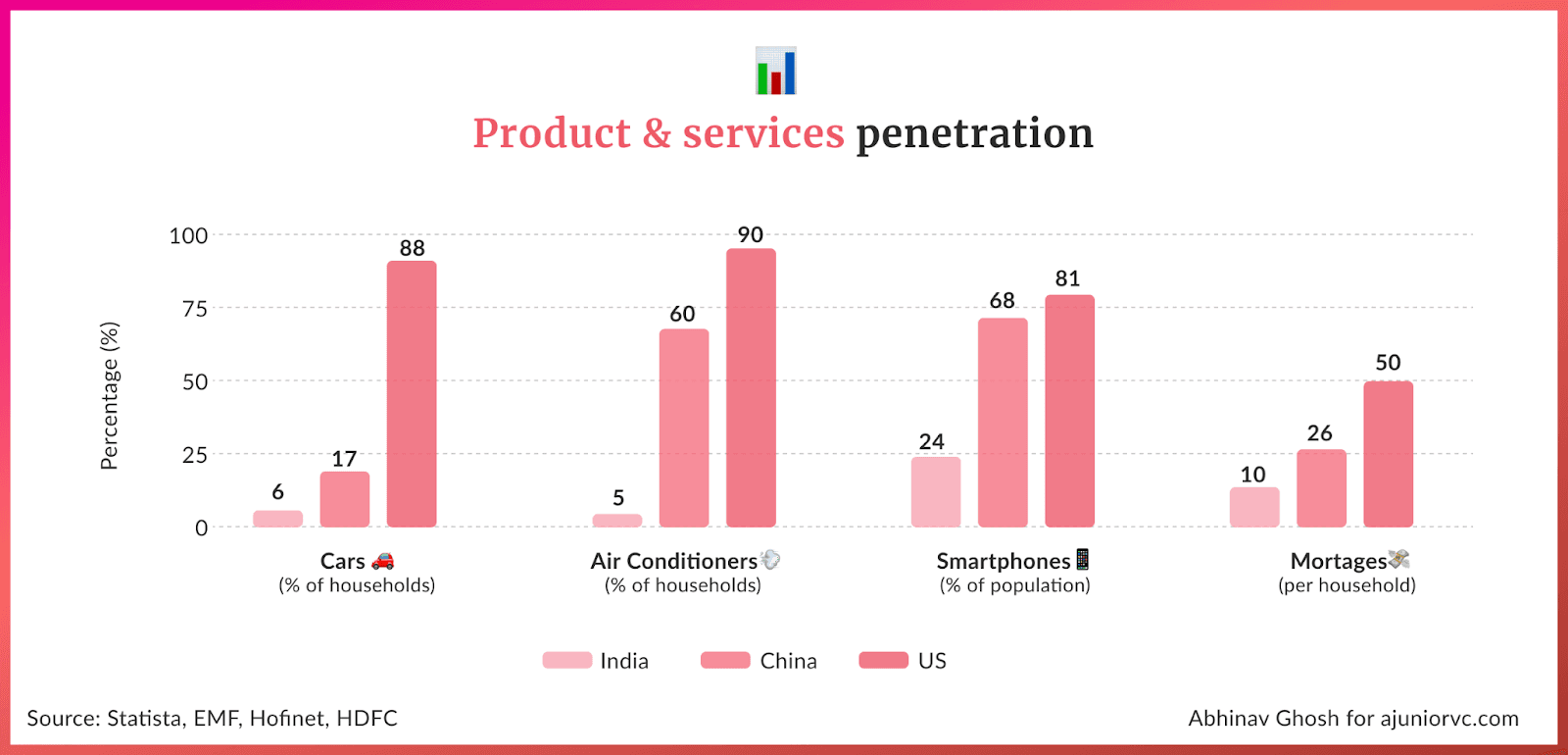

Yet India is at a sub-optimal scale in many sectors compared to giants like China and Taiwan.

For example, in solar module manufacturing, India would have an installed capacity of 65-70 GW by 2027. In contrast, Longi Solar, one of China’s leading players, has an installed capacity of 85 GW in 2022, higher than India's by 2027. The situation is similar in semiconductors and lithium-ion batteries.

Besides scale, India’s domestic manufacturing costs, such as power and logistics, are also higher. Notwithstanding power reforms, India’s industrial power cost is almost 2x of China’s power cost and logistic cost at 14% is significantly higher than its peers.

To make India globally competitive, the government has taken a variety of initiatives such as Make in India, Bharatmala Project, Start-up India, Faster Adoption & Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles (FAME), Atmanirbhar Bharat, Free Trade Agreements, etc., to address the barriers that hamper India.

