Dec 10, 2023

Can 9,000 Cr PhysicsWallah Counter EdTech's Entropy?

Profile

Education

Brand

B2C

Series B-D

Last fortnight, PhysicsWallah reported clocking 780 Cr of revenue while winning a disruptors award for reimagining EdTech.

Uncertainty Principle

1991 was a tough year for India as it plunged into an economic crisis.

In the same year, Alakh Pandey was born in Prayagraj, erstwhile Allahabad. His father was a contractor involved in construction activities such as building roads. Alakh’s mother, an asthma patient, was a teacher who had quit her job to raise Alakh and his sister.

When Alakh was in the third standard, his father lost his job, plunging his family into financial hardships. To meet household expenses, the father decided to sell half of the house they were in. Within three years, the entire house was sold. The family of four moved to a single-room dwelling in a slum.

It was 2004. Alakh was in the sixth standard.

Despite the troubles, Alakh was never forced to compromise on his education. Loans from friends and extended family kept his studies afloat. Financial constraints notwithstanding, Alakh’s father ensured that his upbringing never lacked a healthy dose of ethics. That set the moral foundation in Alakh, which got engrained as he started and scaled PhysicsWallah.

Expectedly, the founder had a rough upbringing devoid of comfort and middle-class luxury. Such an arduous childhood taught Alakh the importance of money and being frugal, a quality he again carried with him as he built PW.

He realised quickly that he needed to step up to earn and support his family. Out of desperation, he became a private tutor in the 8th standard.

Till then, Alakh was an average student with a weakness in Maths. The economic jolt made him sit upright and take his education seriously. He scored 93% in his Class 10th exams.

He decided to pursue teaching in Class 11. His youthful passion was channelled into his love for this profession. The love and appreciation from his students gave him so much fulfilment that in 2006, he vowed in his diary that he would be the biggest physics teacher in India by 2016.

Alakh joined the same coaching institute as a teacher for 9th grade, where he was taking tuition for 11th grade. As his parents got to know about it, his nascent career at the coaching institute came to an abrupt end.

But Alakh was not perturbed. He continued his coaching classes elsewhere. He wanted to get into the IITs since education in India remains a ladder for upward mobility.

He could not crack it, so he joined Harcourt Butler to pursue engineering.

Hello Baccho!

Three years into his undergraduate studies, Alakh decided to drop out of college.

The state of education completely disillusioned him. In 2014, he returned to Prayagraj and took up a teaching role at one of the coaching institutes.

Soon, his zeal to become the best teacher in the country made him a highly sought-after educator at the coaching institute. He saved almost 70% of the INR 1 lakh monthly salary that he drew.

In parallel, he started a YouTube channel where he would upload videos of the lectures that he would prepare for the day at his offline coaching. YouTube wasn’t a big deal then, a nascent platform that had started growing in India.

The videos were recorded at night, at the same one-room dwelling. That room had no fans nor proper lights and housed his family.

The lectures were recorded on a smartphone, kept balanced precariously on a pile of books.

Alakh looked at YouTube as his full-time teaching medium in 2016. BYJU’s had been around for five years and had become sizeable by then. It was selling tablets loaded with content to K12 students. India had yet to see YouTube as a medium of education. Unacademy and Vedantu had just started.

To stand apart in the crowd, Alakh decided to work hard on average students and turn them into toppers, a feat that was much harder to achieve. Finding good teachers in Tier II and Tier III cities was difficult. He decided to bring himself down to the level of the students and elevate them to greater heights.

His YouTube videos started gaining momentum. All this engagement on his channel came organically, from word of mouth, with zero marketing dollars spent.

As he kept touching higher peaks, his lifestyle did not change. He started upgrading his teaching equipment so that his created content would be higher quality. That’s all where he splurged.

A new edtech was shaping up.

YouTube Sonic Boom

Alakh’s early days on YouTube were a classic case of entrepreneurial pluck and perseverance, aided by lucky breaks.

His business references and inspiration sources remained unknown. However, the budding showman’s commitment to doing things that could not scale would have made Paul Graham nod in admiration.

He went to great lengths to delight his users and create an experience that made them return.

In 2015, YouTube had few content creators. While Unacademy and Vedantu were trying to break new ground, online tutors leveraging the platform to reach a young audience was a far thought.

Alakh was confident that despite the limitations, he could teach as well as anyone. He would prepare meticulously for each session, barely able to contain his excitement till the lecture started. His setup was a mobile phone hoisted on soap bars and its lens trained on the now-legendary whiteboard.

Deliberately or unwittingly, Alakh turned frugality into a differentiating factor, which allowed him to teach without an agenda to sell. It enabled him to earn unconditional trust that could be monetised credibly years later.

He tried a different voice and accent in every video to hold students’ attention. He tried combining his earnestness and forthcoming demeanour with ample folksy humour to keep the proceedings memorable.

But the algorithm then was as uncompromising as it is today. Alakh’s initial videos flopped, and only a while later, his channel bore even a distant semblance of the well-oiled machinery it was to become.

He then started running advertisements on his YouTube videos, much to his students’ resistance. Needing it to support himself, with his love for logic and reasoning, Alakh was swift in making them realise the merit of his decision.

The Jio revolution took everyone by storm in September 2016 and irreversibly changed how Indians consumed data.

For Alakh, who had started with a kitty of INR 10 lakh from his previous teaching stints, earning INR 8,000 monthly from ad revenue was encouraging. A year later, the amount jumped to INR 14,000 per month.

He diligently used the proceeds to enhance production value and platform features and expanded his team of educators.

The broader landscape was about to change forever. Coaching and tuition were to leave people’s lexicon. Edtech was to become the new buzzword.

The time was ripe for the industry to graduate to the next level and catch the attention of VCs.

EdTech Electromagnetism

2016 was characterised by robust edtech growth.

Unacademy, BYJUs, Vedantu, Toppr all broke into the scene at different speeds and stages. Some were starting, some scaling.

The competitive entrance test prep market was at the core of this educational uprising. Many exams like IAS, IIT JEE, NEET, MBA, and Law entrance tests form the battlegrounds for students.

More than 30 million students appear for these competitive exams each year. Their single-minded focus is to conquer the tests and claim their place in the academic halls of excellence.

The primary challenge faced by learners, even when educators like Alakh were actively utilising platforms like YouTube to run their channels, was the limited access to high-speed internet. Many learners found it difficult to afford the necessary internet speed on their phones, hindering their ability to benefit from these online educational resources fully.

With Jio, high-speed data was slowly permeating to every nook and cranny of the country. The once-barren digital landscape bloomed into fertile ground for the edtech sector to flourish with rising smartphone penetration, internet access, and students' ambitions to win big.

The market was a staggering US $2 billion (Rs. 15,000 cr). The segment catering to K12 and test preparation commanded a lion's 50-60% share.

In 2017, the edtech sector experienced significant funding, with an average annual increase of 49% in the number of deals and a remarkable 149% surge in total funding, marking it as one of the most booming industries of the year.

PW positioned itself within the edtech landscape as a specialised platform designed to cater to the educational needs of students.

Serving an age group from Grade 8 through college, PW zeroed in on a pivotal juncture in the academic journey, offering targeted assistance in preparing for entrance examinations.

The core service provided by PW was curricular learning with a particular emphasis on test preparation, honing in on the "Getting into college" phase.

However, PW zeroed in on providing tailored physics education for competitive exams. As astute readers would know, playing in a niche and winning it is better than going after everything.

PW tapped into this digital explosion, offering a cost-effective and flexible alternative to traditional coaching.

The channel's strategy was about education and making it accessible, engaging, and effective for every aspirant.

That was the PW mission, a response to the current demand in the Indian educational landscape. Many EdTechs were scaling, but also burning money.

By 2018, what had to be cracked was if it could ever be profitable.

Conservation of CAC

Scaling the test prep education profitably was difficult in India.