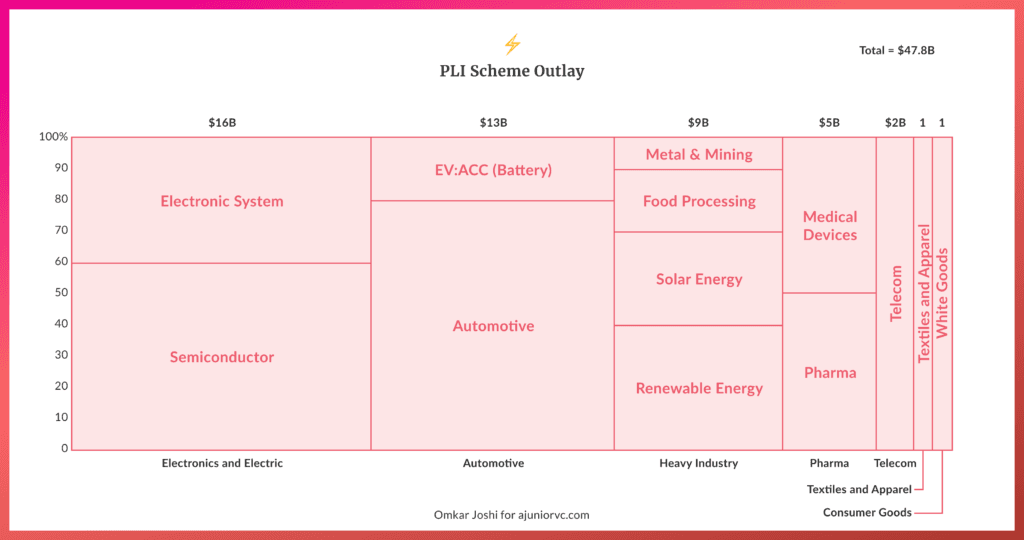

PLI schemes were another effort in this direction. The Indian government developed a scheme with an outlay of 47B to attract large investments across 15 sectors, driving domestic growth and manufacturing-led exports.

India’s capex cycle is expected to fast-track after post-pandemic economic growth and high-capacity utilisation, which will help cater to the increased demand. The Indian government had budgeted a 35% year-over-year (YOY) increase in capex for FY23 to ~ $100 billion.

As it entered 2023, it looked like the manufacturing rollercoaster was looking up.

Forging a Trillion Dollar Future

India aims to increase the manufacturing sector's share of GDP to 25% by 2030 from its current base of 17%.

From Make in India 2.0's focus on 24 key sub-sectors to dedicated textile hubs like Telangana's Mega Textile Park, India's government is creating a fertile ground for manufacturing.

Public-private partnerships like the Chennai-Singapore Industrial Park are streamlining processes, while skilling initiatives like Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana are training millions in areas like robotics and additive manufacturing, ensuring a future-ready workforce.

With a large Rs. 9,000 crore Polycarbonate plant in Gujarat to Apple's growing iPhone production, India's manufacturing muscles are now flexing. The giant plant promises to solidify India's position on the global chemical map, while Apple's 25% iPhone production target by 2025 attracts investments and boosts exports.

India is also taking a crucial step towards self-reliance in semiconductors with its first indigenously built fabrication unit.

These giants aren't standing alone.

Mega infrastructure projects like Bharatmala and Gati Shakti are bridging the gap with seamless connectivity, while dedicated industrial corridors like Delhi-Mumbai and Amritsar-Kolkata nurture specific industries like automobiles and textiles. Skill India Mission 2.0 equips millions with industry-relevant skills to fuel this ambitious engine, and Startup India Vision 2024 fosters homegrown manufacturing solutions.

India also plans to become a net exporter of solar panels by 2025.

This multi-pronged approach aims to propel India onto the global manufacturing map, making it a go-to destination for high-quality, competitively-priced goods.

Samsung recently announced that it will manufacture laptops in India. It already manufactures feature phones, smartphones, wearables, and tablets in India, and with the laptops, it will complete its entire range of products.

Under the modified production-linked incentive scheme for IT hardware, the government has already approved the applications of 27 companies (like Dell, HP, Lenovo, and Foxconn) who will manufacture laptops, servers, and personal computers and collectively invest Rs 3,000 crore.

To become globally competitive, India needs also to trade freely.

The Indian government has been proactive in its trade relations engagement with important trading partners globally and is currently negotiating a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with 16 foreign entities.

This is the highest number of negotiations compared with the alternative manufacturing destinations. When these negotiations are closed and FTA is signed, India will likely be the second most connected trade partner globally, after Singapore, among comparable countries

The government of India has set a goal of becoming a 'developed country' by 2047- an ambitious goal by all measures. By this point, India will also be the third-largest economy in the world.

Glancing at all the large economies globally, manufacturing has been a key driver of their growth. In India, the manufacturing sector's contribution to the country’s GDP has remained relatively low for an extended period, hovering around 15-16%.

The significant push and focus on all fronts is pushing the Indian manufacturing opportunity. From ~$600B today, if it goes to even 20% by 2030 when India is expected to reach $7Tn, it is nearly doubling to $1.2T.

From decades in wilderness and false starts, India’s 70 year manufacturing struggle could finally yield a huge win.

Writing: Ajeet, Parth, Ritika, Shreyas, Varun and Aviral Design: Omkar, Abhinav and Stability