Price sensitivity is a key factor in the test prep market. Despite the high perceived value of these services, there is a limit to what most Indian families are willing to spend. The cost of enrolling in coaching centers or subscribing to online test prep platforms was a substantial financial burden.

In response to this price sensitivity, the competition was intense, with many online and offline test prep providers aggressively marketing their services to differentiate themselves and justify their costs.

The rise of online education platforms intensified this trend, as digital marketing became a crucial tool to reach potential students. Providers invested heavily in social media advertising, influencer partnerships, and content marketing to attract students.

In 2019, Unacademy allocated over INR 400 crore to marketing efforts. BYJUs spent an astonishing 2,000 Cr on marketing.

Riding on Alakh’s visibility, PW achieved its growth organically without significant investment in marketing.

Performance outcomes of institutes played a vital role. Those with a high exam success rate were more attractive to new students. Newer institutes with less proven success spent more on marketing, leading to a higher customer acquisition cost and potential financial strain.

This is exactly what was happening in the online edtech space.

Companies in the test-prep space, such as Unacademy, Vedantu and Toppr, were losing money north of Rs. 100 cr. per month. PW chalked up a formula that balanced the books and led to profit.

The secret was a freemium model that turned free YouTube content into a gateway for premium courses.

Free lessons on YouTube acted as the 'hook'. Eager learners got a taste of PW's teaching style. High-quality content kept them coming back for more. The real magic, however, was in the transition, moving from free viewers to paid subscribers.

PW's offerings were attractive to students. They balanced affordability with quality, making top-notch education accessible to all.

Course prices were just a fraction of what peers charged. This allowed PW to go after a larger audience. Some courses were offered for as low as 10,000 INR, while more structured programs were 40,000. While these were higher tickets for the average Indian consumer, they were substantially lower than other edtechs.

The large variable cost in selling a course was marketing spend. Thanks to organic growth fueled by stellar content and word-of-mouth praise, CAC was 0.

PW became the only profitable edtech player in India in 2020.

It could do something special by sticking to the fundamentals—maximising value, minimising cost, and prioritising learning outcomes. They proved that the best price was not always the highest in the education market.

Pandemic Potential

In 2020, when the world hit pause, education didn't.

The pandemic, while a global challenge, unexpectedly catalysed the edtech industry. The digital classroom became the new norm during this period, marking a monumental shift in how we perceive learning.

In the same year, the meeting between Alakh and Prateek Maheshwari was more than just a collaboration. It was a strategic alignment when offline education systems were faltering.

Unlike its competitors, PW continued to go down the path of affordability, ensuring quality education remained within reach for all.

Capitalising on its YouTube channel's success, PW launched its app, offering courses at astonishingly low rates.

The prices ranged from INR 500 to INR 4,500, with an average cost of INR 3,500. This pricing strategy undercut the fees of counterparts like Unacademy and Vedantu and traditional offline coaching classes with an average course price of INR 15,000, making quality education more accessible.

The validation also came in the same year.

By 2021, over 10,000 PW students cracked prestigious exams like NEET and JEE, despite the pandemic's disruptions.

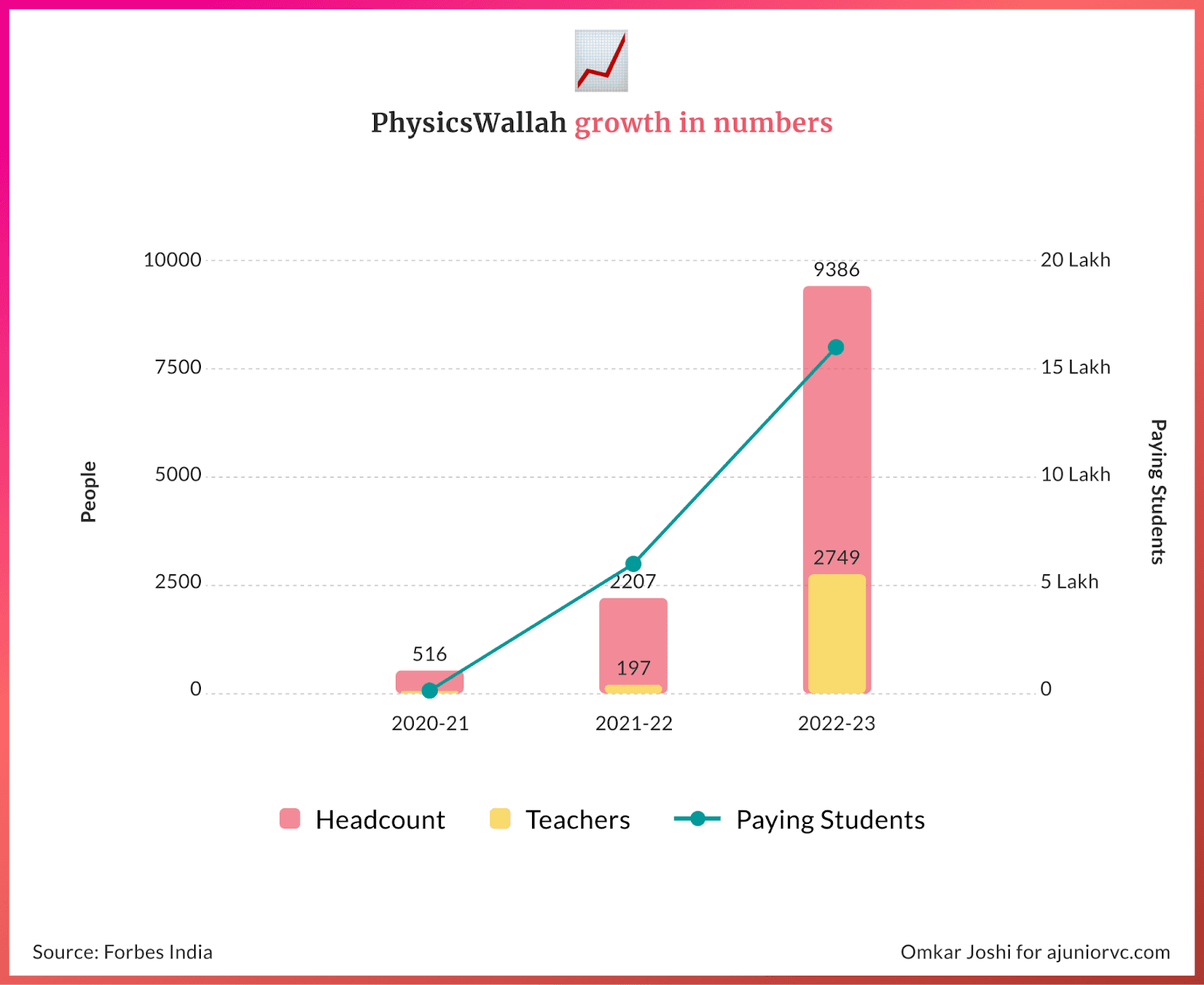

As a result, PW recorded a fourteen-fold increase in net profit in FY22, reaching Rs 98 crore, up from Rs 7 crore in the previous financial year. Operating revenue also saw a nine-fold rise, reaching Rs 234 crore in FY22, compared to Rs 25 crore in FY21. This growth trajectory was not just a fluke but a result of strategic decisions and a focus on innovation.

Understanding the diverse needs of students, PW also introduced features such as a doubt-solving engine, mentorship from industry professionals, scheduled learning, and student polls. Despite the industry's focus towards live learning, PW continued to offer offline recorded classes, aligning better with its target audience's needs.

These features made learning more interactive and helped retain users by providing a more hands-on learning experience.

By 2022, the company had 4 million users on the app and over 10 million subscribers across its YouTube channels.

PW partnered with schools and institutes, leveraging these collaborations for broader access. PW's strategy focused on brand-driven engagement, unlike its peers' field-sales-heavy tactics. This approach emphasised building lasting relationships over aggressive sales tactics.

Alakh's brand was a cornerstone of PW's strategy. His name resonated with trust and quality education. This brand recall was instrumental. It wasn't just about ads, it was about building a relationship based on trust.

PW's journey through these pivotal years wasn't just about weathering a storm but charting a new course in unexplored skies.

PW was poised to enter a different orbit, setting new standards in the edtech sector.

Cosmic Competition

By early 2022, with the pandemic subsiding, and offline classes restarting, the edtech sector was unravelling.

Two major categories shaped this dynamic edtech landscape: new-age tech startups and established offline coaching institutes.

While startups like Unacademy, Vedantu, BYJUs, OnlineTyari,Toppr capitalised on their tech prowess to capture market share and drive down prices in the pandemic, they now had to deal with the resurgence of the offline coaching institutes. Legacy brands like Aakash, FIITJEE, Vidyamandir, and Allen posed formidable competition.

In navigating this tumultuous field, PW had to chart its trajectory like an electron in an electromagnetic field.

Major edtech unicorns, including Unacademy, Vedantu, and BYJUs, struggled to maintain valuations, crumbled under losses, and had to resort to layoffs to stay afloat. Rounds that had valued many as unicorns just a year ago were starting to look on thin ground.

But PW had always been different. It had not raised a single penny.

Surprising everyone, PW raised a maiden institutional round of $100M to emerge as India’s 101st unicorn. Being the country’s only profitable edtech unicorn was the icing on the cake.

While rival edtech startups went for the tier-1 market of English-speaking students from well-off families, PW targeted an audience that valued robust learning over high-end features.

Unlike the hierarchical batch system and a rushed approach to cover the vast portion, PW followed an equally paced course that helped students from even government schools get quality education.

The results spoke for themselves. While PW had a relatively modest daily active user count of 5.5 lakh students, the average session time of 1.5 hours was miles ahead of the competition.

Picking up from Alakh’s early days of personally replying to students’ doubts in YouTube comments, PW’s app stayed user-first. While competitors were in the race to gain market share and sell courses by putting pressure on parents and unscrupulously, PW simply followed their student’s orders.

While competitors boasted of teachers from IITs, PW instead focused on their teaching problem and hired the best person to solve it. Feedback collected in-app and through an unconventional system of QR codes in offline classes allowed PW to hold their teachers accountable and improve their standards.

Alakh announced plans to expand content offerings, open more learning centres, and launch content in 9 languages.

As edtechs laid off employees impacted by the funding winter, PW planned to add up to 150 employees each month. Staying student first and super affordable, PW challenged new-age startups and traditional giants in reach, revenues, and respect with zero marketing costs and in half the time it took others.

Its fundraising came after most of the EdTech ecosystem, but it was now positioned to capitalise.

Destroying Dark Energy

By mid-2022, while students adjusted to the new normal post-Covid lockdowns, Indian edtech faced its moment of truth.

Had it managed to make learning truly remote, or was it just a stopgap necessitated by the pandemic

PW and its peers could not teach students a new habit for all the lessons imparted in the previous three years. The most tangible sign was these upstarts entering the offline business, a space they had originally planned to disrupt.

The first PW Vidyapeeth center opened in Kota in June 2022. As the team soon learned, running a physical classroom was a different ball game involving production hell.

Space constraints meant that the low-price and high-volume online playbook would no longer work. Sessions could not be run as simultaneously as earlier, needing a larger base of trained teachers.

Logistics, technology, ground coverage and unit economics had to function in sync. Add the flavour of Kota’s intense competition and the perennial threat of poaching teachers, and you get a heady mix.

PW went through a trial by fire, at times, visibly so.

A video of a scuffle between its management and students went viral on social media, inviting worry over the brand’s dilution. That was not to be the only distraction.

Three of seven academic directors quit and set up Sankalp Bharat, citing PW’s growth-at-all-costs mindset as the culprit. PW accused them of colluding with rival platform Adda247 in a public spat. A fourth director joined the rival faction later.

The senior functionaries were not just PW’s oldest employees but were also handling its new offline centres.

Bad blood had to be dealt with young blood. Alakh & co. readied a $40M purse for inorganic expansion, planning for diversification and new growth levers.

Over the next 15 months, PW acquired and bought stakes in nine players. Each was profitable and aimed at building optionality for the business’s future.

Despite its travails, the offline operations secured 27,000 admissions in its first year after processing refunds for 5,000. This was driven by a scale of up to 67 centers across 38 cities.

Students and parents were vocal in their preference for offline over online, leaving no doubt about how PW had to deploy its funding proceeds.

The new way of business had contrasting impacts on the top and bottom lines.

PW’s core operations recorded a 3x jump in revenue to close at INR 751 Cr. in FY23. On the other hand, profitability margins were hit as expected, given the teething troubles associated with expanding the offline footprint.

PW had yet again displayed an uncanny knack for survival, much like its talisman.

But in its rapid pursuit to cater everything to everyone, was it committing the same mistakes that the once blue-eyed boy in edtech had done?

Building Business Superconductivity

PW has come a long way. The fact that it has remained in the black for 3 consecutive years is no meant feat, especially in the bloodbath that edtech has been!

PW’s strongest moat continues to be Alakh and his thumbnail-dominating face. The 32-year-old’s messianic persona and cultish following have been built on street-smart tricks, life lessons and witty one-liners mastered over two decades.

His rustic charm and earthy teaching style resulted in free, word-of-mouth publicity for the firm since its early days, saving precious millions in marketing outlay. In hindsight, PW’s low customer acquisition costs make its 0 to 1 journey appear serendipitous and opportunistic.

The journey of 1 to 10 and beyond would be saddled with expectations of exponential growth and mandates a deliberate effort to hedge keyman risk. Alakh, the teacher on a YouTube channel to Alakh, the founder of a large business, is a big risk.

Early efforts in this direction indicate that the firm has learnt from the tale of Byju Raveendran and his eponymous venture.

Prateek Maheshwari, the other co-founder, recently assumed co-chairmanship of the India Edtech Consortium, signalling as much a rise in his stature as PW’s coming-of-age. Recent business moves and new focus areas also exhibit a conscious pattern of stepping out of Alakh’s shadow.

PW has invested INR 120 Cr. into PW Skills, the re-branded iNeuron and has hired former LinkedIn executive Vishwa Mohan to lead its efforts to build job-ready skills. It recently opened the doors to its Institute of Innovation in Bengaluru, offering four-year residential programmes in business management and technology, with placement opportunities.

It has also announced plans to invest INR 500 Cr. in Kerala-based Xylem Learning. While South India is a geography with as much emphasis on higher education as any other, PW cannot rely on Alakh’s inimical appeal to establish its presence there.

Likewise, the acquisition of K-12 edtech Knowledge Planet marks its first international move, which has been the Achilles heel for BYJU and Unacademy, among others.

The flipside of shifting away from Alakh as the centre of gravity is maintaining the company's soul. Educational firms that move away from the teacher-founder must be sensitive to maintaining the firm’s deep connections with its students.

PW enters an interesting situation for an edtech firm.

The next phase of PW's growth will be determined by how seamlessly it can integrate acquisitions into its fold, whether it can retain agility while scaling in size, and how it maintains profitability while pursuing growth.

Coaching centres in India have struggled to scale pan-India. When an institute achieves significance, it becomes prone to fragmentation as teachers branch out or are poached and competition increases.

It is natural selection in its rawest form, perhaps teaching Darwin to students by example rather than the book.

Growing into the 9,000 Cr valuation will need tremendous scale and growth. As edtech remains battered, revenue multiples of 3-5x are par for course.

With an FY24 target of INR 1,900 Cr from core operations and an additional INR 600 Cr. from acquisitions, PW is setting a difficult yet necessary target. Whether it realises its aspirations depends on whether it can master time or as physics defines it, master change.

Starting from a tiny YouTube studio in a small home, the journey of PW has been one that has defied set rules. PW looks set to capitalise on its unique situation to build for the next decade.

Writing: Keshav, Nikhil, Parth, Raj, Sahil and Aviral Design: Chandra and Omkar